Failing Schools: Home to Underachieving Students, Disillusioned Teachers and — According to a New Study — Higher Rates of Crime

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

The bogeyman haunting education reformers’ dreams has always been the “failure factory.”

You’re probably familiar with the term: a traditional public school that has performed dismally for years. Teachers are exhausted and disillusioned, and students’ academic promise is squandered amid crumbling infrastructure. Decades into its existence, the education reform movement is still focused almost overwhelmingly on improving or closing urban schools with poor academic results.

Now research shows that serially underperforming schools might not just be holding back students’ achievement; they seem to be driving higher rates of crime as well.

According to a study conducted by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, the closure of more than two dozen low-performing schools in Philadelphia led to a significant reduction in crime — particularly violent crime — both in the surrounding areas and throughout the city. The greater the number of students who left a given school, the greater the decline in crime rates, the authors found.

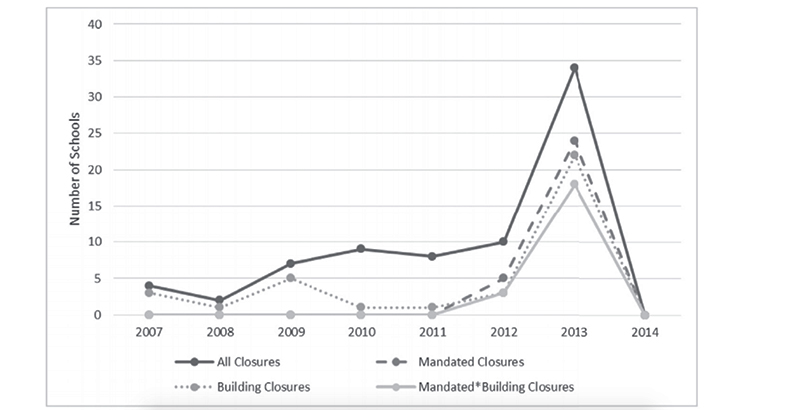

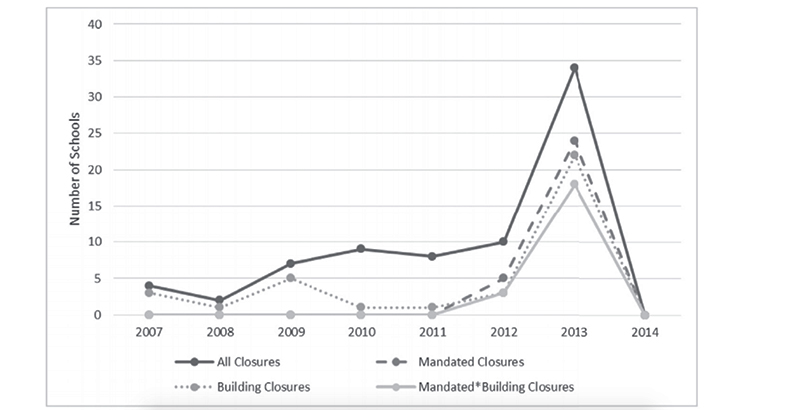

The study examines the two-year period between 2011 and 2013 when local authorities shuttered 29 public schools throughout Philadelphia, roughly 10 percent of all schools in the city. The decision was made by the School Reform Commission, a state-run panel created in 2001 to lead the school district out of its academic and financial challenges. The move was meant to address Philadelphia’s plummeting public school enrollment, and like many reforms undertaken before the district returned to local control last year, the closures proved controversial.

A study published this spring by education professor Matthew Steinberg and criminologist John MacDonald, both of UPenn, found that the academic effects of the closures were mixed — students displaced by closures typically saw learning gains if they were relocated to a high-performing school, while they also missed more days of school than they otherwise would have.

But the results of another study conducted by the duo, published this month in the journal Regional Science and Urban Economics and focused on the impact of closures on crime, were less ambiguous.

Using data from the Philadelphia Police Department, Steinberg and MacDonald found that in census blocks (the Census Bureau’s smallest geographic unit, often assembled together in block groups of roughly 1,500 people) where a school had been closed in the 2011-13 period, crime declined by 15 percent (roughly 1.4 incidences per month). Violent crime — defined as assaults, robberies, rapes or murders — declined by 30 percent (roughly 0.6 incidences per month).

The finding confirms what many would suspect. Research in criminology has long shown that rates of both criminal offending and victimization peak in the late teen years, when brain development hasn’t yet concluded and people are more prone to rash behavior. Previous research has shown that grouping together large numbers of young people, particularly those from low-income families, increases both the occurrence of crime and the likelihood that kids will get arrested together.

As prominent way stations for young people, K-12 schools satisfy several conditions for misconduct to flourish: They bring together hundreds of potential offenders and victims, both on campus and during the commute to and from school. Some existing studies have looked at the public safety impact of closing neighborhood Catholic schools or opening new charter schools, but in neither case did researchers examine the poorest and most at-risk children.

“What’s unique about this study is that we’re trying to understand the effect of the [targeted closure] policy,” Steinberg said in an interview. “The schools in Philadelphia that were targeted for closure, like schools in Chicago and other major districts that are doing these targeted school closings … were the most under-enrolled, which typically serve the lowest-achieving kids or the highest-poverty kids.”

Examining data from the Pennsylvania Department of Education, the authors found that the closed schools served predominantly black students and those eligible for free- or reduced-price lunch, a leading indicator of poverty. The same figures showed that the schools were characterized by relatively high numbers of arrests, suspensions and truancy, as well as poor academic performance in both math and reading.

The downtick in criminality was observed during a time when Philadelphia was seeing across-the-board declines in violent crime, including a 25 percent drop in homicides. Steinberg pointed to signs that the school closures played a clear role in making city streets safer: The decrease in offenses was observed during school hours, when kids would otherwise have been there, but not during weekends; further, the census blocks from which the greatest number of students were displaced saw the largest reductions in crime.

Measured against census blocks where schools did not close, or where schools were not located in the first place, the sharp reduction in misconduct is evident; the effects also stand out amid multiple separate time periods (2006-13, 2008-13, 2009-14, and 2010-14), Steinberg noted, meaning that the study wasn’t simply drawing on one or two years in which lower crime was observed.

“I think it’s very safe, frankly, to say that closing schools caused a reduction in crime in these neighborhoods,” he said. The cause, he said, was the dilution of disadvantaged populations “by removing, shifting a population of kids who were much lower-achieving and much lower-income than the typical kids in Philadelphia.”

The effects on crime were especially pronounced in areas where underperforming high schools were closed. Census blocks that experienced a district-mandated high school closure saw an impressive 40 percent reduction in violent crime, while elementary or middle school closures were associated with an 18 percent reduction.

Perhaps most promisingly, the data collected by Steinberg and MacDonald don’t seem to indicate that criminal behavior simply migrated elsewhere after the closures took effect; census blocks neighboring those where schools were shuttered experienced no resultant spike in violence, and in fact benefited from a 10 percent decline in property crime. Across the entire city of Philadelphia, the authors estimate that the 2011-13 school closures led to a 2.3 percent drop in violent crime and a 5.3 percent drop in property crime.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)