The State of LGBTQ Curriculum: Tide Is Turning as Some States Opt for Inclusion, Others Lift Outright Restrictions

Update, June 13: Erik Adamian’s title changed from “education and outreach manager” at the ONE Archives Foundation to “associate director of education” before the original publish date of this story.

Bayard Rustin was a lead organizer of the March on Washington in 1963, a close confidante of Martin Luther King Jr. and a fiery voice for desegregation. In most U.S. history classes, that might be all students are asked to learn about him. But Rustin was also openly gay, and he became a prominent gay rights advocate. That fact in particular might now receive new attention in public school classrooms in Colorado and New Jersey.

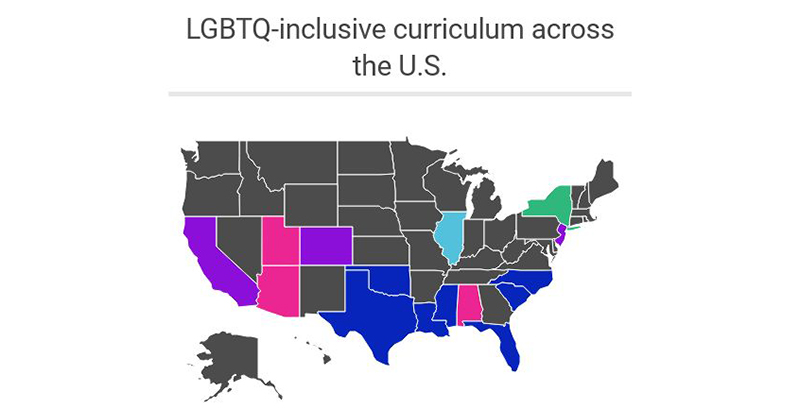

Those two states are the first to follow in California’s footsteps by mandating recognition of the contributions of LGBTQ people in history and social studies curricula earlier this spring. The legislation — combined with similar measures under consideration in New York and Illinois and votes to lift curricular restrictions on LGBTQ content in Alabama and Arizona — marks a flurry of state policy changes on the subject this year.

Nationally, most states don’t have explicit rules around if and how teachers discuss gender and sexuality in the classroom. But the impact of LGBTQ-inclusive course content can be powerful, advocates say. The Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network, a national LGBTQ education organization, has found that schools with inclusive curricula were more likely to report feelings of acceptance toward LGBTQ students and have lower rates of student absenteeism linked to feeling unsafe.

So far, however, LGBTQ representation in curriculum has been slow to take hold. Although only eight states have some kind of legislation restricting LGBTQ content in the classroom, including Texas and Florida, a 2015 GLSEN study found that only about a quarter of teachers incorporate LGBTQ topics into their lessons.

In states without clear guidelines, teachers often report feeling unsure about how to make their curriculum more representative, says Mara Sapon-Shevin, professor of inclusive curriculum at Syracuse University. They’re also concerned about pushback from parents.

“Most teachers want to do it right and want to do it well but feel underprepared and not well resourced,” she says.

A growing number of national organizations have been working to help equip teachers with the tools to tackle potentially controversial topics, including LGBTQ history. ONE Archives Foundation is the oldest active LGBTQ organization in the country and has long worked to build public awareness of queer history. Recognizing the growing demand for LGBTQ content, the organization has begun collaborating with the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Los Angeles LGBT Center to produce tailored history lessons on feminist writer Audre Lorde, slain San Francisco official Harvey Milk and other LGBTQ figures and groups.

The other obstacle teachers can face is fear over parental objection — especially in states that haven’t passed inclusivity statutes.

“I talk to teachers a lot about these issues, and they’ve very engaged … but also scared about getting in trouble,” Sapon-Shevin says.

ONE Archives is based in Los Angeles, and it focuses mostly on California, which passed the FAIR Education Act, ensuring LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum, in 2011. But the organization has begun to work with teachers across the country and recognizes how complicated introducing LGBTQ content can be in a state without protections for it, says Erik Adamian, associate director of education for the ONE Archives Foundation.

“The only reason why backlash can’t and does not go any further than a bunch of protests [here] … is because we have the FAIR Education Act,” says Adamian.

“Sometimes the best thing we can say [to teachers] is ‘Hang in there.’ If there is an effort like the law in California, then we will be there,” he says.

For states with restrictions on LGBTQ content, the policies apply specifically to sex education and how teachers can describe safe practices to their students. The details of these measures run the gamut, according to Clifford Rosky, a law professor at the University of Utah.

In South Carolina, for example, state legislation prohibits health education teachers from engaging in any “discussion of alternate sexual lifestyles from heterosexual relationships.” But in North Carolina, teachers are told simply to explain “the benefits of heterosexual relationships.”

Although these policies only specifically cover sex education lessons, many teachers run into confusion over whether mentioning a historical figure’s gender identity or sexuality counts as sex education content, Rosky said.

“The design of the laws was to make broad ambiguous prohibitions so that the topic would be ignored altogether,” he said.

Since 2017, Utah, Arizona and Alabama have lifted LGBTQ curricular restrictions — a move Rosky says generally garners more bipartisan support than instituting inclusivity mandates. Legislation that bans discussions of LGBTQ people increasingly lacks broad support, even among conservative groups. The repeal votes in the Utah House and Senate were both nearly unanimous. The reasons more states haven’t removed these policies, says Rosky, have more to do with the cost, time and potential for outing LGBTQ children in lawsuits than ideological opposition.

On the other hand, conservative groups have strongly challenged mandates, arguing that references to gender and sexuality shouldn’t be forced in schools and are best reserved for family discussions. The Alliance Defending Freedom, a prominent conservative Christian organization, has fought against incorporating LGBTQ content into public school curriculum.

The ADF did not respond to multiple requests for comment, but a section of its website discussing “parents’ rights” reads, “Today, sexually explicit or homosexual materials are frequently mandated for children as young as kindergarten, many times against their parents’ will, and often in the name of ‘tolerance’ or ‘safe school lessons.’”

Republican officials have also expressed skepticism about mandating LGBTQ history lessons. After the Illinois House of Representatives approved an inclusivity mandate, state Rep. Tom Morrison told NPR, “Here’s what parents in my district said: ‘How or why is a historical figure’s sexuality or gender self-identification even relevant? Especially when we’re talking about kindergarten and elementary school history.’”

Ultimately, however, the call is rising for students of color, students with disabilities, immigrant students and those from other marginalized groups to learn with materials that reflect their experiences, says Sapon-Shevin. LGBTQ curriculum is just one part of that shift.

Rosky agrees, noting that throughout history anti-LGBTQ discrimination was justified by a desire to protect children.

“What we saw in the last several decades is an increasing recognition that actually discrimination against LGBT people doesn’t protect any children — what it does is harm children,” he says. “It harms LGBT children and the children of LGBT people.”

Noting the prominent anti-gay activist Anita Bryant’s 1970s “Save Our Children” campaign, Rosky said, “In some sense, the LGBT movement is saying, ‘No, no, no, save our children.’”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)