New Book on School Segregation to Spotlight Landmark Dissent from Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer

Updated Jan. 2 | Clarification: An earlier version of this story failed to note that Justice Breyer will not be contributing new material to the book. A Brookings spokesperson subsequently clarified that the institution is “publishing his [Supreme Court] decision with additional annotations and context from another legal scholar.” Both the Brookings press office and coauthor Thiru Vignarajah — a former law clerk of Breyer’s who will be writing the book’s introduction — declined to comment for the original story.

The Brookings Institution has announced that it will publish a book based on a magisterial dissent by Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer from a case on racially segregated classrooms decided a decade ago.

Against Segregation in America’s Schools, tentatively scheduled for publication in 2019, will re-release Breyer’s dissent with additional updates on trends in segregation from the years that followed. While a press release from Brookings lists Breyer as the author of the book, the only material provided by the judge will be his 2007 dissent, said Brookings media manager Carrie Engel.

Racial integration in American schools, both at the K-12 and postsecondary levels, has been one of the major focal points of Breyer’s judicial career. He has repeatedly pointed to the Supreme Court’s ruling against legal segregation in Brown v. Board of Education — and the subsequent confrontation between President Dwight Eisenhower and Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus over the integration of Little Rock Central High School — as a turning point for American democracy and the rule of law.

In an interview in 2004, Breyer described the previous year’s Grutter v. Bollinger case, during which he voted with the majority to uphold the use of race as an admissions criterion in public universities, as “the most important case” he had yet participated in as a member of the high court.

“If we cannot bring a degree of diversity into institutions across the United States, we will not have a country that will function as a democracy,” he said. “If people don’t feel that ‘it’s our country too,’ how is this Constitution supposed to work?”

The progress of integration has often been questioned in the six decades since Brown v. Board, and heated battles over school choice in just the past few years have brought new attention to the issue. Most recently, an investigation by the Associated Press argued that urban charter schools were warehousing minority children in all-black enclaves.

Pushback to the author’s conclusions followed quickly from charter school allies and others in the education reform community. At The 74, academic and charter advocate Robin Lake called its analysis “misleading” and “irresponsible,” while the activist group Democrats for Education Reform questioned its focus on urban charters instead of predominantly white district schools in wealthy suburbs.

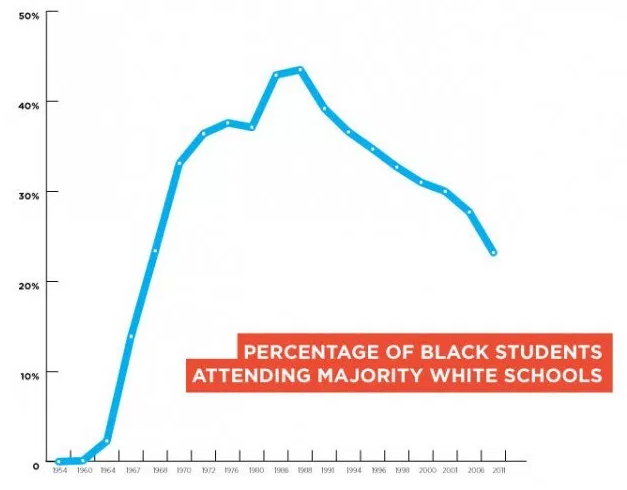

Regardless of their preferred remedy, however, figures within academia and the policy world are increasingly voicing concern over the problem of racial isolation. By the measure of black-white exposure — the percentage of black students attending majority-white schools — segregation is now as bad as it was in the late 1960s. Many observers have blamed the phenomenon on scaled-back oversight of public school districts by state and federal courts, which were the primary drivers of the integration movement of the 1950s and ’60s.

The Supreme Court, led by a conservative majority for most of the past 50 years, has been particularly reluctant to compel local authorities to initiate greater integration among students of different races and ethnicities. Justice Breyer, a liberal appointed by President Bill Clinton to the court in 1994, has previously (and unsuccessfully) argued against majority decisions that undermined local integration measures.

In 1995, in one of the first cases he heard as an Associate Justice, Breyer joined a dissent against a 5–4 majority in Missouri v. Jenkins, in which the court ruled that a local district court had overreached in compelling public schools in Kansas City to correct de facto school segregation through raising teacher salaries and creating magnet schools.

In a case that garnered much more attention, 2007’s Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District, Breyer again dissented from a 5–4 majority — this time penning a lacerating, 77-page opinion asserting that the court was betraying the legacy of Brown v. Board of Education. The court’s decision in that case, which declared desegregation plans in Seattle and Louisville unconstitutional because they expressly considered the race of district students as tiebreakers in public school placements, was a “radical” move away from precedent, he wrote.

In 20 minutes of impassioned remarks from the bench, the normally reserved judge struck an even starker tone, warning, “It is not often in the law that so few have so quickly changed so much.”

The lengthy written opinion will form the basis for the book to be published by Brookings Institution Press. Accompanying it will be updates on the status of school integration since 2007, during which time few would claim matters have improved. Large-scale examinations of attempted integration efforts in places like Ferguson, Missouri, have indicated that resistance among local parents to incoming black students from surrounding areas has not dissipated. Meanwhile, conservative scholars like the Heritage Foundation’s Salim Furth have argued that drawing the boundaries of school districts to cohere with segregated geographies of wealth and privilege will inherently lead to racial segregation.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)