Big Improvements Require Big Changes: Close Bad Schools and Expand Good Ones

Aldeman: New Orleans, Denver & Florida show how implementing a portfolio model of school choice can lead to dramatic academic gains.

Close low-performing, underenrolled schools. Expand high-performing, in-demand schools.

This formula has tremendous upside. It’s what cities like New Orleans, Denver and Indianapolis have done to great success. It’s also been a key ingredient behind Florida’s climb up the state achievement rankings.

Over the past two decades, Florida has added about 230,000 students, closed 214 schools and added 1,011 new ones. This churn has undoubtedly forced some hard decisions at the local level, but it has also improved the overall quality of schools statewide.

Last year, for instance, Florida gave 1,299 of 3,451 public schools an A on their state report card. Of those A-rated schools, 192 didn’t exist 10 years ago, and 483 didn’t exist 20 years ago. Last year, 47% of schools that predated 2004 received an A or B, compared with 69% of those that have opened since then.

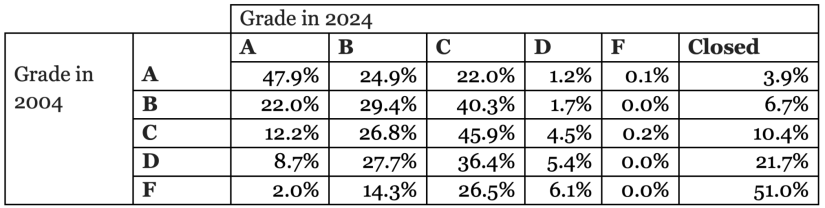

The table below looks at the data in a slightly different way. It compares the performance of schools that existed in 2004 with how they did in 2024. Among schools that received an A in 2004, nearly half still earned top marks last year, and another 25% earned a B. For the most part, good schools tended to stay good.

But look at the bottom end. Among schools that earned an F in 2004, only 2% received an A in 2024. In fact, more than half the F-rated schools in 2004 had been closed by last year. In Florida, schools either got better or they shut down.

Table: Florida Schools Got Better — or Were Closed

This combination of opening more schools while closing underperforming ones can be hard to execute. And even when a school is underenrolled or underperforming, closing it can be disruptive. Some advocates and politicians have used those disruptions to argue that all this school choice and markets stuff of the past two decades is too much trouble, and that education policy should just stick with trying to improve existing neighborhood schools.

That might seem logical, but the evidence against school turnarounds has slowly changed my mind. For one thing, research around the No Child Left Behind law found that light-touch interventions like writing a school improvement plan did little to change the trajectory of chronically underperforming schools. Big improvements required big changes.

Dramatic improvements are possible. Right now, for example, the Houston school district is making impressive gains thanks to the leadership of hard-charging superintendent Mike Miles. Lawrence, Massachusetts, is another case where a state takeover helped raise student achievement.

But these success stories are not the norm. Massachusetts, for example, has been unable to replicate the Lawrence success story in other cities, and a broader review of state takeovers found they had no effect, on average. Similarly, Tennessee’s Achievement School District, which had charter management organizations take over chronically low-performing district schools, did not improve scores on middle school assessments, ACT college admissions tests or end-of-course exams.

In other words, it’s hard to make bad schools better. Not impossible, but very hard.

So what is Florida doing differently? It follows the portfolio model, which focuses on developing a comprehensive set of high-quality and autonomous public schools. These are evaluated based on their performance and parent demand, and policymakers concentrate on cultivating a broad variety of high-quality options for families.

This approach has contributed to citywide transformations in places like Denver and New Orleans. For example, Tulane University’s Doug Harris and a team of researchers found that New Orleans students made large gains in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, and that the average new school was almost always better than the average school that was closed or taken over. It was this effect — of closing lower-performing schools and replacing them with better-performing ones —that drove the citywide gains.

A comprehensive report from the Center for Education Policy Analysis at the University of Colorado Denver found that Denver’s portfolio strategy also produced large gains. Thanks to a common regulatory framework, annual evaluations of school performance, the closure of low-performing schools, the creation of new schools and district-led turnaround efforts, Denver’s performance rose from the bottom fifth percentile of all districts statewide to the 60th percentile in English Language Arts and the 63rd in math.

The portfolio model is far from a panacea. It requires districts to take a more active role in helping parents make good choices among their options, and for city leaders to tackle thorny policy questions around transportation and students with special needs. The politics can also be hard, and localized interests tend to protect their school no matter how few students want to go there. One extreme example: a Chicago school with 28 students operating with 27 employees.

Political pushback against school closures led Chicago to adopt a moratorium on school closures and for Denver to retreat from its successful portfolio model. But these trends are also playing out in smaller ways in many parts of the country. As I noted last year, school shutdowns have been falling to modern lows, even amid widespread enrollment declines.

Yet, keeping underenrolled schools open carries steep financial costs, which can then be used as an argument against investing in other, more popular schools. And when districts pursue this scarcity mindset, they end up forcing parents to fight over whose kids get into the “good” schools. In Fairfax County, Virginia, where I live, the district has tinkered with the entry requirements for the Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, a selective magnet school, but has not created another one. New York City has similar fights over its specialized high schools, although several mayoral candidates — including charter school donor Whitney Tilson, Comptroller Brad Lander and state Sen. Jessica Ramos — called for creating more of them.

The same trends are playing out in Massachusetts, where Democrats mostly vote against expanding charter schools even as the state’s charter sector consistently demonstrates impressive outcomes. (In fact, the research on high-performing charter networks has been possible only because they are so oversubscribed that they have to conduct random lotteries to see which kids get in!) And in Boston, the Metco program, a voluntary desegregation initiative that has produced amazing results for students since the late 1970s, still has only enough seats for half the kids who want one.

But won’t expanding school choice options harm existing schools? Surprisingly, that fear hasn’t been borne out in the data. In fact, EdChoice has found that schools with enrollment declines tend to receive more money thanks to various funding protections, and a bevy of research has found that competition forces existing schools to respond in ways that boost student achievement.

The portfolio model is certainly not the only way to improve school quality, but it is a particularly good fit for the current moment. As parents clamor for more choices, education policymakers should focus on providing a high-quality portfolio of options for them to choose from.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)