74 Interview: Class, Race & the Pursuit of College. Veteran Journalist Paul Tough Addresses Higher Ed Admissions, Mobility Myths and What His Critics at the College Board Get Wrong

See previous 74 interviews: Chicago Public Schools CEO Janice Jackson on getting students to — and through — college; civil rights activist Dr. Howard Fuller talks equity in education; and United Negro College Fund CEO Michael Lomax on guiding low-income students to college graduation. See the full archive here.

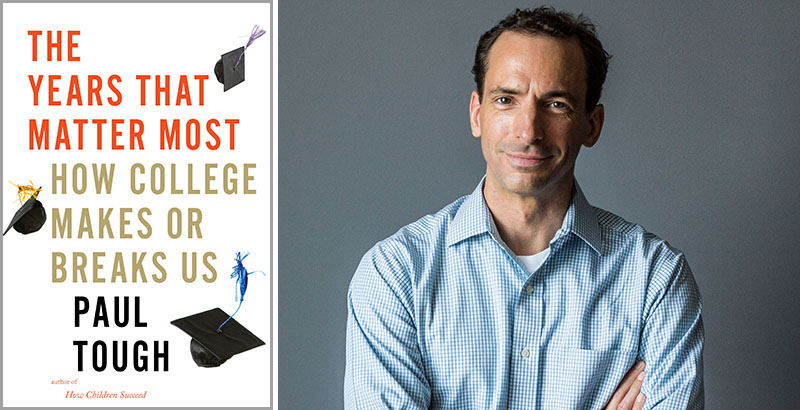

Journalist Paul Tough has spent a decade helping readers understand how children learn. His three previous books have detailed the complexities inherent in helping young people succeed in school — and the ways in which education systems often fall short, especially for low-income kids. A master explainer, Tough has also helped popularize the works of educators and researchers such as Geoffrey Canada, Angela Duckworth, James Heckman and Kirabo Jackson.

In his new book, The Years That Matter Most: How College Makes or Breaks Us, Tough, himself a college dropout, turns his attention to the pivotal role that higher education plays in young people’s lives — and the struggles that many of them endure to get into college and stay there.

Tough interviews not only educators and researchers but also college admissions directors and, of course, students making their way through the transition from high school to college.

In the end, he finds lots to worry about. Our higher education system, he writes, is “a mobility engine that functions incredibly well for a small number of people and quite poorly for others.” The wealthy, the talented and the well-connected do just fine. By contrast, those from families that are “deprived or isolated or fractured or all three” tend to benefit least.

Tough notes that in the first few decades of the 20th century, when more sophisticated workplace technology demanded a higher level of education, communities responded by essentially creating the free public high school system. After World War II, when millions of high-school-educated returning veterans sought to enhance their skills, the U.S. complied: By 1948, fully 15 percent of the federal budget was claimed by the G.I. Bill. But 70 years later, Tough concludes, Americans still believe in the “transformative power” of a college education, but the message to most young people is “You’re on your own. You figure out how to get the skills you’re going to need. And by the way, here’s the bill.”

He also takes on what he calls the College Board’s enormous power and influence over the higher education landscape, saying the nonprofit must come to terms with the SAT’s role in inequity — but he concludes that, based on its reaction to his book, it likely won’t anytime soon.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The 74: You begin The Years That Matter Most with a remarkable scene, with you sitting beside a low-income, high-achieving New York City high school senior as she checks her phone to learn whether she has gotten into Penn, her dream school. I won’t give away what happens, but why did you begin this way?

Paul Tough: Shannen Torres is a remarkable person, and she was a remarkable subject to encounter as a journalist. I think what makes her story so effective in introducing the book is that she, more than any other student I got to know in my reporting, was a true believer in the idea of American social mobility and the power of higher education to help her achieve her dreams. Applying to college tested her faith, and that moment waiting for the results was the greatest test of all.

Her story also helped illuminate some central questions about the value of college, questions that run through the entire book: Is college worth it? Can a college education really change your life? And is the system truly fair and meritocratic?

The 74: Early in the book, you introduce the work of Raj Chetty, the Harvard economist who has changed the way many of us think about the value of college. How would you describe Chetty’s breakthrough? Why is it so important?

Raj and his colleagues were able to analyze decades of tax data to show the effect that each individual’s path through college has on his or her economic standing as an adult. That allowed them to demonstrate two important but somewhat contradictory trends.

First: For certain individuals, a college education really does create mobility, placing students who grew up in poverty on a more or less level economic playing field after graduation with their classmates who grew up in affluence.

Second: Most low-income students don’t get a chance to experience that mobility. The student bodies at our most highly selective institutions are so dominated by students who grew up in affluence that those schools have little room left for the low-income students who would benefit most from the education they provide.

The 74: In a way, that combination seems like the worst possible scenario. What part do gatekeeper tests like the SAT and ACT play in this process? How are the tests — or the way they’re weighed — changing?

I don’t think the tests themselves have changed much. Standardized tests have always given an admissions boost to families with higher incomes, and they continue to do so. During the years I was reporting the book, the College Board revised the SAT and announced a number of initiatives designed to counteract the widespread perception that the test promoted inequity in higher education admissions. Those initiatives were introduced with great fanfare, but in the end, not much changed in those years — except the College Board gained back a lot of the market share that it had lost to the ACT.

The College Board’s data continue to show that the students who benefit most from an admissions system that emphasizes SAT scores are disproportionately wealthy and white or Asian and tend to have well-educated parents. Meanwhile, low-income black and Hispanic students with less-educated parents continue to benefit more, on average, from an admissions system that puts less emphasis on test scores and more on high school grades.

The 74: On a related note, how is test-optional admissions changing the process? As you say, “If the University of Chicago doesn’t need the SAT, who does?”

The test-optional movement seems to be slowly expanding. I reported on a few different institutions that are using test-optional admissions, and some of them are now able to analyze the policy’s impact on their enrollment patterns. The most promising data I saw came from DePaul University, which found that after the school went test-optional several years ago, students who were admitted without submitting their test scores succeeded at and graduated from DePaul at about the same rates as score-submitting students. That was despite the fact that non-submitters were disproportionately lower-income, first-generation students of color and did in fact have lower test scores, on average, than their classmates. (The non-submitters agreed to share their scores with DePaul, for research purposes, after they were accepted.)

The conclusion DePaul’s admissions office drew from those data was that the non-submitters’ lower test scores had essentially been a false signal, warning of an academic disaster that never arrived. When the admissions officers were able to avoid the distraction of those signals, DePaul was able to enroll promising low-income students its admissions office otherwise would have likely missed.

That said, it’s important to note that a test-optional admissions strategy alone isn’t a magic bullet that will solve the inequities that pervade college admissions. The intense financial pressure many private institutions feel these days often compels them to admit students based on their ability to pay tuition. Test-optional admissions offers no protection from that pressure.

The 74: You write about Harvard economist Caroline Hoxby’s work on “undermatching,” in which qualified low-income students simply don’t apply to elite colleges that match their skills. What have become of her (and others’) efforts to fight this?

To be honest, the state of the undermatching research is pretty confusing right now. The original 2013 study by Hoxby and Sarah Turner seemed to show promising signs that a simple, inexpensive intervention — information packets mailed to high-achieving low-income high school students — could have a significant impact on students’ undermatching behavior. But a large-scale, multiyear replication of the experiment by the College Board didn’t produce significant effects. Hoxby has told reporters that the College Board did a poor job replicating the original study. The College Board says it doesn’t know exactly why the replication didn’t work. So it’s not at all clear now how the field should move forward.

As I report in the book, the College Board’s leaders had clear indications back in 2016 that their replication study wasn’t producing positive results. Internally, they debated whether they should inform the public of their findings in an academic paper. But they decided against it, telling me at the time that they had “concerns about how a formal research paper might be received externally.”

I think that was an unfortunate decision. If in 2016 the College Board’s researchers had instead chosen the path of transparency and openness, other researchers and administrators and philanthropists might then have spent the last three years analyzing and debating the results and using those findings to adjust and improve their own interventions. That’s how science is supposed to work. Instead, the College Board shared nothing, closing down its replication in 2018 and neglecting, even then, to tell the public why.

Only recently did the College Board’s leaders finally get around to releasing some data about the replication. Perhaps coincidentally, they chose to do so just after my book had gone into production.

[Editor’s Note: In a statement to The 74, the College Board said it published the results of its research in May, well before it received a copy of the book; a College Board spokesman said researchers presented their findings at a November 2018 conference. Tough notes that he was referring above to the College Board releasing its data just after his book went into production, not before it received the book. In a separate statement released when Tough’s book was published, the College Board said it made “a significant investment” to replicate Hoxby and Turner’s experiment on a much wider scale and saw “small but initially positive results.” It ultimately published research that found the results “disappointing.” The organization admits that it fell short in not sharing this information “in a timely way along the way, despite stating we would. Our uncertainty about the evidence made us reluctant to enter a public dispute until we were more sure of the facts. We should’ve shared preliminary results along the way rather than waiting for the definitive findings.”]The 74: Since the book appeared, the College Board has taken the unusual step of releasing a lengthy statement in response, alleging that your reporting “grossly misrepresents” its work to serve more students. The statement is seven pages long and alleges that you “most egregiously distorted,” among other things, their work on the Hoxby research and the effectiveness of their free SAT practice on the Khan Academy website. What’s your response to their basic complaint?

The College Board is a huge, well-funded organization that brings in more than a billion dollars a year in revenue, and when that revenue is threatened, its leadership tends to get defensive and lash out. This statement is a prime example. It is not a persuasive critique: It fails to address the most serious findings in my reporting and instead nitpicks over trivial points. It fudges details and misleads readers about dates. It contradicts itself and undercuts previous claims by the College Board’s leaders. But its purpose isn’t really to rebut the facts I reported; it is intended only to surround those facts with a fog of doubt. It is the equivalent of shouting “fake news” — though the College Board uses the more erudite “false narrative.”

There are a lot of smart, well-intentioned people who work for the College Board, and I think many of them were hoping that the organization might use my book’s publication as an opportunity for genuine change and reform. But, clearly, there were others within the College Board’s leadership who favored a scorched-earth strategy in response to the book’s revelations: Admit nothing, deny everything, attack the messenger.

It is a disappointing choice. The College Board wields an enormous amount of power and influence in higher education. If it chose to, it could use that power to make changes that would truly benefit students like the ones whose stories I told in my book. But first, it would have to deal honestly with the role of the SAT in higher education’s inequities. This latest PR campaign makes it hard to be optimistic that the College Board is going to choose that path anytime soon.

The 74: In addition to examining the latest research and talking to folks on all sides of the issue, you also spent a lot of time on actual campuses, in the admissions offices of elite colleges and universities. What surprised you most?

I was surprised by how hard that job is! Admissions directors — or enrollment managers, as they’re more commonly called today — sit at the nexus of a lot of powerful and conflicting forces on college campuses. Publicly, enrollment managers are in charge of admitting a brilliant and diverse freshman class each year, which is a hard enough task on its own. But behind the scenes, they have a second job that is at least as important: They are responsible for bringing in enough revenue from tuition to keep the institution afloat. The conflict between the public mission and the private one is rarely expressed publicly — but it is at the heart of what makes admissions work so challenging today.

The 74: You have a very interesting personal history with higher education, stretching back more than 30 years. How did it shape your attitude about the value of a bachelor’s degree?

Yes, I dropped out of college twice — first from Columbia, then from McGill — and I never went back to complete my B.A. I can definitely see the irony in the fact that as a college dropout I just spent six years reporting on college campuses. But I decided not to write about my own college experience in the book, in part because I don’t think it’s fair or useful to extrapolate from outliers like me. I did manage to have a career in journalism without a B.A., but that was a rare occurrence even in my day, and it has become much more rare today.

But I do think my personal skepticism about college during my student days has helped give me some insight into the anti-college mood on the rise now in many parts of the country. I understand why some people don’t want to believe that a B.A. is useful or necessary. When you look at the data, it’s hard to deny how valuable a B.A. is for a young person’s prospects. But still, I’m sympathetic to the wish that young people had reliable alternative pathways to economic security and mobility.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)