14 Charts That Changed the Way We Looked at America’s Schools in 2019

By Kevin Mahnken | December 11, 2019

This is the latest in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing education into focus through new research and data. See our full series.

Updated December 12

When it comes to research, a picture tells a thousand words.

Whether you’re measuring student test results, demographic figures or one of the thousand other items of statistical effluvia that float through the education landscape, it helps to have a visual aid. Take it from an education reporter: Untethered to a simple bar graph, critical findings on the success or failure of a major school reform can be reduced to so many figures in an appendix.

That’s why this year, as in 2017 and 2018, we’re presenting the most striking images from education research over the past 12 months. They help illustrate important studies into school funding disparities, college dropout rates and shifting public opinion. And with a minimum of verbiage, they let the reader know what matters in education research.

Here are 14 discoveries that changed the way we think about education in 2019:

Integration: Exam Schools May Hurt Disadvantaged Students More Than They Help

Seats at urban “exam schools” — public institutions like Boston Latin and the Bronx High School of Science, which accept exclusively high-performing students on the basis of competitive admissions criteria — are some of the hottest tickets in K-12 education. They’ve also become an object of contention in recent years, as many have noted the schools’ lack of racial diversity. Many observers, pointing to the tiny number of black students accepted to New York’s prestigious Stuyvesant High School this spring, have called for city and state authorities to eliminate entrance examinations and press for more low-income and minority students to receive admission.

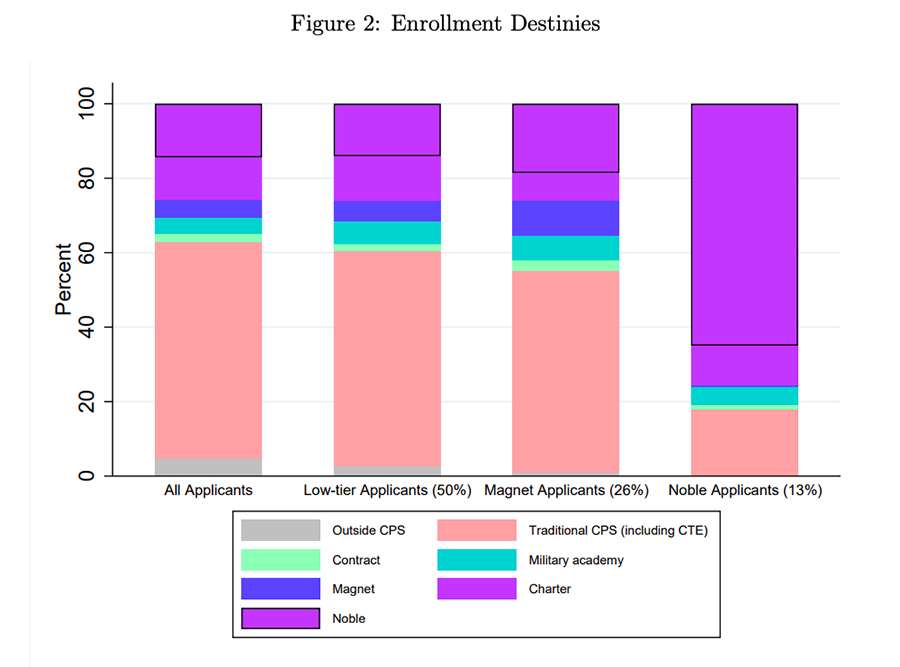

But new research on selective high schools in Chicago may give activists pause. Gathering academic and college admissions data, two studies suggest that disadvantaged students admitted to the city’s 11 exam schools actually end up worse off than demographically similar peers.

Neither paper found that the students, offered seats through a form of socioeconomic affirmative action, struggled to keep up with academic work at the high schools; but they realized no learning gains in math or English, and they were somewhat less likely to enroll in competitive colleges than similar pupils who weren’t accepted, perhaps because their GPA and class ranks were lower than they would have been otherwise.

“So much media attention and political energy goes into discussions of who gets to go to exam schools,” said co-author Joshua Angrist, an economics professor at MIT. “We’re basically saying, ‘You’re arguing over something that may not be worth much. Your view of this is potentially being distorted by a misreading of the facts.’” (Read more from our September coverage of the study.)

Equity: School District Borders Segregate Millions of Kids Based on Race and Revenue

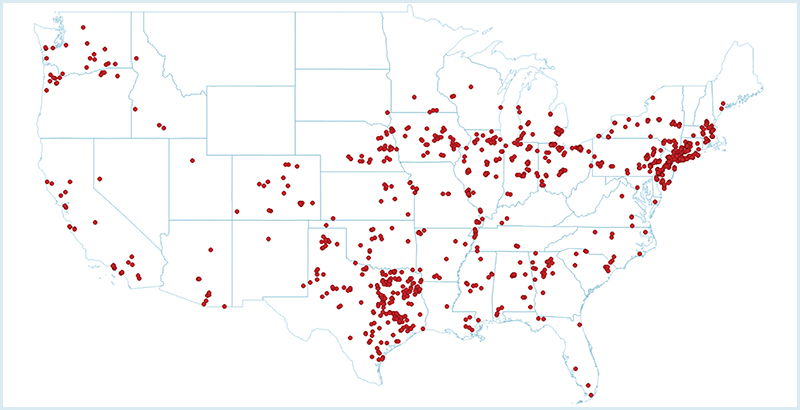

The lines between school districts are some of the most intractable impediments to nationwide education reform, but also some of the most underappreciated. While advocates debate furiously over issues like curriculum, standardized testing and school accountability, those lines divide and define educational communities: white and nonwhite, affluent and poor, professional and working-class. With so much of school funding dependent on local tax bases, the central question in school quality is often which side of a district border your family lives on.

Any homeowner who has scraped and saved to live in an area with desirable schools is somewhat aware of this phenomenon. But a report released this summer by the nonprofit EdBuild made it impossible to ignore. Studying thousands of school districts throughout the United States, the group found evidence of striking inequalities in funding between bordering school districts. No fewer than 9 million students live in districts that spend $4,200 less per pupil than neighboring districts. And in nearly 1,000 cases, the funding gaps between neighboring districts is greater than 10 percent.

The interactive publication was just one of a host of stark warnings issued by the group about the deep disparities in resources that pervade public education. It was also one of the last: This year, EdBuild also announced that it plans to close its doors in 2020. (Read more of our coverage from July on this study of school district borders.)

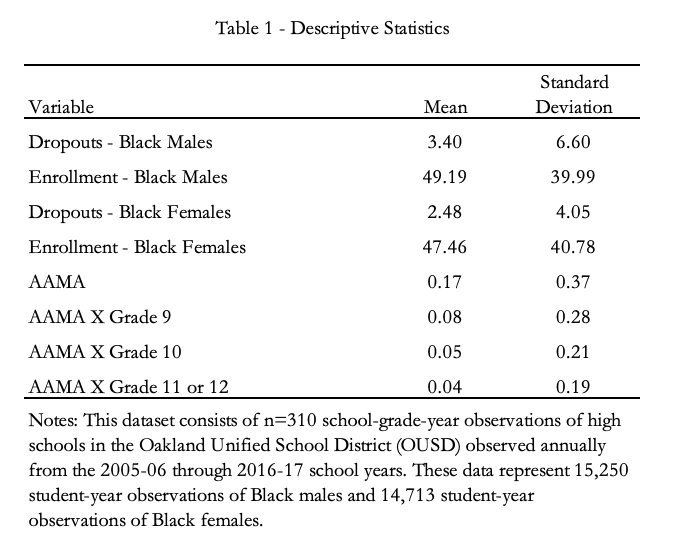

Curriculum: Oakland Sees Decline in Black Male Dropouts

Black male students are among the most underserved in the public school system, whether measured in test scores, disciplinary results or college enrollment. As a population, they have largely been failed by school reform efforts in recent decades. But a study based in Oakland offers some exciting evidence of a method that could improve at least one critical academic outcome. A program meant to break down stereotypes and build solidarity among black boys succeeded in cutting dropout rates for that group by 43 percent, the authors found.

Operated with the support of President Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative, the program enrolls black male students in special classes taught by teachers who look like them, and emphasizes black history and culture. Students also receive personal advice on higher education and career choices.

While questions linger as to whether the curriculum can be replicated outside Oakland, the district has already launched a similar, leadership-focused program for black girls.

Safety: Failing Schools Incubate Crime

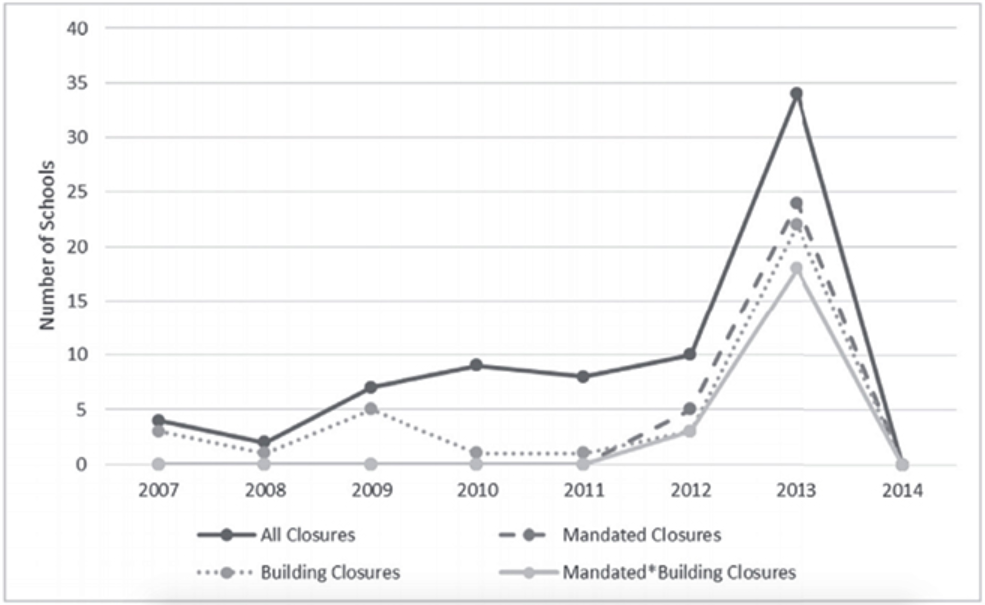

Shutting down underperforming schools is a heart-wrenching process. Families rely on them as local institutions, even if they don’t deliver top academic results, and when they go away, a piece of the community goes with them. That’s part of the reason the waves of school closures that have taken place in cities like New York and Chicago have led to bitter protests.

But a study by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania has found that closing poor-performing schools produces an unexpected benefit: greater public safety. By examining the targeted wind-down of 29 Philadelphia schools between 2011 and 2013 — a major shakeup of roughly 10 percent of the city’s school buildings — the authors found that crime rates dropped significantly following the closures. Violent crime, ranging from robberies to murder, fell by 30 percent, the analysis found.

The improvements were measured in census blocks around the closed schools during times when students normally would have been present, and the areas with the greatest numbers of displaced students saw the largest declines in criminality. Best of all, however, researchers found no evidence that, following the school closures, misconduct simply migrated elsewhere; no resultant spike in violent or property crime was measured in nearby areas. (Read more of our coverage of this study of Philadelphia school closures.)

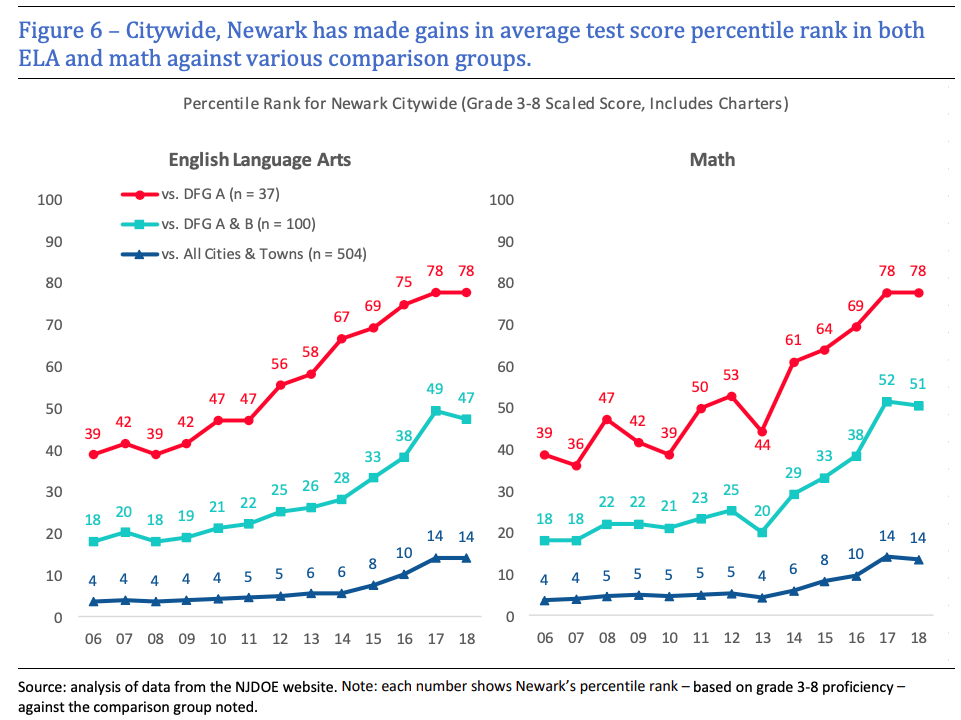

Cory Booker’s Legacy: Did the Newark Reforms … Work?

With the possible exception of New Orleans, Newark may be the American city most associated with the hallmarks of education reform.

The district underwent a state takeover more than 20 years ago, but its most ambitious period of change began under the supervision of then-Mayor Cory Booker, who took office in 2007. After his election, the city proceeded to shutter schools, replace principals, open new charters and take in millions of dollars in philanthropic funding from Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, all in the name of improving student achievement in one of the lowest-performing school districts in the country.

And according to a report released by researcher Jesse Margolis, the policy shift had big, beneficial effects. The study, funded by the nonprofit New Jersey Children’s Foundation, found that between 2006 and 2018, student test scores made substantial progress in both math and reading. Among low-income districts across the state, Newark’s performance improved from the 18th percentile to the 47th percentile over that period.

That means there’s still plenty of work left to be done. Now-Senator Booker has, until recently, been slow to defend charter schools as disenchantment around them has spread throughout the Democratic Party. But so far, at least, there’s good news for Newark families. (Read more of our June coverage on this study of Newark’s school reforms.)

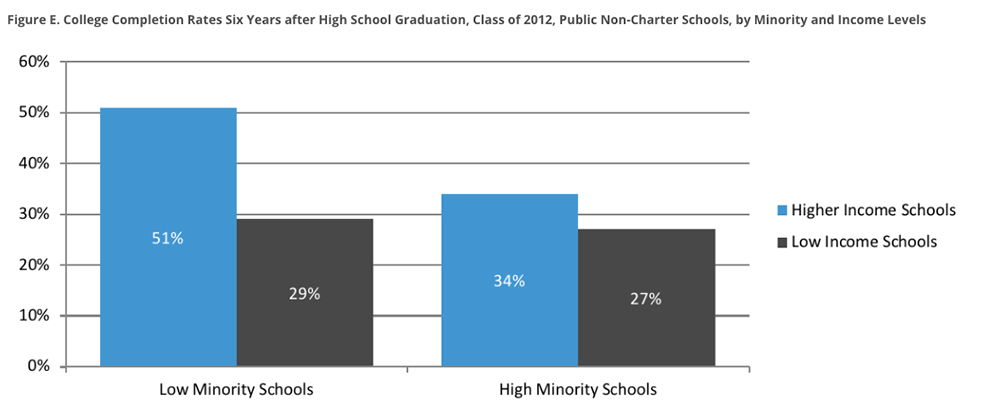

Higher Education: The Numbers Behind the Dropouts

Recent years have seen higher and higher percentages of high school graduates enrolling in colleges and trade schools, a happy development that will put millions more young people on the road to success in adulthood.

But that’s of no consolation to the 4 million college dropouts across the country, who cumulatively hold billions of dollars in debt from their aborted forays into higher education. An October data release from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center illustrated some of the grim realities behind America’s college completion crisis.

Among its findings: While majorities of graduates from all types of American high schools are enrolling in college, they are much less likely to graduate — even six years later. Just 1 out of 5 graduates from low-income schools, and less than 1 in 3 graduates from schools enrolling large populations of minority students, finish college within that period, the report found. (Read more of our coverage of this study of America’s college completion crisis.)

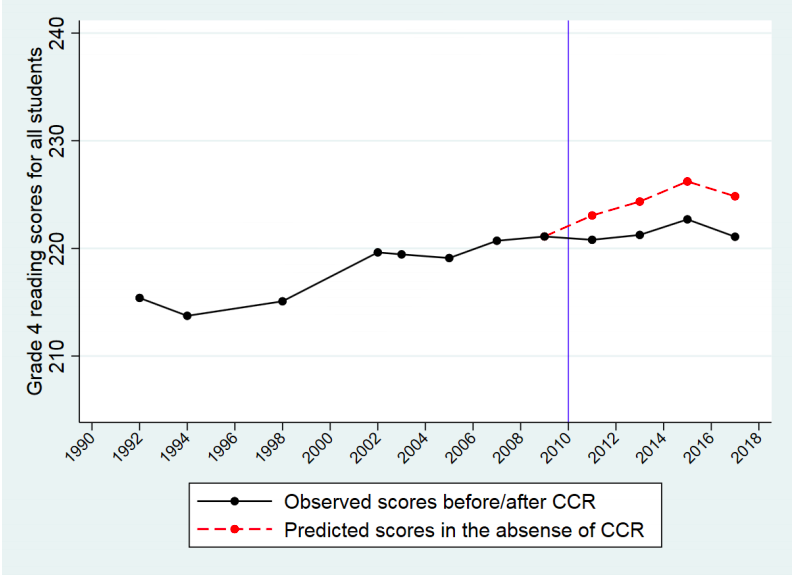

Standards: Common Core May Have Led to Learning Losses

If you weren’t living under a rock during the Obama presidency, you were at least dimly aware of the dispute around the Common Core State Standards. Initially a nonpartisan push for states to adopt rigorous academic expectations for students, the initiative devolved into a political crusade when the Obama administration incentivized the development of college-ready standards through its Race to the Top program. Seemingly overnight, conspiracy theorists linked Common Core to sex ed and Islamic indoctrination.

After the dust settled, however, most states had established some version of the standards, whatever they decided to call them. Now researchers are beginning to measure the academic impact of Common Core, and their findings aren’t encouraging: According to a study released this spring, states that adopted Common Core didn’t see better student achievement than those that declined; in fact, authors found, students in Common Core states saw slight declines in both math and English scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

While modest, the ill effects seemed to grow over multiple rounds of NAEP, offering a distinctly cautionary note around the reform. Although the research is some of the earliest to examine the effects of a sweeping change in educational practice, more is on the way.

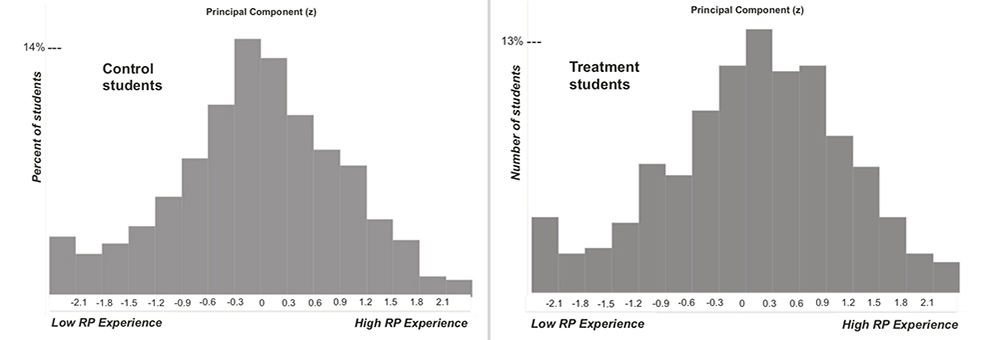

Discipline: Early Returns on Restorative Justice Are Mixed

Concern has grown in recent years over the effects of harsh school discipline practices, which fall disproportionately on black, Hispanic and male students. When schools suspend or expel their charges, some argue, they are separated from classrooms and put on a path to poverty and jail — a “school-to-prison pipeline” that denies educational opportunities to millions of pupils.

One trendy solution to school discipline problems has been restorative justice, a set of disciplinary practices that encourage dialogue and community healing over more punitive actions. The approach has spread quickly, but little in the way of robust research has pointed to concrete benefits or harms — until this year, when the RAND Corporation released two studies of the effects of restorative justice in classrooms. Neither provided blockbuster findings.

In one study, which randomly assigned schools in Pittsburgh to implement restorative justice, suspensions decreased, but not significantly more than in other schools at the same time (other studies have shown nationwide declines in suspensions in the past few years, as more attention has been directed at the issue). In another experiment, restorative justice schools in Maine saw no improvement in measures of school climate, such as bullying, in the wake of the changes.

The findings suggest that implementation of the new techniques remains a challenge: Restorative justice is voluntary, and children experiencing conflict with their classmates can’t be compelled to take part. What’s more, teachers need significant training to properly enact the necessary sequence of conversation and reconciliation.

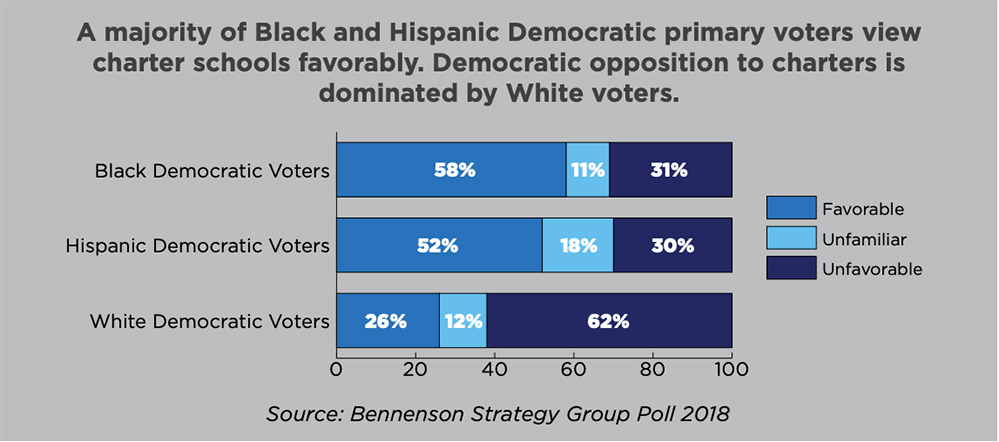

Politics: Democratic Support for Charter Schools Is Split on Racial Lines

Charter schools came about a generation ago, the brainchild of a technocratic movement to offer families more educational options and test-drive innovative educational practices. Since then, the American charter movement has relied on an ideologically diverse coalition of supporters — including both free-market conservatives and urban liberals — to foster its rapid growth.

After years of strain, that alliance has begun to split. As school choice is increasingly associated with the conservative policies of President Donald Trump and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, some Democrats have accused charters of a multitude of sins, from draining funds from school districts to funneling them toward corporate interests. Teachers unions, long critical of the nation’s creeping charter expansion, have also pushed their advantage. No surprise, then, that several leading candidates for the party’s 2020 presidential nomination have proposed new restrictions on charters.

As a 2019 poll from the pro-reform group Democrats for Education Reform shows, the ideological evolution reflects a racial split within the Democratic Party. While black and Hispanic Democrats look fairly favorably on public schools of choice, a whopping 62 percent of white party members view them critically. Opposition among whites has grown in recent years. (Read more of our coverage of this poll about Democratic views on charter schools.)

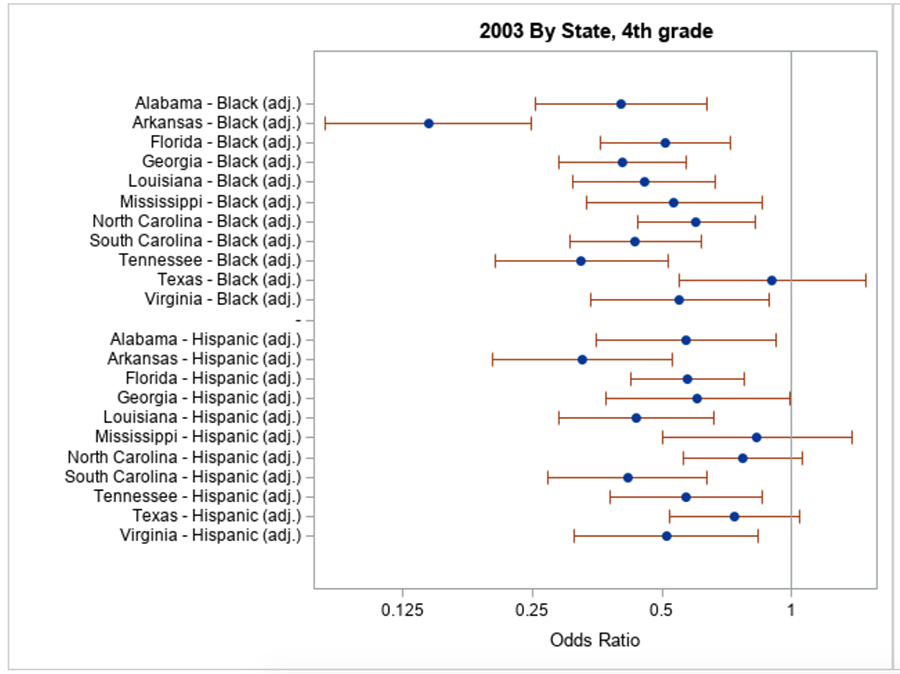

Learning Needs: Black Students May Be Under-Identified for Special Education Services

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 7 million American students received special education services in the 2017-18 school year, or roughly 14 percent of the nation’s K-12 population. Those students deal with a range of physical, behavioral, speech and developmental disabilities — from blindness to asthma to Down syndrome — that present challenges to learning, and federal law requires that they receive accommodations in the classroom.

For decades, education observers have worried that students of color are over-identified for special education designations. Teachers and administrators, the theory has held, are too eager to refer black students particularly to special education, resulting in many such students being needlessly removed from mainstream classrooms. To address those concerns, the federal IDEA law has been amended to require states to fix disproportionate identification of minority students.

But new research indicates that those fears may be misplaced. According to a study authored by academics at Pennsylvania State University and the University of California, Irvine, black students may actually be under-identified for necessary special education services.

In an analysis of 11 southern states, the researchers found that black students were 45 percent less likely than white students to be identified as having special learning needs — even when controlling for family income and academic achievement. Even among academically similar students at the very same school, the authors found, a white student is more likely to receive a diagnosis of disability than a black classmate.

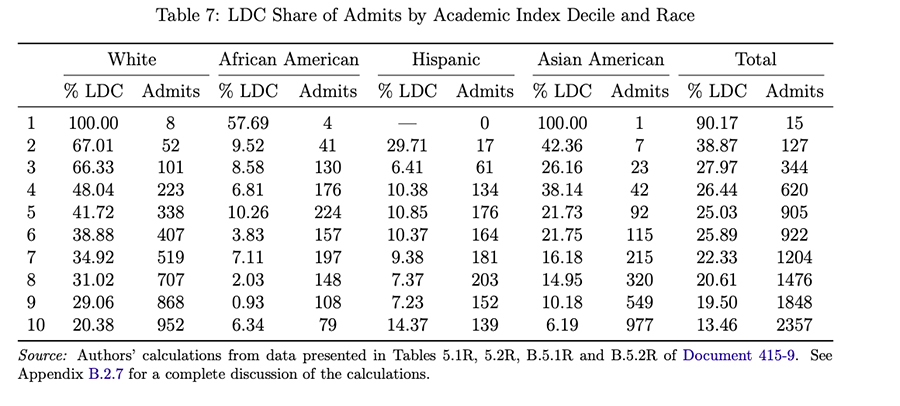

College Admissions: White Applicants Get a Leg Up From Athletic, Legacy Preferences

Elite colleges have been under fire for two years as scandals have erupted around their admissions practices.

First the Varsity Blues investigation showed the absurd, and often criminal, lengths wealthy parents went to in order to ensure acceptance for their children at fêted schools like UCLA and USC. Then a highly publicized lawsuit alleged that Harvard discriminated against Asian applicants; the case appears to be headed for the Supreme Court, and whatever its outcome, it has already uncovered unflattering documents showing how the school’s admissions office favors the children of affluent donors.

But a study circulated late in the year held even more damning revelations. Some 43 percent of white students accepted at Harvard were recruited athletes, legacies or the children of donors or faculty, the research found, and roughly three-quarters of them would have been rejected if they had been held to the same standards as white students who didn’t hold special status. If preferences for wealthy and athletically inclined applicants were removed, the authors concluded, the racial complexion of America’s loftiest university would be significantly altered.

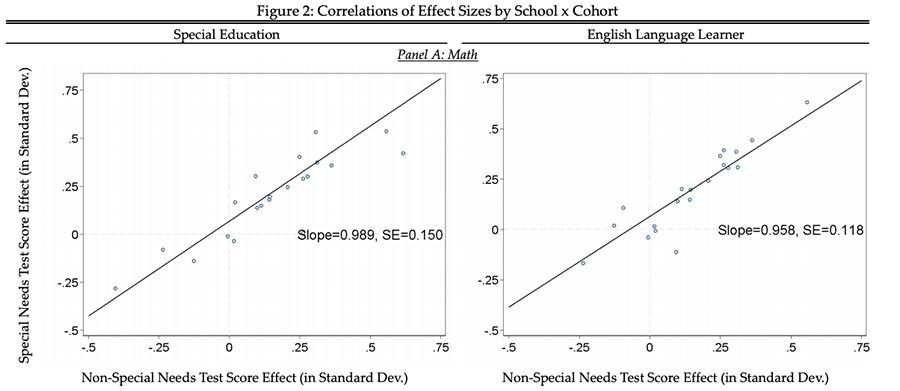

School Choice: Boston Charters Achieve Huge Learning Gains for English Language Learners & Special Needs Students

Charter schools in Boston are perhaps the best evidence that public school choice can work, boosting student learning more than any other charter sector in the country. Not only do their results compare favorably with charters elsewhere, they have dramatically expanded their enrollment over the past decade without any decline in performance.

The latest data pointing in their favor arrived this year, and it is perhaps the most impressive of all. According to a working paper by Tufts University economist Elizabeth Setren, Boston charters show substantial learning gains for special needs students and non-native English speakers, two of the populations facing the most severe learning challenges in all of K-12 education.

A year of charter school attendance in Boston significantly reduces achievement gaps for English language learners and special education students in both reading and math; even more notable, students of both classifications were more likely to be included in mainstream classrooms than their peers at district schools.

A combination of individual tutoring, increased instructional time and data-driven instruction is responsible for the positive results, Setren found, and the good news extends past test scores: Special needs students in Boston charter schools are four times as likely to graduate from a two-year college, and English language learners are roughly twice as likely to enroll in a four-year college. (Read more of our September coverage of this study on the impact of Boston’s charter schools)

Annals of Research: Value-Added May Be a Flawed Metric

The concept of teacher value-added is something like a golden key to education research — a single metric to capture the impact of an instructor on his or her students’ performance. With the wide array of data on academic achievement and postsecondary outcomes, both researchers and policy makers have become more ambitious about identifying teacher effectiveness.

But the idea has also long had its detractors. Within the research community, some have called to retire the term, arguing that it doesn’t measure in full the contributions of any instructor on the children under her care. And teachers themselves are largely opposed to the growing practice of linking decisions around compensation and hiring to statistical measures of teacher effectiveness.

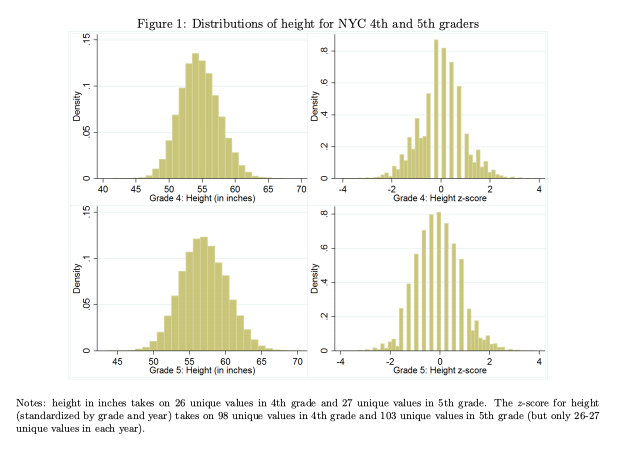

Now new doubts have arisen about the very premise. In a working paper released this fall, a group of academics found that, in the absence of research best practices, what looks like value-added effects could simply reflect statistical noise unrelated to actual teacher performance. Using data from New York City Schools, they find that the value-added impact of teachers on student height — which, obviously, they cannot impact — is roughly as large as on student performance on standardized tests. After scaling the models to account for sampling error, the team found that the “effect” on height disappeared; still the findings raise serious questions about the implementation of value-added models in research and policy contexts.

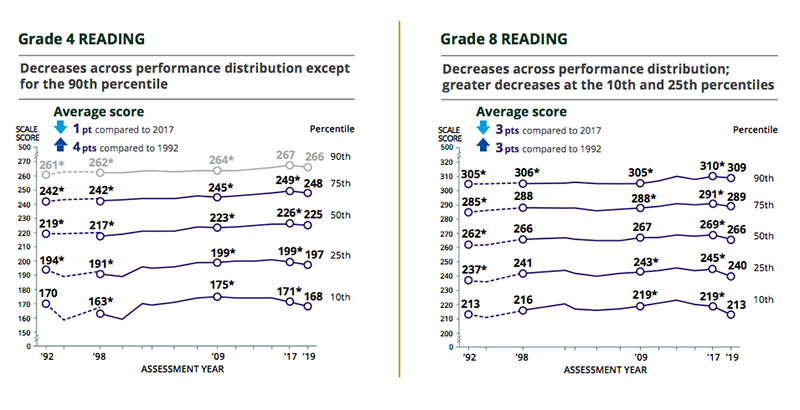

Testing: NAEP Offers ‘Disturbing’ Assessment

The National Assessment of Educational Progress — often referred to as “the nation’s report card” — has been the bearer of bad news for over a decade now. Since the end of the Bush administration, the biannual release of nationwide math and English scores for fourth- and eighth-graders has shown little or no progress for most students. Even worse, results have begun to diverge in recent rounds of testing, as scores for the lowest-performing students have declined faster than for other groups.

Scores in 2019 only gave more cause for concern, as scores dropped in reading and held steady in math. The number of fourth-graders testing proficient in reading fell by 2 percent since 2017, and performance sank for eighth-grade reading in an incredible 31 states. Alarmingly, students ranking in the lowest percentiles saw the worst drop-offs in the subject.

Only in two jurisdictions, Mississippi and Washington, D.C., did students see growth in at least three out of four subject-grade combinations. The continued lack of progress has experts sounding a downbeat note.

“We’re seeing our system challenged here in terms of realizing our children’s potential,” said Stanford University professor Thomas Dee. (Read more of our recent coverage of 2019’s NAEP results.)

Go Deeper: Get the latest ‘Big Picture’ installments, along with all our breaking coverage of education news and research, delivered straight to your inbox — sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter