Investigation: In NYC School Where a Teenager Was Killed, Students & Educators Say Lax Discipline Led to Bullying, Chaos, and Death

Updated June 13

An unnamed boy stands in the stairwell of his New York City high school. He secures one end of his sweater to the rail, ties the other around his neck, and tries to hang himself.

The boy had been bullied mercilessly for being gay, and nothing changed no matter how many times he or his grandmother asked administrators for help. He just wanted it to end. But just then, according to The New York Times, “a vice principal and two students happened by” and saved him.

Teachers and students say the Times story was inaccurate and incomplete. The assistant principal was not there, they say, and the two students who intervened deserve to be named: Ariane Laboy, 16, and Matthew McCree, 15.

But the public was not introduced to Laboy and McCree for the life they saved that day. We know their names because six months later, on Sept. 27, 2017, someone in history class threw a paper ball at Abel Cedeno, an 18-year-old sophomore who, like the unnamed student in the stairwell, had been bullied for his sexuality. The profanity-laced challenge and invitation to violence that followed were par for the course at the school. The one thing different that day: Cedeno pulled out a switchblade. He stabbed McCree, and when Laboy came to McCree’s aid, Cedeno turned the blade on him. Laboy fell into a coma for two days. When he awoke, he asked for an egg roll and news of his best friend.

McCree was dead.

McCree’s death at the Urban Assembly School for Wildlife Conservation was the first in New York City schools in decades. The incident initially received substantial media coverage, focusing particularly on homophobia and unaddressed bullying at the school. Cedeno gave an interview saying that he regularly felt physically unsafe and just snapped after being incessantly bullied, and that he acted in self-defense after McCree had attacked him in history class that day. With these issues introduced but not resolved, and Cedeno’s manslaughter case slowly working its way through the court system, McCree’s death faded from the headlines and the public consciousness.

But McCree’s teachers and friends say the media missed the real story by describing UA Wildlife as having been on a “downward slide” but not digging into what was really going on at the school. “If this were Parkland, the media would have never stopped asking why,” said Christopher Vasquez, who taught McCree earth science at UA Wildlife. “But they painted it like he was the bully, like he was a thug. Fit it to their stereotypes and forgot about it.”

Two months after McCree’s death, Robert Pondiscio and I wrote a column in the New York Daily News asking whether UA Wildlife’s shift in discipline policy played a role in the tragedy. I’d done research and writing (and have since given testimony to the House Judiciary Committee and U.S. Commission on Civil Rights) about the unintended consequences and dangers of discipline reform, and suspected that those reforms were part of the story here. Several education writers scoffed (and Tweeted objections). But Vasquez reached out to me to tell me that they were.

Vasquez connected me with eight of McCree’s teachers and six of his friends. Friends and teachers said he was not a bully but a very “respectful kid” and “wicked smart.” Aside from Vasquez, who no longer teaches in New York City, only one other educator, former teacher and assistant principal Cynthia Turnquest-Jones, agreed to be quoted by name. The rest asked to be quoted using pseudonyms, fearing retaliation. Some are still at the school, others teach elsewhere in the city, and one works outside the district; several lack tenure, and all believe they’d be targeted for bad evaluations if they spoke out publicly. Some have filed lawsuits or grievances against the district for matters stemming from the incident and subsequent administrative actions.

The New York City Department of Education replied to some initial queries for this investigation but did not respond to any further emails. The Urban Assembly nonprofit and the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators, which represents principals and assistant principals, declined to comment. School administrators criticized by the teachers did not respond to repeated requests by email and phone for comment.

One student, who has transferred out of UA Wildlife, agreed to be quoted by name. Students and teachers said they wanted to set the record straight on McCree as well as on UA Wildlife, a once safe and supportive school that fell into chaos as new administrators implemented a supposedly more positive approach to school discipline.

This change was in line with New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s campaign promise of putting city schools at the vanguard of a nationwide movement to unwind traditional discipline in favor of a new progressive, or restorative, approach. At UA Wildlife, meaningful consequences for misbehavior were eliminated, alternative approaches failed, and administrators responded to a rising tide of disorder and violence by sweeping the evidence under the rug, students and teachers said. If they had prioritized student safety over statistics, McCree’s teachers believe, he would still be alive. And they fear that the dynamics that destroyed UA Wildlife are playing out across New York City.

Before the Fall

UA Wildlife, which serves approximately 450 students in grades 6 to 12, was founded in the Bronx in 2007 as a traditional district school with support from the Urban Assembly nonprofit. As recently as five years ago, under the leadership of founding principal Mark Ossenheimer, it was a thriving school with engaged students and a passionate faculty. According to the 2013-14 NYC School Survey, 86 percent of teachers said order and discipline were maintained and 80 percent of students said they felt safe in the hallway.

A senior whom I’m calling Jeremy recalled that “sixth to eighth grade was honestly the best school years of my life. We had the best staff [and] the best students.” A former humanities teacher whom I’m calling Ms. Smith said, “The students respected us, they cared for us. They knew we cared for them. It was a very family environment.” There wasn’t a trace of the homophobia to come. According to a former humanities teacher whom I’m calling Ms. Hernandez, “Kids who were transgender or gay or lesbian were comfortable. It wasn’t a thing.”

But by the 2016-17 school year, Smith and most of the old faculty had fled. Only 19 percent of teachers said order was maintained and only 55 percent of students said they felt safe. Rumors of weapons were omnipresent, and fights were a matter of weekly, if not daily, routine.

How did conditions deteriorate so quickly?

Back in the 2013-14 school year, the dean, Hector Diaz, commanded the respect of the students. “He was strict, ex-military. He would take no crap from them,” said Hernandez. Jeremy said, “Mr. Diaz was a strict person indeed, but he was also a caring dean. Nobody would mess around when he was dean ’cause they realized the consequences were not good.” And Diaz “didn’t even have to suspend” very much, Hernandez said, because the kids knew he meant business and whenever they were suspended, they “were like, ‘Nah, I don’t want to be out again, I don’t want to do that again.’ ”

Most teachers think the same way as Hernandez about discipline; in Philadelphia, more than 80 percent believe suspensions are essential to ensuring a safe environment and encouraging students to follow the rules. In Oklahoma City, two-thirds of teachers say they need greater enforcement of traditional school discipline to be effective in the classroom. But in Oklahoma City, Philadelphia, and New York, principals — under orders from central office bureaucrats — told teachers that they’re wrong, that traditional discipline is racially biased and must be phased out in favor of the new restorative approach. Teacher polls show a widespread lack of confidence in this system. At UA Wildlife, it was a fatal failure.

Descent Into Disorder

Under de Blasio, the NYC Department of Education began requiring that teachers provide full documentation of a range of nonpunitive interventions to at least three mid-level infractions before asking their principal to issue a suspension. Principals, in turn, had to apply in writing to a central office that often rejected their requests. At first, UA Wildlife resisted the shift. Hernandez recalled that when the central office started “kicking suspensions back,” the “dean was, like, ‘This is what I have to do, and I’ll do it,’ ” and he fought to push them through.

But in the 2014-15 school year, a new leader, Latir Primus, took the helm. A probationary principal, Primus was under pressure to meet the expectation of his superiors, and, as Hernandez recalled, “when the superintendent was, like, ‘I don’t want the suspension rates,’ ” Primus followed orders. He boasted in UA Wildlife’s comprehensive education plan that the “school has low incidents of behavioral problems as evident in their suspension data.” But lower suspension data can be quite easily achieved by simply not enforcing rules.

As Hernandez said, “It comes down to rules. Where’s your line? Kids know where the line is. It was a free-for-all.” In Primus’s first year, she said, the “kids ruled.” There were “things that you were surprised to see because those were the kids in sixth grade who didn’t do that. Then their behavior changed.” A current UA Wildlife student whom I’ll call Deon agreed. “The school changed, because [a] situation would be handled right away before the new people came,” but “now, they just brush it off like nothing,” he said.

When Vasquez, the earth science teacher, told one student to get off the phone or else see Vice Principal Daniel Pichardo, the student left class and returned to announce, “Pichardo says it’s OK I can stay on my phone,” Vasquez said. “How are you going to tell me that I need to write rules, then the second I try to enforce those rules, you take away my credibility?” (Pichardo did not respond to repeated requests for comment by email and phone.)

But in this instance, it was actually Vasquez who broke the school rules by trying to bypass the “referral ladder” in its staff handbook that UA Wildlife had established in compliance with district directives. Under this process, according to a current humanities teacher I’m calling Mr. Newman, “It would probably take 50 steps before a problem was to actually come before an administrator.”

If that sounds like an exaggeration, it’s not much of one. According to the handbook, before referring a student to the dean, “the following documentation must be included: Student Misconduct Form, Family Telephone Log, Intervention Log, Witness Statements.” Pichardo should have been the fifth recourse: The staff handbook “defines the order in which staff should address these issues: 1. Teacher, Student; 2. Teacher, Student, Advisor (Dean If Appropriate); 3. Advisor, Dean, Parent, Student; 4. Guidance Counselor, Dean, Parent, Student (In Certain Cases); 5. Assistant Principal, Parent, Student; 6. Principal, Parent, Student.”

Furthermore, “Before any referral is made, the teacher should have followed the step [sic] below: Intervention Strategies, Conference with Students, Warnings, Called parent/guardian, Conference with parent/guardian.” For all these matters, “teachers MUST have the appropriate documentation. Teachers should be keeping anecdotal [records] on a regular basis, telephone logs, parental conference logs, intervention forms, and all other relevant documentation.”

The kids quickly realized that their teachers could get into trouble for getting them into trouble. In a video shot by Vasquez in his classroom that was viewed by The 74, two girls are standing in front of the class, talking loudly. When he asks them to return to their seats, one girl yells, “I’m gonna stand right here! You not tellin’ me nothing! Mr. Primus not tellin’ me nothing! None of them teachers tellin’ me nothing! So I’m gonna stand right there!” The other girl chimes in, “I’ll take you to court!”

“As teachers, policymakers have made it so we have no authority,” explained a former humanities teacher I’m calling Mr. Sidney. “Only perceived authority. Only as much power as you get your kids to believe. Once the kid finds out he can say ‘F*** you,’ flip over a table, and he won’t get suspended, that’s that.”

The Restorative Approach Fails

In addition to disregarding disciplinary complaints, Primus instituted a restorative approach, which he later codified in the School Comprehensive Educational Plan, informing district leaders that he “focused on creating a culture of learning by instituting a Restorative Practices approach to school discipline.” In major urban districts across the country, teacher polling suggests this new approach doesn’t work. At UA Wildlife, the restorative approach accelerated the school’s disintegration. “Instead of suspending the kids, they made this group called the Warriors,” said Hernandez. “It was all the kids that needed discipline, and they did this social justice program and it kind of backfired on them.”

Rather than being punished for bad behavior, the Warriors were rewarded for good behavior: given special attention, personal lunches, and 15-minute passes to leave class to “de-stress,” several of the teachers said. The students used this last perk as an excuse to cut class, and this all started making well-behaved students resentful. Smith, the former humanities teacher, said that other students started thinking, “I did everything right. Why am I not getting special privileges?” Explained Hernandez, “You had some really smart, good kids in that school and they thought, ‘Look, I can be bad and get rewarded.’ ”

Midway through the year, the school discontinued the failed Warriors program. Then it phased in a new Positive Behavioral Intervention System, offering students tickets redeemable for prizes in exchange for good behavior. “But the students didn’t value them,” said Vasquez, “so that system failed as well.” He explained that after each failure, administrators blamed teachers for not implementing the system correctly. “The worst and biggest waste of time was advisory lessons on how to be responsible,” he said. “Making posters around the school like, ‘Take off your headphones.’ None of the students took that seriously because they knew no one could follow through.”

No one could follow through because administrators received documentation of behavioral problems but didn’t act on it. The staff handbook directed teachers to enter anecdotal logs of good and bad behavior in Skedula, the school’s student tracking software system. Under Ossenheimer, the founding principal, and Diaz, the no-nonsense dean, a negative anecdotal would prompt assistance. But under the new leadership, according to Newman, “If you put something under negative, it would be there but no one would respond to it. … We didn’t know if they were remedying it or completely ignoring it.” (Primus did not respond to repeated requests for comment by phone and email.)

Turnquest-Jones, who served as assistant principal under Primus, is still a strong believer in a positive approach. She noted that in a high-poverty school where students don’t necessarily get positive reinforcement at home, “rewards work very, very well.” However, she said, “when you’re rewarding children, there’s also a certain tone where students accept being corrected. With accepting being corrected, it’s all about consistency. So once the consistency changed, then the ability to correct changed, then the ability to correct and reward changed.”

From Dangerous to Deadly

Turnquest-Jones believes the school struck a reasonable and consistent balance under Primus’s leadership. Meanwhile, teacher opinion on Primus was mixed; some faulted him for failing to enforce rules, while others noted that he maintained a positive personal presence in the hallway and took an active interest in students’ lives. But midway through the 2015-16 school year, Primus was replaced as principal by Astrid Jacobo, about whom no one had a kind word to offer.

“If I could rewind, I would 10 times work under Primus again,” Vasquez said. “We had big discipline problems. But with Jacobo, everything was just clear chaos.”

“I remember one time, this was right when she started,” said a former STEM teacher I’m calling Mr. Garcia. “There was one student who was cursing in the hallway. Jacobo comes up very calmly, puts her hand on her shoulder, and says, ‘We don’t curse in this school.’ The girl yanked her shoulder away saying, ‘Get off me, bitch.’ She did that. Fine. What’s the result? Nothing. She didn’t get detention. Nothing.”

Because of that incident and others like it, according to Jeremy, “Nobody listened to Jacobo. She would threaten us at first with detention or suspension, and she wouldn’t do it. This caused students to ignore her.” Turnquest-Jones, who was assistant principal in Jacobo’s first year, recalled that students “cussed Miss Jacobo out from head to toe” without consequence.

But if Jacobo was passive toward students, she was aggressive toward teachers. “When she arrived,” said Smith, “we were all rated ineffective” by Jacobo on their teacher evaluations. That is somewhat of an overstatement, but the data confirm a sharp uptick in negative evaluations. In the 2015-16 School Comprehensive Educational Plan, 86 percent of teachers were rated effective. The following school year, the plan reported, “58 percent of teachers were rated developing/ineffective on Designing Coherent Instruction, and 71 percent were developing/ineffective on Engaging Students in Learning.” Several teachers could only speculate that Jacobo was pursuing personal vendettas. But Turnquest-Jones, who is African-American, said she believes Jacobo was motivated by racism.

She recalled that the day after Primus left, District Superintendent Rafaela Espinal and Jacobo came to tour the school alongside Turnquest-Jones, who was assistant principal at the time. “While we’re walking room from room together, the superintendent makes a comment about why are there so many white teachers in our school teaching our students. Ms. Jacobo responded to her, but she responded to her in Spanish,” shutting Turnquest-Jones out of the conversation — a practice that she said became standard. The student body is 24 percent black and 71 percent Hispanic, and Turnquest-Jones told me the teaching force became more Hispanic as turnover increased. (Espinal has previously faced legal action alleging racial discrimination and retaliation.)

Whereas several teachers faulted Primus for not dealing with negative anecdotals, one accused Jacobo of actually erasing them, even when a teacher’s job was on the line. A current teacher whom I’m calling Mr. Martinez told me about a student who once assaulted him and told him he planned on getting a teacher fired someday. Several years later, this student accused a teacher of assault. Martinez told his colleague not to worry, because the old anecdotal would clear up the matter. But when he looked, Martinez said, his positive logs for that student still existed, but the negative logs were no longer there. (Jacobo did not respond to repeated requests for comment by phone and email.)

Faced with increasingly unruly students and a hostile administration, teachers fled. Smith recalled, “Either that year or the year after, I would say about 80 percent of the teachers are gone. Maybe even more. Mass exodus. That also plays into the whole discipline thing. You took out the experienced teachers that could control those kids.” Students, like Jeremy, were distraught that “Jacobo started to get rid of teachers and hire teachers that really didn’t care about us.”

The new teachers received essentially no support from the administration on student behavior. They could turn to Dean Matthew Lawlor, but Sidney, the former humanities teacher, recalled that Jacobo literally locked Lawlor out of meetings. Some teachers stopped recording misbehavior on Skedula, seeing no point. Others continued, hoping against hope for support that never came. The following logs, from the 2016-17 school year, give a flavor of daily life at UA Wildlife:

● Log 14873: “Today [name redacted] came into my class during a class that wasn’t his and smacked me in my face very hard.”

● Log 17136: “[Name redacted] and [name redacted] came in to my 3rd period English class and when I closed the door to have them leave [name redacted] stated ‘I’m gonna knock you out one day!’ ”

● Log 18220: “When I went to change the power point [name redacted] told me to not change ‘the f***ing slide’ and that is [sic] I did change the f***ing slide she would ‘f***ing slap me on the side of my f***ing head.’ ”

● Log 17119: “[Name redacted] was asked to put away his phone and do his work. He then proceeded to threaten Rudolph and myself. He informed us that we were ‘c***-sucking assholes’ and that I will beat the f*** out of you two on the last day of school. Threats should not be tolerated. I will attempt a parent call. Prior calls have not worked.”

● Log 17988: “I was sitting in 403 6th period with Mr. Anderson, when [Name Redacted] walked in uninvited and told us he ‘was going to kill us both,’ furthermore he said, ‘who am I going to kill first.’ He then grabbed an empty bottle out of the garbage and threw it across the room. He subsequently left.”

But to the teachers, one log stands out above all others: Abel Cedeno’s mother called the school in 2014 to warn that he might start bringing a knife. Smith recalled, “At the time, they looked through his bag and didn’t find anything. That’s all they did. They searched his bag. They didn’t find the knife. That was it.”

Cedeno’s attendance for the next few years was spotty. He was “left behind,” according to a former STEM teacher whom I’m calling Mr. Charles, who recalled that Cedeno was “not a bad kid. He was a very good kid, actually,” but he encountered more homophobic bullying as the school declined into chaos. Charles said Cedeno’s mother complained to administrators, but they “deliberately ignored the warning because [they] wanted to show that everything was going OK. But it wasn’t.”

As for McCree, his middle school teachers recalled him being a “wicked smart” and “respectful” student, though a bit of a “prankster.” But by the time he reached high school, intelligence and respectfulness had gone out of style at UA Wildlife. His friends insisted that he was not a homophobe or a bully. But a high school teacher recalled him as an instigator. “He and Ariane [Laboy] would be messing with kids and starting things,” said Sidney. “I told him to stop picking fights, because someday he could pick one with someone who just didn’t care.”

On Sept. 27, 2017, Cedeno brought a knife to school. He stood up and began walking out of history class, and here’s what happened next, according to a classmate and friend of McCree’s whom I’m calling Molly:

So, um, he was going to leave the room and they threw a paper ball in his direction. I guess to go in the garbage, and it almost hit him or it hit him. And he turned around and he was like, ‘Who the f*** threw that?’ Right? So, Alex says, ‘I did it.’ But then Matthew stands up and he’s like, ‘I did it.’ Right? And um, and [Abel] goes, ‘All of y’all in the back are pussies.’ So Matthew starts coming around. Mr. Jacoby tries to push him back, he’s like, ‘No, you don’t have to do…’ Then, Matthew like just literally passes right by Mr. Jacoby and starts going toward him. That was when Abel pulls out the black switchblade and he was like, um, ‘Pull up, run up, run up.’ Right? Then, um, Matthew. I don’t know if he saw it or not. But as soon as everybody saw it in the front, they started backing up. And we were like screaming, ‘Matthew, don’t do it!’ And, um, he still kept going. He landed mad hits on him. And then that was when he got stabbed. And he, it looked like Abel, was just punching him in the stomach, but he was stabbing. So, um, when he got off of him, all you saw was like blood. And Matthew looked down to hold it, kind of. He didn’t look down. He just went to hold it. And that was when he looked down. And then he went to go and keep going. But his body just collapsed on the floor kind of after Alex was like, “Bro, you need to stop,” but he kept going. And that was when he face-planted onto the floor.”

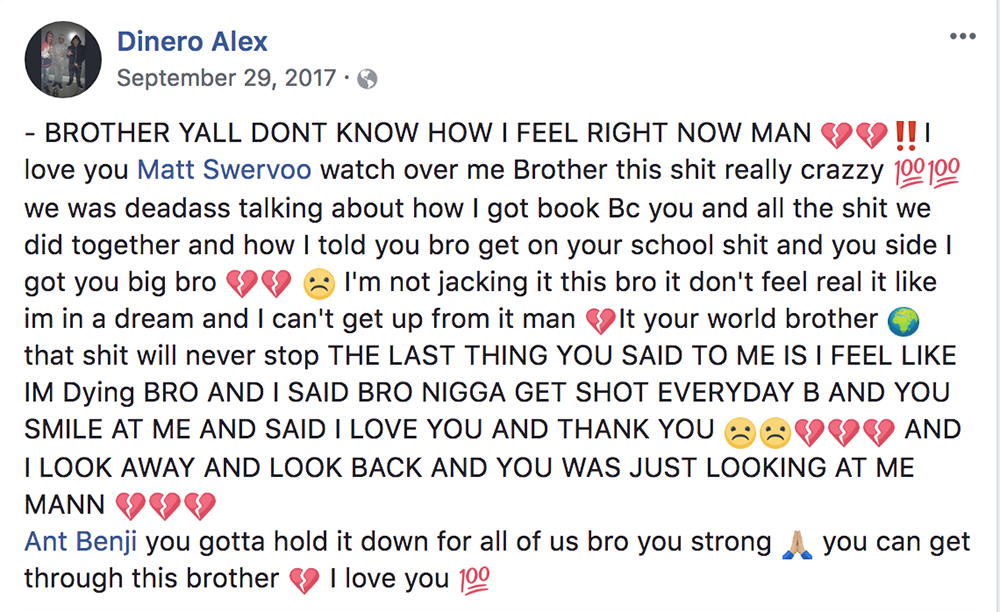

Two days later, on Facebook, McCree’s friend Alex, who was in the history classroom when the stabbing occurred, recounted McCree’s final moments and posted a memorial video for his friend.

https://www.facebook.com/alex.newpag.9/videos/vb.100014451614253/274194886405563/?type=2&video_source=user_video_tab

No Red Flags

Asked after the stabbing whether she had seen any “red flags” at UA Wildlife, then-Schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña said during an interview with a local cable TV news station, “I don’t think that that was something that was really apparent.” The scary thing is that it wasn’t. In a district that serves more than a million students, the central office operates based on data, and aside from the student surveys, the data showed that things were fine — because Fariña’s policies were designed to pressure principals to get the suspension rates down. For new principals, like Latir Primus and Astrid Jacobo, the pressure became particularly acute.

The easiest way to get discipline numbers down is to not enforce discipline. And then, on the rare occasion you have no other choice, take discipline off the books. Students and teachers said administrators did just this, simply telling students to go home for a few days. One student estimated this happened no more than 40 times in a given year; teachers told me they only found out about this from their students.

A Freedom of Information Act request for school emails in Washington, D.C., revealed that high school principals there systematically hid suspensions from district administrators. But at UA Wildlife, a similar request would have turned up nothing. Martinez explained, “For anything that would go on, [Jacobo] would always have us use the Gmail, the Google drive for everything. I remember once I emailed her directly. She said, ‘Thank you for your email. We have a Google drive for that.’ I didn’t understand it at the time.” Now Martinez, Vasquez, and others believe she did this to eliminate electronic evidence.

A few weeks after McCree’s death, the records of Matthew McCree and Abel Cedeno were locked on Skedula. Shortly thereafter, Skedula was overhauled. Years of data were deleted, and the new version at UA Wildlife stores data for only 14 days. Said Charles, the STEM teacher, “the section we had to report incidents was blocked.” After that, said Newman, the current humanities teacher, “verbally we were told [by administrators] not to put anything on Skedula that related to behavior. Everything had to be on paper.” Commented Garcia, the former STEM teacher, “So I’m going to fill it out, give it to you, you take it, throw it in the garbage, and call it a day? That’s just incorrigible. I don’t know how you can get away with shit like this.”

This shift in software and standard practice was not confined to Urban Assembly Wildlife. The New York Post wrote that the dean of Junior High School 80 in the Bronx “warned faculty about posting reports of student misconduct and disturbances on Skedula.” The reason? Because if the city Education Department reads those reports, “the higher-ups will ‘come after’ the school’s management, and question teachers’ performance, with reason to say ‘gotcha,’ ” the dean warned, according to the Post. If teachers can’t access records of student behavior, Vasquez noted, then, “Who knows how many reports like the one about Abel bringing a knife just aren’t in the system anymore?”

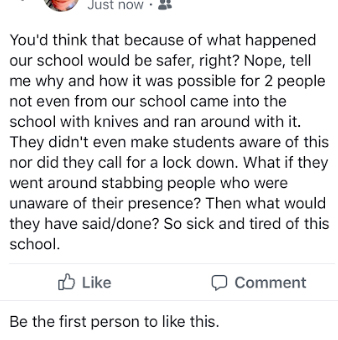

McCree’s death brought no accountability and no change. Principal Astrid Jacobo was not fired but rather was reassigned to a Bronx field support office to assist other school administrators. The city decided to close UA Wildlife at the end of this school year, but it became no safer after the incident. In January, Molly spoke out on social media about an incident that month:

The Urban Assembly nonprofit, which helped to found a series of 21 small middle and high schools and currently provides them with support services, sent out an email saying it was providing extra counseling to grieving students. But students didn’t feel supported. McCree’s death threw the school into turmoil, and students who spoke out about the incident felt singled out by school administrators, then forced out. (Spokespeople for the nonprofit and for the city Department of Education declined to comment.)

“They’re really trying to convince students, or their parents, to make the students transfer,” a former student and friend of McCree’s named Maritza Vargas explained. “A lot of the ones who spoke up aren’t there anymore.” Vargas said she sensed a clear threat behind the counseling, saying it felt “like they were saying I wouldn’t graduate in Wildlife.” She transferred to another school. “Although I’m not in Wildlife anymore, I’m still devastated and it still affects me to this day to the point where there are days where I wanna give up in school but I can’t and I don’t allow myself to,” she said. “I want to do it for myself and Matt.”

Not Just These Kids, This School, This City, or This State

“Don’t look at these kids like they’re innately bad kids,” said Vasquez. “Kids test the rules. Where there aren’t rules, anything goes. And we weren’t allowed to have rules.” Vasquez and his colleagues said this isn’t unique. “The point is,” said Newman, “this isn’t solely at this school. I think this is a citywide thing.” Hernandez added, “It’s not only the city. It’s the state. If you suspend these kids, you’re out of compliance with the state.”

But it’s not just New York City or New York state. The Obama administration’s 2014 “Dear Colleague” letter on suspensions, motivated by federal Department of Education data showing that black students were much more likely to be suspended and expelled than white students, applied the pressure experienced by UA Wildlife on schools across America: Get your discipline numbers down, or else. This created incentives to produce ever-lower suspension numbers, to prioritize statistics over student safety.

Teachers are afraid to talk about this. Sidney explained, “People are not going to speak out, period, because it’s going to cost them their job.” It is, indeed, astonishing that after seeing a student stabbed to death, only two teachers agreed to be identified by name. But in cities where teachers unions give their members a voice on discipline in anonymous surveys, like Buffalo, New York; Oklahoma City; and Fresno, California, the comments sound like they’re coming from UA Wildlife faculty: administrators shutting their door to disorder, turning a blind eye to violence, systematically suppressing disciplinary records, even willfully excusing death threats.

Make Schools Safe Again

So, what is the best way forward? The city Education Department declined to comment on this story, noting that the investigation is ongoing. But when asked on local news a month after McCree’s death what could help avoid future tragedies like the one at UA Wildlife, Fariña noted, “One of the things in that particular school, they have restorative justice practice there. … For me right now, the training that we have to do citywide is the restorative justice. You know, our suspensions are down, our incident reports across the city are way down.”

Teachers at Urban Assembly Wildlife do not agree. Suspensions and incident reports were way down because administrators forced them down by hook and by crook, they say; administrators responded to the pressure to not discipline by not disciplining. UA Wildlife teachers believe that traditional discipline must be restored. “I think if the rules were enforced,” said Smith, “it would have never gotten around to this point.” But teachers were not allowed to enforce the rules.

Disrespect, bullying, threats, and even physical fighting were allowed to occur without consequence. A school where homophobia “wasn’t a thing” became characterized by constant homophobic bullying. UA Wildlife became a place where disrespect, fear, and violence were matters of routine, which went unaddressed, teachers say, because administrators wanted to make it look like everything was all right. The only thing different the morning of Sept. 27 was the knife.

It wasn’t what policymakers intended. But, teachers say, that’s what can happen when students understand that they can act badly with impunity.

“I believe that if our students don’t understand that there are consequences in life, there are going to be consequences for that,” said Smith. “The consequence for that is they’re going to be in jail or in the morgue.”

To share your stories, email meden@manhattan-institute.org.

Max Eden is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, specializing in education policy. This article was updated on June 13 with details of Eden’s previous research on, and analysis of, the issue of school discipline reform. Some additional Eden links you may want to read:

—The student discipline delusion (New York Daily News)

—School Discipline Reform and Disorder: Evidence from New York City Public Schools, 2012-16 (Manhattan Institute)

—Testimony by Max Eden before the House Judiciary Committee on School Violence (House of Representatives)

—Suspension Bans Hurt Kids (Manhattan Institute)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)