Interactive: In Many Schools, Declines in Student Enrollment are Here to Stay

Aldeman: Districts with the steepest drops can't escape the financial pressures that come with serving fewer kids. See what's happening in your state

By Chad Aldeman | April 29, 2024

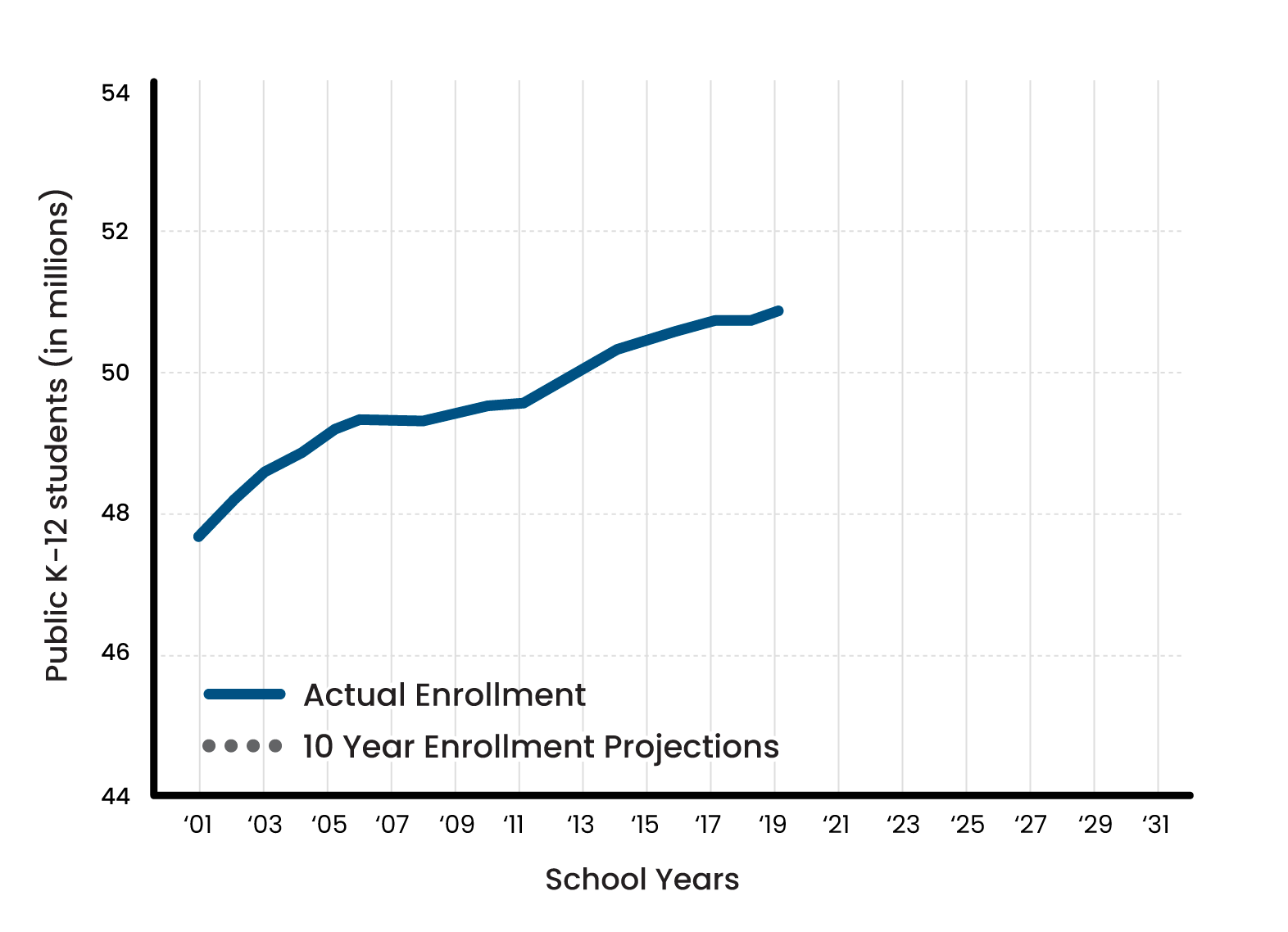

Public school enrollment rose steadily throughout the first two decades of the 2000s.

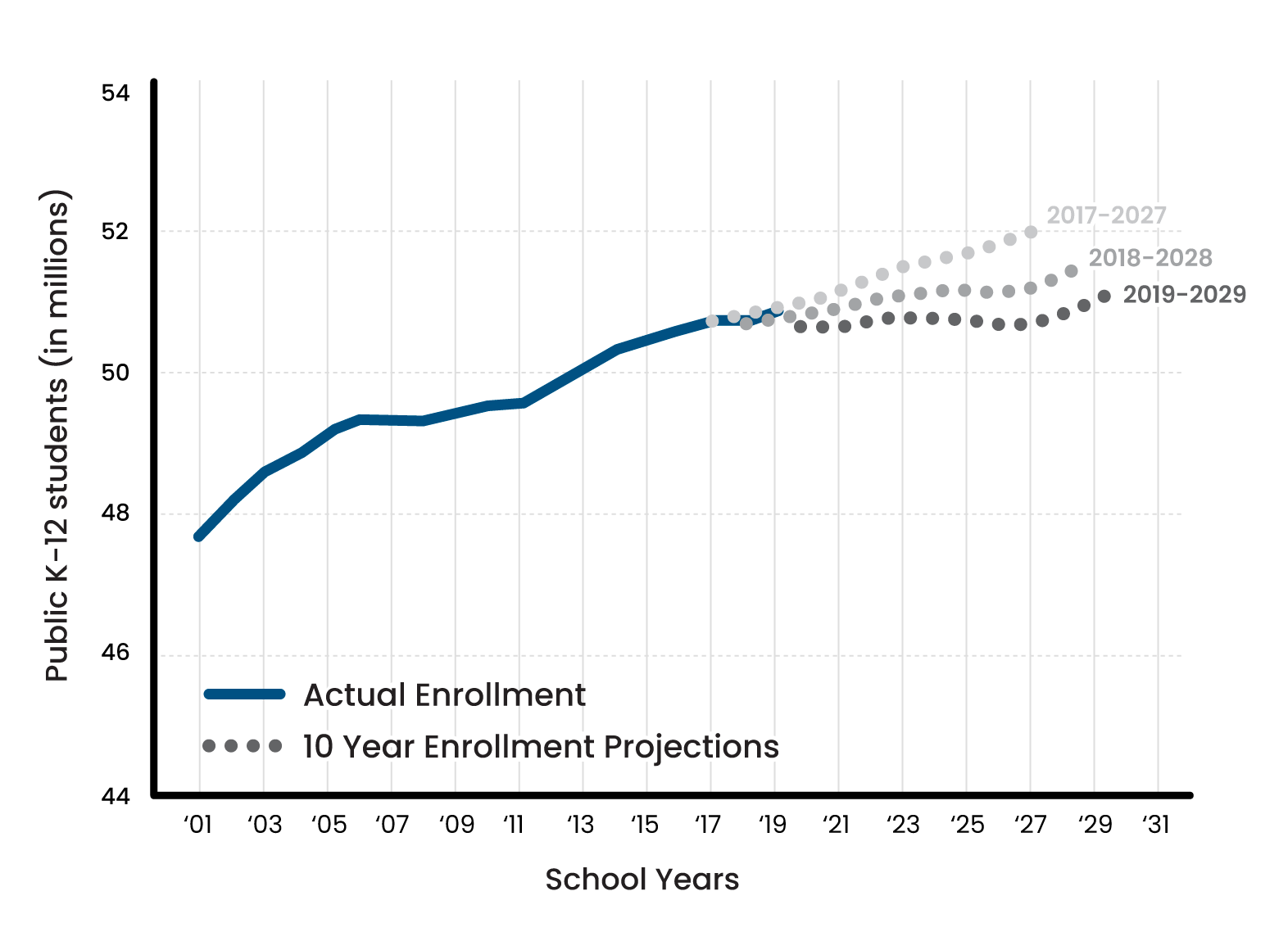

The National Center for Education Statistics was projecting public school enrollments to continue to grow, although its future projections were becoming less optimistic, thanks to falling immigration and birth rates.

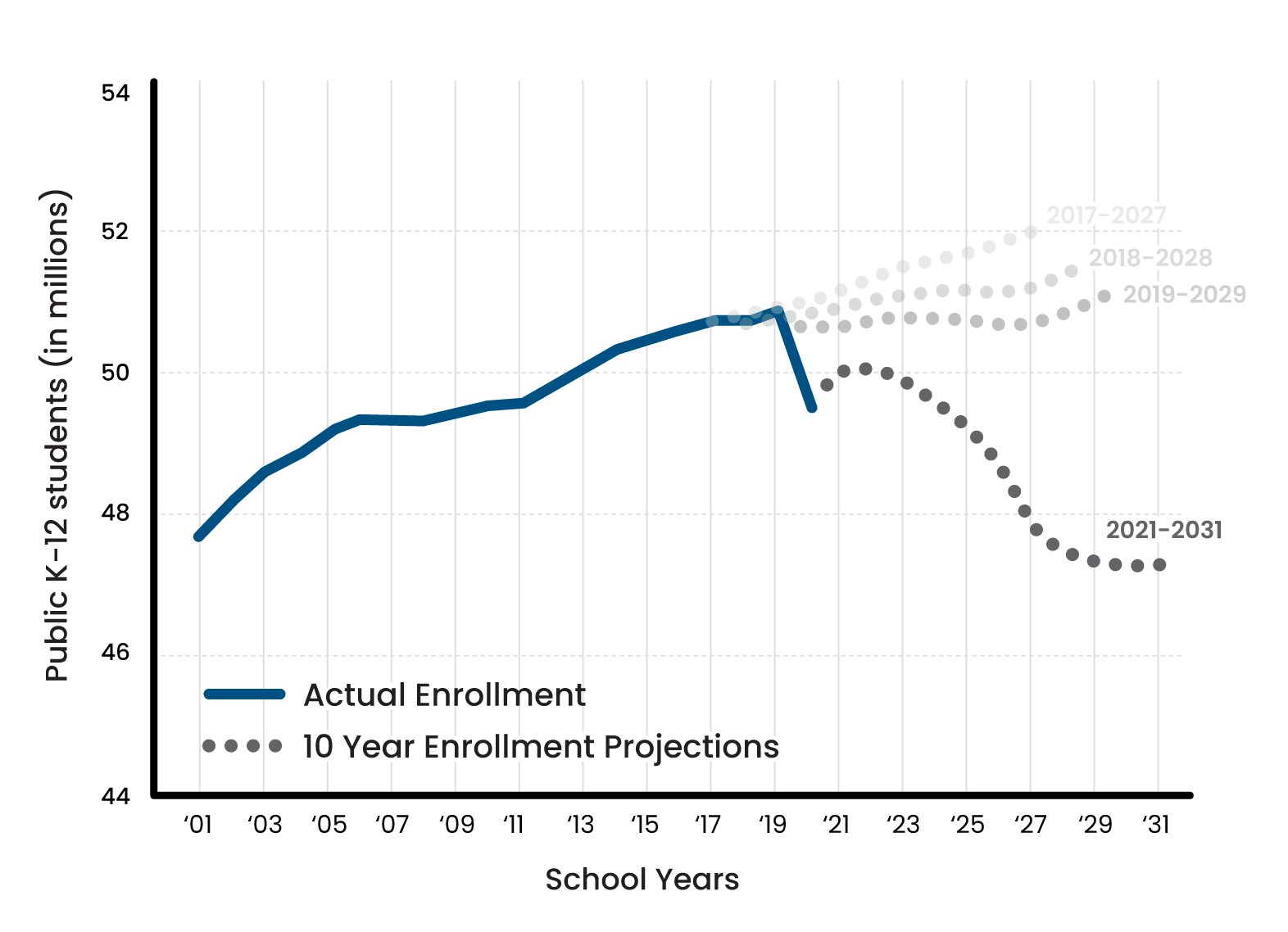

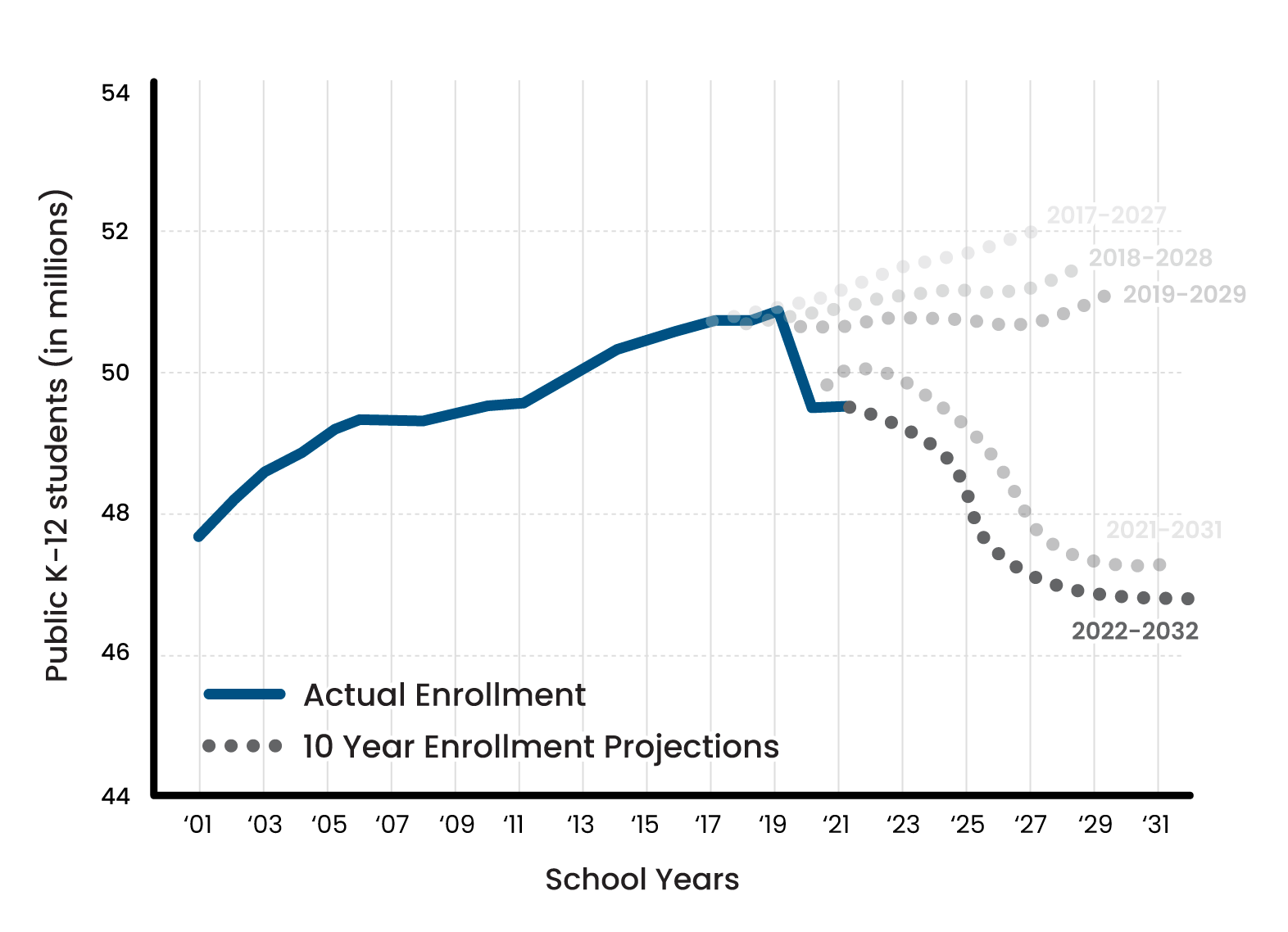

When COVID-19 hit, enrollments took an immediate dive, and the center lowered its forecast. It now projected a short-term bounceback followed by a longer-term decline.

The immediate, sharp rebound didn’t happen. The center is now projecting much lower enrollments for the rest of the decade.

According to the center’s most recent data, public schools served 1.2 million fewer students in 2022-23 than they did in the last year before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The losses were widespread, with 37 states and two-thirds of school districts suffering a decline. California was the biggest loser in numeric terms, with 420,000 fewer public school students (a 6.7% decline), while Oregon suffered the biggest decline in percentage terms (9.4%).

What caused these trends? As Stanford University researcher Thomas Dee has documented, the COVID-era enrollment declines were due to a combination of factors — a rise in homeschooling, a shift to private schools, fewer school-age children and some students who simply went missing from the data.

But that’s the past. A separate division of the center is in charge of making forward-looking projections, and it has more grim news: It projects that public schools, including public charter schools, will lose an additional 2.4 million students (4.9%) by 2031.

Those projections are based on a mix of historical enrollment patterns and demographic assumptions, and it’s possible they will be too pessimistic, especially given the uncertainty of the last few years. For example, homeschooling numbers surged in the early years of COVID but have started to come back down in most places. Similarly, immigration took a dramatic nosedive in 2020 but has rebounded since then.

Birth rates, however, are a major driver of student enrollment trends, and they have been in a multi-decade decline. Birth rates also bounced around during COVID, but in a piece for Brookings, Melissa Kearney and Phillip Levine found that the trajectory is once again downward. To put it in concrete terms, they point to data showing that there were almost 600,000 fewer births in 2019 than in 2007. That means 600,000 fewer kindergartners showing up to schoolhouse doors next fall.

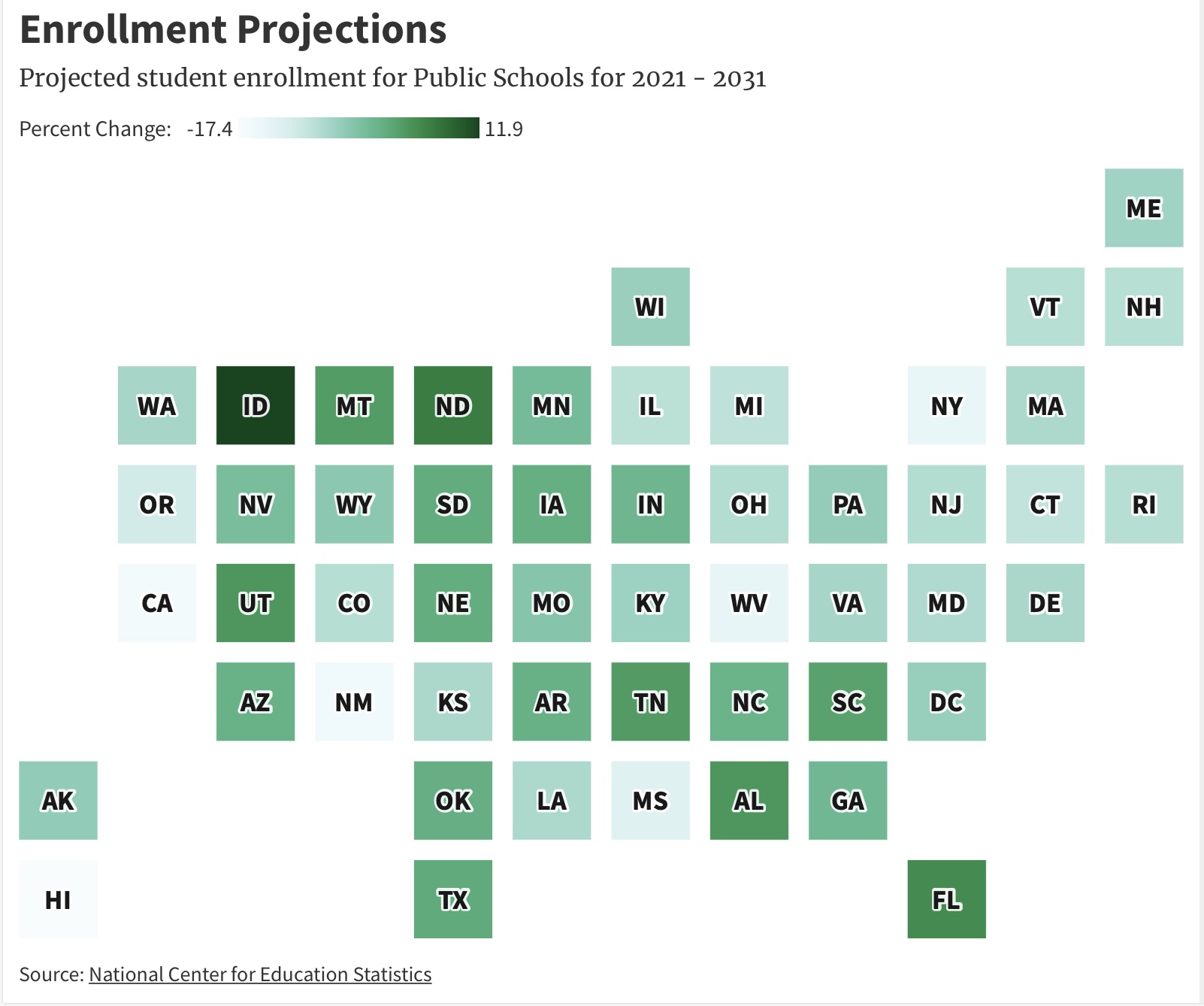

The enrollment changes are not spread evenly across the country. Thirteen states — including Florida, North Dakota and Idaho — are projected to gain students by the end of the decade. But that means the rest of the country should brace for fewer students. Seven states — Hawaii, California, New Mexico, New York, West Virginia, Mississippi and Oregon — are all projected to suffer double-digit declines in addition to any losses they’ve already seen. California alone is projected to lose nearly 1 million public school students by 2031.

In general, districts receive money based on how many students they serve, so shrinking communities should expect smaller school budgets going forward. It’s not a 1:1 relationship because most districts will still be able to count on local funds, which are typically not tied to student enrollment, as most state funds are. That protects about 45% of school district revenues for the average district. Similarly, states have a variety of hold-harmless provisions that offer at least temporary financial protection for districts with declining enrollment.

Still, those districts will eventually have to get by with lower revenues. That’s a hard transition to make, especially as they shoulder growing pension costs plus fixed expenses like bond or facilities payments.

The one-time federal relief funds gave a temporary lifeline to districts that were operating beyond their means, and it allowed schools across the country to reduce their student:teacher ratios. But when the money expires later this year, districts will have to consider options for downsizing their budgets, whether that means closing underenrolled schools, laying off staff to get back to their pre-pandemic levels or scaling back promising programs that are only just beginning to show results.

In other words, districts with the steepest enrollment declines won’t be able to escape the mathematical pressures that will come with serving fewer students. Further enrollment declines are coming in most parts of the country, and districts must be prepared to navigate those headwinds.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter