Parkland Shooting Revives Calls to Roll Back Obama-Era Guidance on School Discipline, but the FBI Tells Lawmakers There’s ‘No Indication’ Issues Are Related

Correction appended March 21

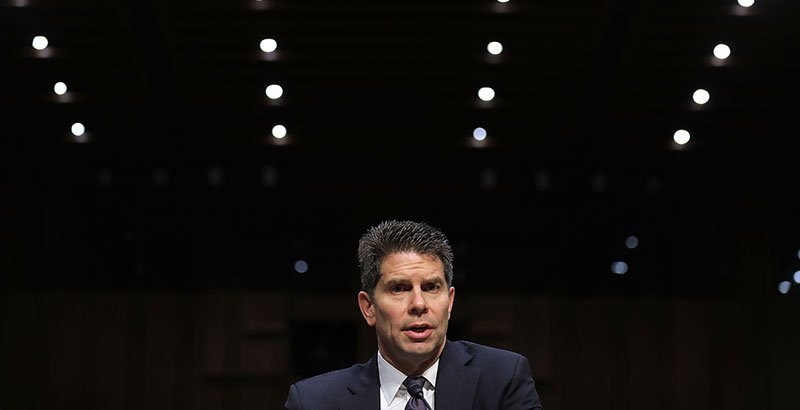

The FBI’s deputy director acknowledged Tuesday that the agency failed to act on several tips it received about Nikolas Cruz, who is charged with shooting and killing 17 people last month at a high school in Parkland, Florida. But he said an Obama-era guidance document on school discipline, designed to reduce racial disparities and the reliance on police for nonviolent offenses, played no role in its efforts to prevent such attacks.

“I don’t recall that guidance,” said David Bowdich during a House subcommittee hearing on law enforcement agencies’ response to the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, including tips the FBI and other law enforcement agencies received about Cruz before he opened fire on February 14. “We have no indication” investigators considered the guidance document when responding to tips about Cruz’s violent behavior, he said.

The congressional hearing follows claims by Republican lawmakers and pundits that the Obama-era guidance, issued in 2014 by the Departments of Education and Justice, has pushed local school districts to reduce student punishments or else face the wrath of federal investigators, effectively making schools less safe. Proponents, meanwhile, maintain the guidance is an important backstop to ensure that schools don’t discriminate when doling out punishments.

A heated debate over the guidance ensued long before the Parkland shooting, leading Education Department officials to meet last year with proponents and critics of that directive.

But the shooting has emboldened the document’s staunchest critics, who have called on Education Secretary Betsy DeVos to slash the guidance. Among lawmakers who have attacked the guidance since Parkland is Sen. Marco Rubio, Republican of Florida, who, in a letter to DeVos and Attorney General Jeff Sessions, said the directive “arguably made it easier for schools to not report students to law enforcement than deal with the potential consequences.” Last week, President Donald Trump said DeVos would head a school safety commission that would examine, among other items, a “repeal of the Obama Administration’s ‘Rethink School Discipline’ policies.”

Max Eden, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank, is among the 2014 document’s staunchest critics. During the Capitol Hill hearing on Tuesday, Eden argued that Cruz, who had a history of acting violently, should have been unable to pass a background check to purchase a firearm. The Broward County school district implemented a discipline policy in 2013 that aimed to reduce its reliance on suspensions. That local policy ultimately helped inform federal guidance, Eden said.

While acknowledging that the guidance doesn’t prevent officials from responding to violent offenses, Eden argued that the policy could have kept Broward County educators from flagging Cruz’s behavior over the course of several years.

“This policy of explicitly trying to push these numbers down can inhibit the good and fair judgment of school resource officers to issue arrests where they may be warranted,” Eden said, adding that arrests “feed into the system in a way that could have been constructive” in the Parkland incident.

But Kristen Harper, director for policy at the nonprofit Child Trends research center, noted that efforts to reduce racial disparities don’t contradict efforts to stop school violence. Racial disparities in school discipline are widespread among minor offenses, she said, but students across racial groups receive similar punishments for violent acts. Further, she said, the discipline guidance does not restrict schools or law enforcement from punishing students who are violent.

“In fact, there is explicit language in the guidance that says we should train school personnel to be able to distinguish between violent and nonviolent behaviors, and to determine when law enforcement needs to be brought in,” she said.

Rescinding the guidance, she said, could confuse school officials about their obligations under federal civil rights law, and would not result in improved student safety.

“The research does not support the conclusion that additional law enforcement presence [in] schools makes them safer,” she added. “We do know that increased law enforcement presence in schools increases criminalization of student behaviors.”

The discipline guidance also came up during a separate congressional hearing in Washington on Tuesday. Rep. Katherine Clark, Democrat of Massachusetts, asked DeVos about racial disparities in school discipline and the potential consequences arming teachers or increasing law enforcement presence in schools could have on students of color.

“I’m concerned about all students, students of color and all students,” DeVos replied. DeVos noted that the 2014 discipline guidance is under review, part of a Trump executive order to review all regulations within the Education Department.

“The stated goal of the guidance is one that we all embrace, to ensure that no child is discriminated against,” DeVos said. “We are committed to reviewing and considering this guidance and taking appropriate steps, if any are warranted.”

Carolyn Phenicie contributed reporting from Washington, D.C.

Correction: A Broward County judge on March 14 entered a not guilty plea on behalf of Nikolas Cruz, 19, who is accused of killing 17 people in the Feb. 14 Parkland, Florida school shooting. Court documents show that Cruz confessed to the killings but did not enter a plea after prosecutors said they would seek the death penalty, Information about his plea was incorrect in an earlier version of the story.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)