Teachers Urge DeVos Not to Scrap School Discipline Rules, as Civil Rights Commission Holds Hearing on Bias Against Disabled Students of Color

A month after educators and activists called on the Education Department to scrap Obama-era school discipline guidance that they say has sparked chaos in classrooms, an opposing group of teachers flew to Washington to fight back Friday.

In a meeting with officials at the department’s Office for Civil Rights, nine teachers argued that efforts to reduce suspensions have helped protect the civil rights of students, in particular children of color and those with disabilities who are more likely to be suspended or expelled than those who are white and don’t have special needs.

The meeting was scheduled after nearly 500 teachers emailed the administration demanding that their voices be heard, said Evan Stone, co-founder and co-CEO of Educators for Excellence, the teacher advocacy group that arranged the sit-down. Officials who attended included Candice Jackson, acting assistant secretary for civil rights; Jason Botel, acting assistant secretary for elementary and secondary education; and department attorney Hans Bader, an outspoken critic of the Obama-era guidance.

Friday’s meeting coincided with hearings at the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights on the root cause of racial disparities in school discipline, and whether schools comply with federal laws designed to protect children from discrimination. The discussions homed in on disabled students of color, who face disproportionate rates of suspension and expulsion, exclusion and restraint, and law enforcement referrals in schools.

The bipartisan commission is investigating federal civil rights enforcement under the Trump administration. The commission’s chair, Catherine Lhamon, authored the Obama-era guidance on disparate impact in school discipline that is now under fire.

“Schools have to avoid writing off children with disabilities and children of color as being born bad, and have to teach them and support them to meet the expectations that we have,” testified attorney Eve Hill, a former deputy assistant attorney general in the Justice Department’s civil rights division. “We have to eliminate the discrimination underlying that disproportion, reduce the unnecessary use of discipline and, for as long as those discriminatory attitudes exist, reduce the use of exclusionary discipline.”

Hill, one of four former Obama officials to testify, refuted accusations that the guidance encouraged districts to adopt racial quotas, an argument promoted by Bader. Lhamon said Trump administration officials declined to participate.

“I think it’s important to point out that the DOJ did not require schools to adopt discipline quotas or to get rid of any particular type of discipline,” she said. “Rather, the systemic remedies of root-cause analysis, data analysis, training, and policies and procedures were designed to change the discrimination that underlies the disparity.”

But commission member Peter Kirsanow, who was appointed by former president George W. Bush, shot back, pointing to recent policies at Minneapolis Public Schools as an example that districts are “adopting illegal quotas” and the government “doesn’t do anything to police” those policies. He also challenged the notion that schools engage in excessive discipline. Citing 2014 federal data, Kirsanow said 160,000 teachers were physically attacked by students, while 130,000 children were expelled — “so what’s the definition of excessive?”

One example, responded Anurima Bhargava, a Leadership in Government Fellow at the Open Society Foundations, is when schools punish students for their disabilities without providing them with adequate services. During the Obama administration, Bhargava served in the Justice Department as chief of the Educational Opportunities Section.

“Excessive is when you have students of color who are deemed to be emotionally disturbed and segregated out of classrooms at rates that are far beyond students not of color, and they’re placed in environments, in classrooms, in schools where they don’t get the kind of educational resources and they’re secluded from students who may be engaging in the same kind of behaviors but are not found to have an emotional disturbance,” she said.

A second set of witnesses at Friday’s hearing featured leading researchers from both sides of the school discipline debate, but the conversation quickly morphed into a back-and-forth between Daniel Losen, director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at UCLA’s Civil Rights Project, and Max Eden, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. Eden’s work, which has been cited by Education Department officials, argues that reforms to reduce suspensions have made schools more dangerous.

Central to the debate is a 2014 “Dear Colleague” letter from then-President Barack Obama’s Education and Justice departments, encouraging districts to examine their reliance on punitive disciplinary policies like suspensions and expulsions — and cautioned that those policies could constitute “unlawful discrimination” under federal civil rights law if they didn’t explicitly mention race but had “a disproportionate and unjustified effect on students of a particular race.” Lhamon maintains that the letter simply informed schools of their obligations under existing civil rights law.

The teachers who met with OCR officials on Friday maintain that the guidance document helped improve classroom climate and student behavior at their schools, moving their schools away from exclusionary discipline like suspensions and expulsions, and toward reforms like restorative justice.

“They shared stories about how they’ve looked at the data in their building and seen how bias has played out in their community,” Stone said. “They talked passionately about the hard work that needs to happen in order to shift that, and how important this federal guidance has been to spark those conversations, provide political cover for those conversations, and provide resources and supports for teachers to begin to move towards more restorative, relational discipline systems.”

In November, the same OCR officials met with the guidance letter’s biggest critics, who called on the Trump administration to reverse course. Among them was a former Minnesota teacher who suffered a brain injury after breaking up a fight in a high school lunchroom.

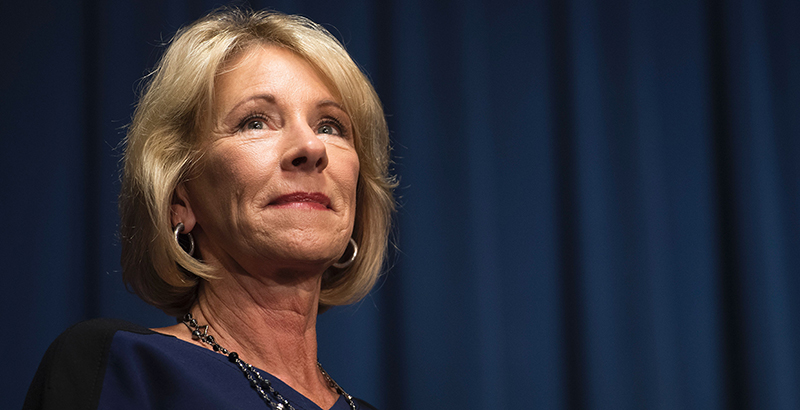

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has already moved to scrap similar Obama-era guidance documents, including a letter about the evidentiary standard schools should use to adjudicate campus sexual assault accusations. She also rescinded guidance that said schools must allow transgender students to use bathroom facilities that match their gender identity under Title IX, which protects students from sex-based discrimination in schools. Those policy shifts, and recent Education Department hiring decisions, have stoked rumors that the discipline guidance may be next.

For decades, researchers have documented widespread disparities in the way schools dole out exclusionary discipline to white and black students, though the driver of those disparities — and strategies to resolve them — remains highly contentious. The most recent Civil Rights Data Collection from the Education Department found that 2.8 million kids were suspended during the 2013–14 school year, and black students were 3.8 times as likely to receive an out-of-school suspension as their white peers. Additionally, the department found that students with disabilities were more than twice as likely to be suspended from K-12 classrooms as those without special needs.

The 2014 guidance contributed to a growing movement among educators nationwide who have replaced suspensions — particularly for minor infractions like tardiness or cell phone use — with alternatives like restorative justice. Researchers have found that students who are suspended or expelled are more likely to repeat a grade, drop out of school, or land in the juvenile justice system — a concept known as the school-to-prison pipeline.

Following discipline reform efforts at Los Angeles Unified School District, suspensions and expulsions have plummeted in recent years, though racial disparities persist. In 2014, state lawmakers approved rules that prevent schools from suspending kids for “willful defiance.” Misti Kemmer, a fourth-grade teacher in Los Angeles, told The 74 the Obama-era guidance document encouraged her school to improve. She was among the teachers who met with OCR officials Friday, and she encouraged them to keep the guidance in place because it’s helped improve the culture at Russell Elementary School, where she’s taught for 13 years.

“I can’t end poverty, I can’t end gangs in neighborhoods, but I can understand where kids are coming from, help them recognize what they’re feeling and how to deal with those things, because I can’t change what they go home to,” she said. “But I can help them function better, and if they can function better, then they can stay in school. If they can stay in school and learn, we can eliminate that school-to-prison pipeline.”

As the debate continues, DeVos’s and her department will be forced to pick a side. But after Friday’s meeting, Stone said there’s still time for teachers to make their case.

Department officials “said they have not begun formally reviewing this, that they’re under an executive mandate from the president to review all guidance that came out during the Obama administration, but they have not gotten to this one,” he said. “They have not started a process. They have not made a decision.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)