Cunningham: What’s Driving Chicago’s School Turnaround Success? Lessons From 30 Years of Ed Reform

Updated Jan. 17

It’s often been said that success has many fathers but failure is an orphan. Consider the Chicago Public Schools.

Declared the “worst schools in the nation” by Education Secretary William Bennett in 1987, Chicago today is the fastest-improving district in the country, according to Stanford professor Sean Reardon, with students gaining a remarkable six years of learning in five years.

Chicago is outperforming districts all across the state, says University of Illinois researcher Paul Zavitkovsky. This is true for the system overall and for subgroups of students, including African Americans, Latinos, and low-income kids.

It’s not just test scores, says Elaine Allensworth of the UChicago Consortium on School Research. Student attendance is up, high schools are offering more rigorous courses, and high school graduation and college enrollment rates are rising.

So what’s driving Chicago’s success?

There is no shortage of theories, from greater school choice and accountability to unsexy stuff like professional development and aligned curriculum. Others credit principal autonomy, demographic shifts, mayoral control, expanded preschool, and better use of data.

To one degree or another, all these conditions exist in Chicago, but educational research rarely shows clear causation between reform and results. Instead, most research merely shows correlation — initiatives followed by outcomes, linked only in theory, with no definitive conclusions about what actually works.

In Chicago’s case, however, there are some clear lessons to be learned from 30 years of reform, especially around strong school leadership, great teaching, data, and transparency.

To understand how Chicago moved from worst to something far better, it helps to know some history.

Labor Unrest, White Flight, and Decentralization

At the time of Bennett’s dire assessment, CPS was widely seen as wasteful, besieged by labor unrest — a school system of last resort. Between 1969 and 1987, CPS endured nine teacher strikes and an exodus of white students, who made up 50 percent of students in the 1960s but account for under 10 percent today.

In 1988, the State of Illinois decentralized power in CPS by authorizing elected Local School Councils for each of the district’s 600 schools, with authority over budgets and principal hiring. By law, the councils included parents, teachers, and community representatives.

The other critical development of this era was the creation of the Consortium on School Research at the University of Chicago in 1990. For 27 years, the consortium has produced independent, high-quality research and data reports that have brought transparency to CPS and fostered a public dialogue based on facts.

As with any reform, the results of decentralization were mixed. A 2006 consortium report on the impact of the councils estimated that a third of the schools adopted meaningful reforms and about 1 in 6 made measurable gains in student achievement.

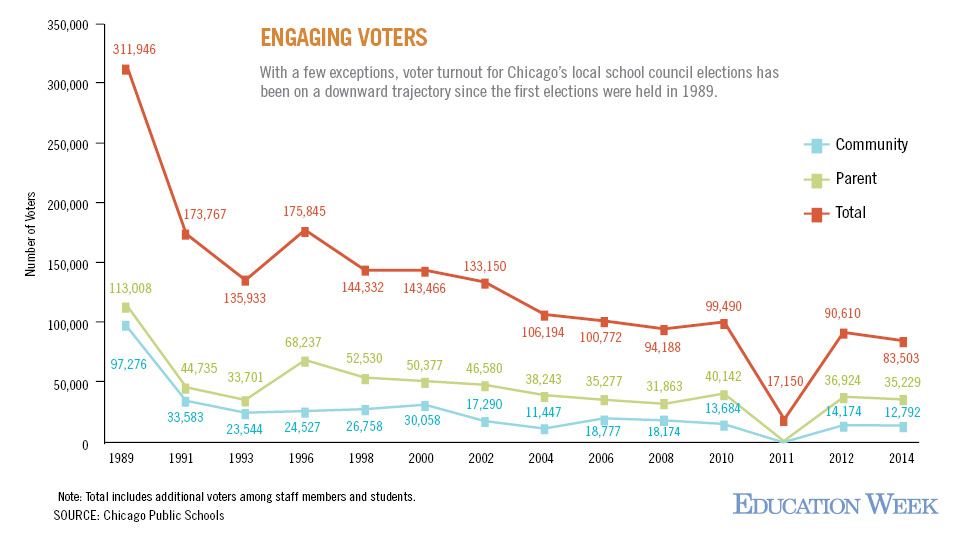

In many other schools, however, there was little progress. Hiring decisions were based more on politics than competency. Over 90 percent of retiring principals were replaced by assistant principals, with little regard for quality. Electoral participation quickly declined.

Labor Peace and Mayoral Control

After the 1987 strike, a 25-year era of labor peace began that continued through Richard Daley’s 22 years as mayor, from 1989 to 2011. Some say CPS bought labor peace with annual salary hikes averaging 3 percent over the past 20 years, outpacing the rate of inflation. On the other hand, generous (some might say fair) bargaining agreements enabled CPS to drive reforms.

The laws of supply and demand also suggest that competitive pay helps boost teacher quality. Today, Chicago has some of the highest-paid teachers in the country, although a Chicago Tribune analysis shows salaries below those in some neighboring suburbs.

Daley’s first political ad in 1989 featured him direct-to-camera talking about big problems in Chicago, including education. At the time, the mayor had little control over schools.

Unlike most of America’s 14,000 school districts, Chicago has never had an elected school board. Before 1995, it was overseen by a 15-member board nominated by a 23-member commission — an overly complex process with little accountability.

With schools stagnating in the early 1990s, pressure grew to reform district governance. In 1995, during a brief period of Republican control of the Illinois legislature, Daley, against the advice of some top advisers who worried that he would be blamed for the district’s shortcomings, gained full control of the district.

He appointed his chief of staff, Gery Chico, as president of the Chicago Board of Education and installed his budget director, Paul Vallas, as CEO. Chico and Vallas slashed bureaucracy, began a school-building program, introduced charters and school choice, and expanded magnet and International Baccalaureate programs.

Ending Social Promotions

The biggest policy decision of the Chico-Vallas era was ending social promotion — the practice of moving kids along each year even if they are not ready. In 1997, 22,000 third-, sixth-, and eighth-graders attended mandatory summer school, and several thousand repeated a grade. Grade retention on this scale had never been done before, and the message was clear: Classroom results matter.

Vallas and Chico also began putting struggling schools on academic probation, which effectively brought them under central office oversight. Among other things, schools on probation no longer selected their own principals.

In 2001, Daley appointed Arne Duncan as CEO. He brought in Barbara Eason-Watkins, a well-regarded school principal, as his chief education officer. She hired over 100 reading specialists and doubled the amount of classroom time devoted to reading.

Duncan increased the number of preschool slots under the leadership of a national early-learning expert, Barbara Bowman. With foundation support, he invested heavily in teacher quality, recruiting from more selective colleges and upping the number of teachers earning the highly regarded National Board Certification credential from just a handful to more than 1,000.

Duncan also bet heavily on principal leadership through a partnership with the University of Illinois at Chicago and began replacing weak school leaders with better ones through early retirements, buyouts, and performance-based personnel shifts. “The school is the unit of change” became the district’s mantra as Duncan extended more autonomy to better-performing schools and more oversight to laggards.

By the mid-2000s, more than half of the district’s principals had less than three years on the job. Today, the principal turnover rate in Chicago is comparable to that of affluent districts across the nation, according to data from the Chicago Public Education Fund, which helps support the principal leadership work.

Closing Low-Performing Schools and Opening New Schools

Duncan’s biggest move was to begin closing schools for low performance, something few districts had done. He started with just three closures in 2002 and continued shuttering up to a dozen each year.

One of the first to close and reopen under new leadership, Dodge Elementary, later hosted an extended visit from then-Sen. Barack Obama in 2005. Three years later, President-elect Obama returned to Dodge to announce Duncan’s nomination as U.S. education secretary, and the experience inspired the administration’s school turnaround program.

While school closings generated a lot of controversy, Duncan and Daley were aggressively opening new charter schools, magnet schools, and traditional public schools. Demand for seats in good schools far exceeded supply, especially among middle-class parents competing for slots in the district’s selective-enrollment high schools. All told, the district closed about 100 schools during the first decade of the new century but opened about 150.

Today, those selective high schools regularly rank among the top schools in the state and the nation. The district claims to have more International Baccalaureate programs than any other district in the country, 36 by one count.

Chicago also has one of the leading charter high school networks in the country. All told, Chicago’s 122 charter schools serve about 60,000 students, roughly 16 percent of the total.

Turmoil at the Top

Since Duncan’s departure in early 2009, seven people have occupied the CEO’s office. Two were appointed by Daley and the next five were appointed by his successor, former congressman and White House official Rahm Emanuel, who was elected in February 2011.

Emanuel’s first CEO, J.C. Brizard, who had worked in New York City and Rochester, New York, served for a little over a year. He was replaced by lifelong educator Barbara Byrd-Bennett, who had led school systems in Cleveland and Detroit. She left after three years in the wake of a contracting scandal that landed her in federal prison.

After a brief interlude under the leadership of lawyer and school board member Jesse Ruiz, Emanuel brought in a seasoned Chicago political pro, Forrest Claypool, to help stabilize finances, and an accomplished principal, Janice Jackson, as chief education officer. Late last year, Claypool stepped down over an ethics issue and Jackson moved up. She is the first local educator to lead the district in decades.

The Emanuel Era: Reforms, Labor Unrest, School Closings

Even before Emanuel was sworn in as mayor, the state was passing a law that would usher in a new era of reforms. It would also trigger an end to 25 years of labor peace.

Senate Bill 7 allowed for a longer school day, streamlined teacher dismissal procedures, and established a stronger link between tenure and student performance. It paved the way for a more robust system of evaluating teachers based in part on student achievement, a key priority of the Obama administration.

SB 7 also raised the percentage of teachers required to support a strike from 50 to 75 percent. In doing so, the law inadvertently made newly elected Chicago Teachers Union president Karen Lewis a national hero.

A charismatic and well-regarded high school chemistry teacher, Lewis ran in 2010 on a vow to fight Daley’s reforms. In newly elected Mayor Emanuel, however, she found her ideal foil — an impatient disruptor with a national reputation in a big hurry to make a mark.

Following the reforms imposed under SB 7, Lewis called for a strike vote in fall 2012 and secured over 90 percent member support. The seven-day strike garnered national headlines and put CPS and City Hall on the defensive.

The strike was an emotional and financial victory for the union and inspired a wave of resistance among teachers unions across the country. Nevertheless, the essential reforms survived in the resulting contract: a longer school day, evaluation based in part on test scores, and layoffs based on performance as well as seniority.

With the strike behind him and a four-year teacher contract in hand, Emanuel shifted his focus to the district’s financial problems, targeting low-enrollment schools. In 2013, the board closed 49 underenrolled schools, shocking the system and further escalating union tensions.

His thinking at the time was that it was better to close the schools all at once and reap maximum savings than to do a few each year. The union pushed back hard, and Lewis even flirted with running for mayor in 2015 until health problems derailed her candidacy. The union-backed candidate, Jesús (Chuy) García, forced Emanuel into a runoff even though García was outspent more than 3 to 1.

In the end, there was little the union could do to stop the school closings, although one community managed to reopen a closed high school with a hunger strike.

Emanuel promised not to close any more schools for five years, though a handful have shuttered due to “zero” enrollment. Meanwhile, to meet parent demand for more options, the district has continued opening new schools, further exacerbating the underenrollment problem.

Financial Problems

Illinois has a long and disreputable record of underfunding schools, which pressures local taxpayers and causes extreme inequity in per-pupil funding levels between wealthy and poor districts. Per-pupil spending in the state varies from as much as $32,000 in some districts to less than $5,000 in others.

With the election of Republican financier Bruce Rauner as governor in 2014, the battle over school funding escalated with an ugly, and some say racist, narrative about “bailing out” Chicago at the expense of the rest of Illinois.

Part of the problem is that Chicago taxpayers fund their own teacher pensions while other Illinois districts are part of the state pension system. With Chicago teacher pension costs skyrocketing, Claypool took extreme measures to keep the district solvent: borrowing at high interest, furloughing employees, cutting school days, and laying off teachers.

Last summer, the state finally raised taxes and passed a new funding formula that promises greater stability in the years ahead. At about $15,000 in per-pupil spending, Chicago is above the national average but below several other big cities like New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C. The pension problem is far from solved, however, and the district’s money woes will continue.

Lay of the Land

Today, Chicago’s school system is radically different from the one Bennett condemned three decades ago. Student enrollment in America’s third-largest district is currently at 371,000, down about 200,000 since the 1970s and down 60,000 just since 2000.

Since 2000, black student enrollment is down by 90,000 and now makes up a little more than a third of the student body, while Latino enrollment is up by almost 30,000 and accounts for nearly half. Despite demographic changes, the percentage of low-income students, defined as qualifying for free and reduced-price lunch, has held steady at around 85 percent over the past three decades, well above the national average of 51 percent.

Despite gaining students a remarkable six years of learning in five years — an impressive rate of improvement — Chicago is far from where it needs to be academically. On both state tests and a national exam administered every two years to random samples of students across America, only a quarter to a third of CPS students are proficient in reading and math.

Similarly, CPS graduation and college enrollment rates are below the national average, but, given the much higher levels of poverty in Chicago compared with the country as a whole, the 30-point gain over the past 20 years is meaningful.

So What’s Driving Chicago’s Progress?

Much of the credit for rising graduation rates goes to the development of a freshmen-on-track metric devised by the consortium and targeted interventions from local organizations like the Network for College Success.

As for Chicago’s overall gains, some attribute them to changing demographics and higher rates of student retention. But Reardon looked at both and concluded that neither explains it. The longer school day began toward the end of the period he studied, 2009–14, so that’s not a big factor either.

Another theory is that this period of time coincided with turnover in the mayor’s office and the CEO slot, as well as labor unrest. With City Hall and the central office distracted, perhaps principals were freed up to innovate.

Still others question whether the claim of “fastest-improving” is justified. Emily Langhorne and David Osborne of the Progressive Policy Institute look at different metrics to argue that New Orleans and D.C. have outgained Chicago, though they acknowledge the validity of Reardon’s research. They attribute much of Chicago’s progress to aggressive replacement of failing schools with stronger schools—most of them charters—and suggest scores have flattened recently because new school creation has slowed down

It may just be that after 30 years of reform and experimentation, Chicago has finally hit a tipping point and a culture of continuous improvement has set in. As one close observer suggested, “Maybe Chicago has finally figured out how to educate poor kids.”

It’s hard to identify the key lever of change because education reforms tend to accumulate rather than replace each other. With a few exceptions (merit pay and small schools), most of Chicago’s reforms from the past 30 years have lasted to one degree or another.

Chicago still has local councils and mayoral control. There is a strong teachers union, and it evaluates educators based in part on student learning. Notably, about 25 percent of Chicago charter school teachers are unionized, compared with about 10 percent nationally.

Chicago has a strong principals association led by an avowed and aggressive opponent of reform, yet the district continues to replace struggling principals based on student performance. The University of Illinois at Chicago principal training program is still in place.

Chicago has lots of magnet and charter schools and has an open enrollment system allowing students to apply to any school in the city. In fact, less than half of CPS students attend their zoned neighborhood schools, forcing schools to compete for students.

And, with Emanuel’s five-year moratorium on school closings expiring this spring, Chicago still has between 100 and 200 underenrolled schools. Like it or not, more school closings seem inevitable, and that’s not all bad.

School closings tend to affect the weakest schools, and research suggests struggling kids do better when they transfer to better schools. Initially, many students were not moving to better schools, but in recent years that has changed.

Among other things, better schools attract better teachers, which is unarguably a key factor in driving success at CPS. Over the years, there has been a consistent commitment to recruiting and supporting principals and teachers, raising standards and adopting better-aligned and more rigorous curricula.

In a 2010 report called “Organizing Schools for Improvement,” the consortium identified five essential characteristics of a successful school: ambitious instruction, collaborative teachers, involved families, supportive environment, and effective leaders. Among these five essentials, the report concluded that effective leaders are most important. Without good school leaders, the other four won’t happen in a consistent, meaningful way, if at all.

Three Big Lessons

If there are any concrete takeaways from the Chicago experience, they are:

First, good data presented honestly and independently really matters. You can’t solve a problem if you can’t see the truth. States, districts, and schools have a built-in incentive to hide the truth from parents and the public. Every big school district should have an organization like the UChicago Consortium on School Research keeping it honest.

Second, there are no good schools without good principals. Every attempt at improvement stands or falls on the quality of the person leading the school and driving the change. Good principals attract, develop, and retain good teachers. While policy matters at the state and district levels and good teaching happens in the classroom, the school really is the unit of change — and principals are the ones driving it.

And finally, the politics of mayoral control cannot be discounted. Most Chicago taxpayers do not use the public schools, yet Daley and Emanuel raised local taxes to the maximum year after year to balance budgets and boost teacher pay. They tirelessly rallied businesses and foundations to invest in public education.

Both mayors spent their limited political capital in Springfield year after year to pressure the state for more funding. They borrowed incessantly to the detriment of their bond ratings to protect classrooms and stabilize teacher pensions.

In exchange, Chicago’s mayors brought choice, accountability, quality, and rigor into the system, and they took a lot of heat for it. Absent their leadership, Chicago would not be where it is today.

Disclosure: Peter Cunningham was an assistant secretary for education in the Obama administration; an aide to Mayor Richard Daley when he assumed control of Chicago Public Schools in 1995; a consultant to Chicago Board of Education President Gery Chico in the late 1990s; and a senior adviser to then–CPS Chief Executive Officer Arne Duncan from 2002–08.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)