74 Interview: Longtime Civil Rights Activist Howard Fuller on Trump, DeVos, and What It’s Like to Advocate for School Choice in an Age of ‘Hypocrisy’

See previous 74 interviews, including former U.S. Department of Education assistant secretary for civil rights Catherine Lhamon, Indiana educator Earl Phalen and former U.S. Department of Education secretary John King. The full archive is right here.

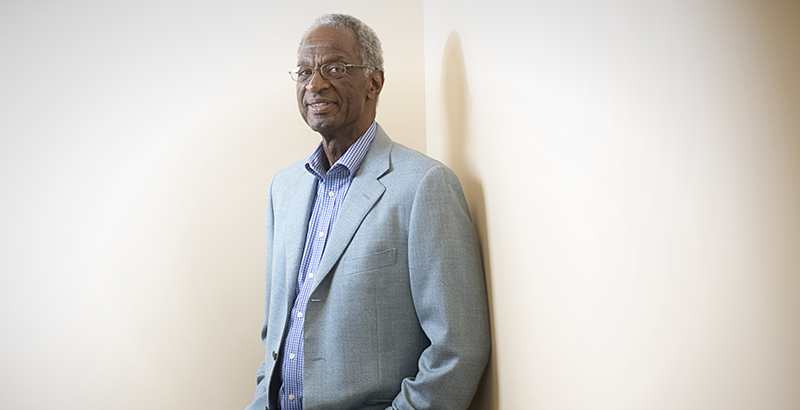

It’s a complicated moment both for longtime school reform advocate Howard Fuller and the choice movement he’s spent decades fighting to advance.

Like Fuller, U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos and President Donald Trump have championed school choice measures like vouchers and charter schools. But a shared belief in choice is tempered by Fuller’s open contempt for the president, a man he once called a “despicable human” and sees as divisive and racist.

As we went to press, the Department of Education announced it had rescinded Obama-era guidelines on affirmative action that encourage universities to use race as a factor during admissions. Even though the guidelines weren’t legally binding, the move represents the latest example of the Trump administration’s efforts to scale back measures that reach for racial equity.

However, neither Trump nor DeVos can be the face of school choice, Fuller argues. No politician can. The issues, and the needs, are bigger than any one person, he said. Still, the opposition to Trump and DeVos is a force that charter schools and reform advocates are being forced to reckon with.

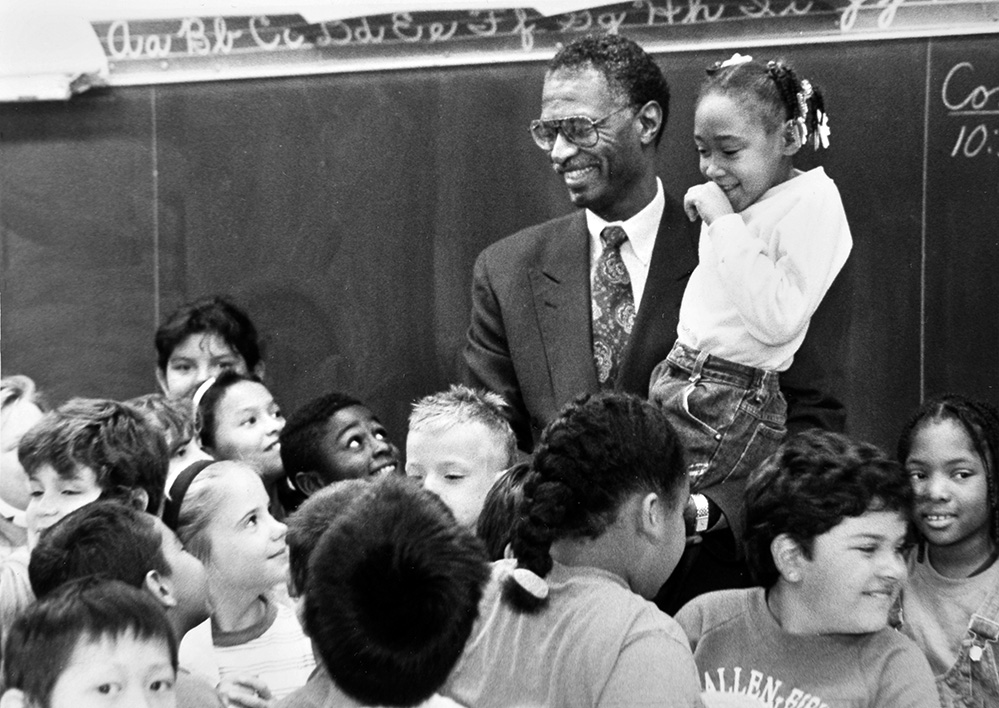

Fuller believes deeply in the intrinsic value of a parent’s right to choose — a position that predates his term in the early ’90s as the Milwaukee school district’s superintendent and was central to his efforts to push for the state’s parent choice program. As home to the nation’s longest-running voucher program, now approaching its 30th anniversary, Milwaukee offers perhaps the longest view on their effectiveness.

The results are mixed. In general, test scores at Milwaukee voucher schools are no better than at traditional public schools — both well below state averages — though one study found that students using private school vouchers were more likely to graduate from high school and enroll in four-year colleges.

And that’s still separate from the argument that both vouchers and charter schools siphon students and money from the traditional school system, spreading resources too thin.

Fuller isn’t deaf to the fiscal argument, nor has he closed his mind to the possibility that voucher schools could benefit from a stronger accountability system. In a recent interview with The 74 at his Marquette University office in Milwaukee, Fuller tackled those topics and more. The conversation was edited for length and clarity.

The 74: You’re at an interesting intersection as someone who has advocated for school choice for decades. Now we have a White House administration that champions the same approach, but a president whose comments have been perceived as very hostile to communities of color. How do you navigate that?

Fuller: First of all, I have known Betsy DeVos for maybe 16 or 17 years. I’ve not had a conversation with Betsy in five years. When she was up for secretary, they asked me to do a video in support of her, which I did based on our personal relationship, based on the fact that she supported work that I had been doing, particularly around trying to get more black Democrats to support parent choice.

So I know Betsy and respect her as a person. I’m not going to be one of those people who’s going to engage in demagoguery about her.

The problem, however, is that Betsy works for a person who I think has done tremendous harm to the community and the people I represent. I think this man is clearly racist. I think that this man has said and done things that have divided this country even more than it was already divided. And so for a person like me, even though I respect Betsy personally, it’s not possible to work with the administration, even on issues that I agree with, because for me, it’s a matter of principle. It would be as if I am condoning the kinds of things that Donald Trump has done.

I’ve been one who has always been able to work both with Democrats and Republicans. I took a lot of criticism for working with George W. Bush. But for me personally, George Bush was a decent human being. Whereas with Trump, it’s totally different. For me, that line is not a line I can cross. I have good friends who work in the administration, who work for Donald Trump, and I don’t respect them or care about them any less, but being able to work with them is not possible. It’s just impossible.

I’ve talked to dozens of charter school leaders in Southern California, and none of them have really expressed any excitement for Betsy DeVos. I get the sense, in fact, that some feel DeVos and the administration could do more harm than good for charter schools and the school choice movement. Do you worry about that?

Around the time of the election, a woman named Robin Harris and I did an article for The Hechinger Report. The point that we were trying to make was that neither Betsy nor Donald Trump could ever be the face of parent choice. But that wasn’t just about Betsy or Donald Trump; it was about any politician. To me, the face of parent choice are the families that benefit from being able to make these choices.

I had the same criticisms thrown at me for working with the Bush administration. But those criticisms meant nothing to me because I just felt like we were aligned on parent choice. We were not aligned on a whole bunch of other issues, but George Bush was not saying and doing the same things that Donald Trump is doing and saying.

“I think this man is clearly racist.”

From my standpoint, I’m going to engage in fighting for parent choice at a local level. I’m going to work in the communities that I’m working in as hard as I can to make sure that low-income and working-class parents have a choice, to make sure that kids have an opportunity to get a decent education; I’m going to push back against any kind of policy initiatives that would somehow try to end that ability of people to choose.

But in the current environment, it is more difficult. But just because it’s difficult, it’s not going to stop me from standing up and supporting the things that I support, and whatever criticism comes with that, it comes. I’ve been criticized one way or another for 30 years.

Have your views on school choice changed or evolved in light of the current administration?

I’ve concluded that over all of these years, when it comes to education, I’m on a rescue mission. I don’t view my work in education as bringing about systemic change. I’m trying to rescue as many kids as I can to create an educational environment that will give them a chance to change their life trajectories.

I haven’t changed my views on choice at all. I’m more adamant than ever that low-income and working-class people need choice. Because I care about these kids, I cannot be unmindful of all the things that they’re dealing with before they ever get to school, so their health care is important to me. Whether or not they have housing is important to me. Whether or not their families have jobs is important to me. Whether or not those jobs pay a living wage is important to me.

I’ve had these debates and discussions with people over the last couple of years about whether or not education reform begins or ends at the schoolhouse door. But it doesn’t begin at the schoolhouse door and it doesn’t end there. If you care about these kids getting an education, you have to care about all of the other things happening to them.

For example, how can I say that I care deeply about these children and not be concerned that we’ve created an environment in this country where Latino families or other immigrant families are worried about being deported? How can I say I care about these kids and not care about the fact that now some are being bullied because they’re Mexican, because we’ve created this environment of hostility towards immigrants and people of color?

I understand you don’t want to talk about DeVos personally, but do you diverge from any of the policies or decisions she’s prioritized?

I’m obviously concerned about what is and is not happening on the civil rights front within the department. I’m concerned about transgender kids, and I’m concerned about what comes out of that department, and how it affects these kids. I’ve not spent a lot of time speaking on any of those issues, quite frankly, because a lot of what’s going on has almost no impact on what is going on with my kids. I try to spend my time really focused on the things that have the greatest impact on the kids I’m working for.

That said, as much as I support vouchers, I could not be in the position to say I would support a federal voucher if the way to get it would be to take money from Title I.

Because for me, it’s not about taking money from poor parents. It’s about trying to get them more resources, not less. I’m pleased that there’s additional money for charter schools, but I’m always concerned about where that money comes from.

There was a line in a recent Milwaukee Journal Sentinel column that suggested you’ve retreated a bit from education politics. In it, you said that after a while, people just stop listening to you. But you obviously haven’t totally retreated. After all, you’re here, talking to us …

No. I think I’m fortunate in that I don’t think people have quit listening to me totally yet. But the point I was trying to make is there does come a point — it’s just reality — where there’s a new generation of people, new ideas, new thoughts, and it’s just no longer your time.

I feel like I’m still adding value because I spend almost all of my time, obviously, talking to younger people because most people are younger than me. But I try to be open to new ideas and new ways of thinking. I don’t come at young people like, “Hey, I got all of this knowledge. You all should listen to me.” That’s not how I function. I function in a way where I try to give people the benefit of what I’ve learned, but I’m also trying to learn from them because I still believe learning is a two-way street. There’s some things I can impart to young people, but there’s a whole lot that I can learn from them.

To that extent, I hope that my ideas and my ways of operating are still relevant, but I was just trying to make the point that people just get tired of hearing you. Can somebody else talk instead? I feel blessed that I don’t think I’ve reached that point yet.

We’re here in Wisconsin and it’s not even news that disparities between white and black residents are some of the starkest in the nation. In fact, that’s the case on almost every measure, from low birth weight to the achievement gap and incarceration rates. What do you think sets these realities in place — and what do we do about them?

I wake up every day asking that question. I had sent out an email when the NAEP scores came out earlier this year, just as I sent out an email in 2010 when the NAEP scores came out. It has gotten worse for black fourth- and eighth-grade readers. We’ve fallen behind states like Florida that made certain policy changes that we did not make, and I think we’re paying the price for that.

The honest answer is, I don’t have an answer for why these things occur. I don’t think that the body politic writ large really cares about what is happening to poor black and brown people. Everybody talks about what we gotta do for the middle class, and I don’t have any issues with that, but what about poor people? What is it that we’re going to change? What is it that we’re going to do to make sure that people have decent housing? To make sure that people have health care? To make sure that people are not starving? These are real issues for the people that I care about, but I don’t think that the body politic writ large has that as a primary concern on their agenda.

“I’m a pessimist. But my pessimism doesn’t dampen my willingness to get up every day and fight … I think you fight because not to fight is to co-sign on the injustice.”

If you go back to World War II when Europe was destroyed, they came up with a Marshall Plan for how to reconstruct Europe. My view is that if America really cared about our poorest people, we would construct policies and put money behind a plan to change that. We spend billions on things that the people in charge care about. We come up with tax cuts.

For the people — the kids — who I care about in the city of Milwaukee, I don’t think their needs and their interests are at the top of the agenda of people who make policy in this country. So it’s important for people like me, to the degree that I can, to raise my voice for them, because if some of us don’t continue to raise our voices, there’s not going to be any change. But we’re up against very, very difficult circumstances because the kinds of issues you and I are talking about are not the issues at the top of the political agenda in this country.

I’m a pessimist. But my pessimism doesn’t dampen my willingness to get up every day and fight. I really believe something that Derrick Bell taught me in his book Faces at the Bottom of the Well. He was talking about the fact that racism is woven into the fabric of American society and that it’s permanent.

The question is, if racism is permanent, or if some of these conditions seem almost unsolvable, then why do you fight? Why would people fight when victory does not seem possible?

I think you fight because not to fight is to co-sign on the injustice. I get up every day to fight even if I don’t see a pathway to change because not to fight, not to raise my voice, is to say that this is OK. I’m not willing to do that.

And you believe school choice is one way we can start to right the balance?

I support “parent choice” as opposed to “school choice.” For me, it’s more than a semantical difference. I didn’t get into this to empower schools. I got in it to empower parents. I want parents to have the power to choose; I don’t want schools to have the power to choose them. Some people don’t make that distinction. For me, it’s an important distinction to make.

I don’t think that parent choice solves all problems, nor is parent choice without its downsides. I’ve never seen a public policy that only has an upside. I just don’t believe that there ought to be an America where only people with money have the ability to choose the best option for their children.

WATCH — In 2015, Dr. Fuller Talked With The 74 About the Future of School Choice:

What gets me is the hypocrisy around parent choice. You’ve got people with money who know that if schools don’t work for their kids, they’re going to move to communities where they do work. They’re going to put their kids in private schools or get the most expensive tutoring on the planet. They don’t care what government reports come out about testing or anything else. But yet, we want poor people to stay in schools that don’t work for their kids so everybody can keep getting paid. Parent choice is just one lever that I would want poor people to have as they continue to struggle to change the lives of their children.

And one thing I want to say is, I’ve never been in this fight to just talk about the future. People keep saying, “Oh, we need to save our children because it’s about the future.” No, it’s about the present. It’s about these kids’ lives today. It’s not about some future reality. It’s about how you change their reality today. Nothing that anybody has said to me over 30 years has changed my opinion on that at all. In fact, it’s made me even more firm on the importance of having this.

A recent report tried to quantify the financial impact that charter schools have on California school districts. The idea was that you’ve got different sectors — traditional schools, charter schools — but only a finite amount of money to support all of them. Do you believe that embracing alternatives like vouchers or charter schools makes it more difficult for the traditional school district to support its students?

Here’s the thing: America is really good at making people make false choices. For example, people have decided now that early childhood education is crucial, so are we now going to abandon kids in high school and middle school and put our resources into early childhood? Are we going to make an argument that the “richest country in the world” has to make those kinds of choices? Are we going to argue that we don’t have the resources to allow dollars to follow students?

What happens is, no one comes up with a study about what happens when people with money flee the city and go to the suburbs and create these white enclaves. I ain’t seen no study about the impact of that on the city of Milwaukee.

You want to start talking about what has an impact on city school systems? Then let’s talk about all of the departures. And the people doing these studies, I’m sure that they’ve done studies on the impact of the change in housing patterns. What are the policy decisions made every single day that put poor people in a place where they have relatively few resources?

“I believe that parent choice is widespread in America — unless you are poor.”

So all of a sudden, we’re going to pick out the fact that some poor people get the ability to choose a better education for their kids, and we’re going to write studies about the financial impact that it has on the district? That, to me, is just another sign of the hypocrisy in this country. We choose where we want to focus. We never focus on what happened when funding formulas were changed. Go to a place like Connecticut and look at the way that they fund certain communities versus others. No, we’re going to focus on the relatively few people who have the ability to take tax dollars and put it in a different learning environment, and we’re going to put the blame on them.

I’m not buying into any of that, but I’m not going to sit here and argue that kids leaving has no impact. It does. The most immediate way to change that, of course, would be to have those kids get a great education. If they were getting a great education, they wouldn’t be leaving in the first place.

There’s just all kinds of different ways to argue this. No matter what kinds of studies come out, no matter what kind of graphs people put together, I have a stake in the ground that says that poor parents and working-class parents ought to have the ability to choose the best educational environments for their children. Period.

I believe that parent choice is widespread in America — unless you are poor.

One of the concerns about voucher schools is that they don’t have the same accountability and oversight as traditional public schools. Don’t you think all schools should have the same oversight?

I actually have evolved on this issue. I’m for a strong accountability system, but accountability isn’t just test scores. I think there needs to be a variety of different ways to determine the value that schools bring. But I think it’s a valid argument to say that if we’re going to use public dollars, then the public has a right to know what is happening with those dollars. I personally support an accountability system that includes all schools.

But what you should know, though — and this is something that people never talk about — when the voucher bill was first passed in 1989 and later went into effect, the union said, “The way to kill this program is to call for more regulation.”

There was a rationale for that, because when the Supreme Court in Wisconsin ruled that the program was constitutional, one of the reasons was because there was not excessive government entanglement. So the union said, “The way to do this is to call for more regulation under the banner of accountability, and then once we get all of this stuff, let’s take them back to court on excessive government entanglement.”

So some of the arguments against accountability weren’t that we didn’t want there to be accountability; we were concerned that was a subterfuge to, in fact, create an environment that would then make the programs illegal. For me and people like me, the resistance to “accountability” was that.

The second thing was, you had all of this accountability and kids were failing, so what good was this great accountability system doing? It wasn’t like because of this accountability system, we were creating great schools for kids. Then the issue became: Where is the sweet spot between accountability and autonomy that gives you the ability to make changes you need to make for kids?

Like a lot of these arguments, they never take place in a politically neutral environment. There are people in the parent choice movement who disagree with me on this issue of whether or not we should all be in the same accountability system. If other things are held constant, like equity and funding, I would support a common accountability system.

We’re coming up on the 30th anniversary of the parent choice program in Wisconsin. So in some ways, Milwaukee has the longest view to see how effective it is. And yet, as we talked about earlier, it still has some of the most dramatic and concerning achievement gaps between students. Do you think that’s an indication that the program isn’t working?

I’ve come to the conclusion that choice has a value in of itself, that the power of people to choose has a value that should be judged independently of whether or not they’re in a great school. For example, a voucher is not a school; it’s a financial mechanism. We have to work to create great schools, but our inability to create great schools should not therefore be an argument to end vouchers.

Because if we use that argument, then we should get rid of the public school system as well because clearly, the public school system has made great schools, but not all great schools. Nobody makes the argument that “OK, since Milwaukee Public Schools has not created all great schools, let’s get rid of the Milwaukee public school system.”

If you ask me, “Has the program been successful?” I would say, “Yes,” because it has given people an option who never had one before. It’s clear that there are thousands and thousands of kids who have benefited from the existence of the program. The problem that I have and the problem that anybody would have who really cares about kids is that we still have a lot of work to do to make sure that the schools that kids are going to are delivering quality instruction.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)