How States Try (and Sometimes Fail) to Combat Attendance Gaming and Errors as ESSA Ratchets Up the Stakes

What gets measured, gets done, as the popular education maxim goes. But what gets measured can also get gamed.

Tackling chronic absenteeism is now part of education plans under the Every Student Succeeds Act for 36 states and Washington, D.C., making student attendance a factor in determining school success under federal education law. The resulting requirements are also new, with many states crafting uniform definitions for chronic absence for the first time and reporting attendance data that distinguishes whether each student absence is excused, unexcused, or linked to disciplinary action.

The heightened accountability stakes for student attendance, paired with new types of attendance reporting, have some education experts worried that the data could be vulnerable to error or manipulation.

“Anything that has numbers can be gamed, and anything that has weight and influence can be gamed,” Phyllis Jordan, editorial director at FutureEd, told The 74. “But that doesn’t mean you don’t measure it.”

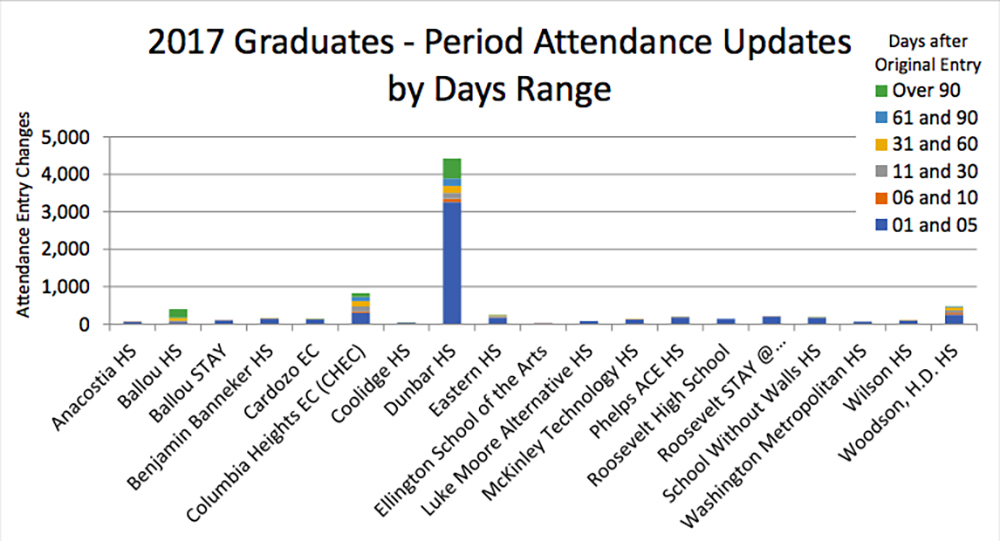

Such qualms aren’t completely unfounded. An audit of the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) released in January found that educators had manipulated attendance records for class of 2017 graduates. The most egregious was Dunbar High School, where records were tampered with more than 4,000 times.

In 2016-17, nearly 250 California schools reported perfect attendance, which education department officials have largely chalked up to data input errors.

Even in Connecticut, which was monitoring chronic absenteeism prior to ESSA, officials say they are facing surprising new obstacles as their system develops. They’ve become increasingly aware of schools dis-enrolling and re-enrolling students with extended leaves of absence, for example.

A crackdown on these kinds of errors is occurring as the accuracy of attendance data becomes increasingly integral to understanding chronic absenteeism and its negative effects on student success. Chronic absenteeism is linked to poor academic performance, delayed graduation, and higher dropout rates.

As states find their footing on the issue, they’re taking steps to ensure the most accurate data possible, education department officials in California, Connecticut, and D.C. told The 74. It’s a combination of vetting, embracing transparency, and developing detailed, easy-to-follow guidance.

“As you ratchet up the stakes, more and more people are paying attention,” Ajit Gopalakrishnan, the Connecticut department of education’s chief performance officer, said. “And ultimately, I think that’s a good thing. We want the data to be the best that it can be.”

Vetting the data

Officials from all three departments say they have data systems in place that help discourage manipulation and safeguard against errors.

In California, for example, schools and districts can’t submit their attendance data to the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS) — which the education department utilizes to monitor and aggregate student-level data for the public — without addressing all computer-generated red flags.

If a student’s absences and days attended don’t add up to the total number of days enrolled, an automatic error message pops up. If a pupil’s name is linked to more than one student attendance record, that’s another error. Any data point that’s left blank — error message. The list goes on.

Whenever there’s a new data collection, “you try to anticipate where you think there could be issues, and you put in [computer checks] to prevent that from happening,” Paula Mishima, the system’s education administrator, told The 74.

Following last year’s scandals, DCPS’s reporting system, Aspen, altered its attendance data submission windows to prevent changes after the 15th of every month. This could impede manipulations like the ones at Dunbar High School, where upwards of 1,000 attendance record changes transpired more than 15 days — sometimes more than three months — after the original attendance was submitted.

Connecticut’s data system, the Public School Information System (PSIS), is also designed to flag problematic submissions. The system generates an alert when a school’s year-to-year chronic absenteeism rate fluctuates by 5 percent or more. There are also flags for districts that report perfect attendance for individual students — the most common attendance anomaly the department observes, Gopalakrishnan said. He added that such warnings prompt a district to submit an explanation to PSIS about how it resolved the anomaly or confirmed the data.

About 5 percent of Connecticut students’ data this past year generated a warning because of perfect attendance, according to the department.

Another set of eyes

Sometimes, though, catching data anomalies comes down to a good set of eyes and diligent reviews of the data, according to state officials.

Connecticut staff who monitor PSIS, which also tracks where students are enrolled, have become increasingly aware of schools dis-enrolling and re-enrolling students who miss multiple weeks of school. In these cases, the department reaches out to districts directly — oftentimes finding that these districts, in the absence of concrete guidance, are unaware of when removing students is warranted.

There can be particularly ambiguous situations “where a parent says, ‘I’m taking my child and we’re going to Guatemala … and we’re going to be there for two months,'” Gopalakrishnan said. But “is that really a [justified] dis-enrollment from school” — where the child is receiving instruction elsewhere — “or is that an absence where that kid just isn’t getting any other education?”

The department now actively looks for these types of exits and re-entries, he added. When applicable, it explains to districts why their dis-enrollments are “inappropriate” and should be altered in the system.

“It’s not just an accountability game,” he said. “We want [districts] to [properly report] so ultimately kids have better educational outcomes.”

In California, data reviewers spotted the dubious anomaly of perfect attendance at hundreds of schools while sifting through reports from 2016-17 — the first time California collected attendance data under ESSA’s new requirements.

Many of the 246 schools that reported perfect attendance to CALPADS had transferred information from their student databases incorrectly, Mishima said. “We sent them letters and told them to tell us either that their data was wrong or that their data was right; and if it was wrong, what they were going to do to ensure it was of quality this coming year.”

Mishima couldn’t confirm how many of those schools had made an error, or whether such errors were found for the 2017-18 school year.

DCPS, meanwhile, is expanding its oversight via a monthly review of attendance data beginning this month, Amy Maisterra, interim deputy chancellor of innovation and systems improvement, told The 74. The district also released at least three public attendance data updates this spring — a show of transparency and accountability that Maisterra said should continue in some form during the 2018-19 school year.

“I know that the chancellor is very much in favor of the ongoing transparency that we put a big emphasis on this spring,” Maisterra said.

School officials and members of the public now can view attendance data at the district and school levels for every state and D.C., thanks to an interactive tool by the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project.

Staying on the same page

Analysis of 2015-16 federal chronic absenteeism data released earlier this year revealed an increase of about 800,000 students reported as chronically absent across the U.S since 2013-14. Experts partially attributed this increase not only to beefed-up data reporting systems, but also to growing educator and administrator awareness of their state’s attendance procedures.

Following last year’s scandal, DCPS released a new attendance policy guidance in June that details the district’s approach to defining and handling chronic absenteeism. It includes at least 18 examples of what can constitute an “excused absence,” steps for intervention, and “prohibited” school actions, such as prematurely dis-enrolling absent students.

The district also mandated “intensive” trainings related to attendance with all school leaders at its Annual Summer Leadership Institute in July.

“We found that a core piece of the work needs to be making sure people are clear with expectations, and that they have support,” Maisterra said.

California and Connecticut’s education departments also help coordinate trainings and provide detailed guidance for educators and administrators. In Connecticut’s case, the need for guidance prompted the creation of a workgroup, which includes Attendance Works, nine Connecticut districts, principals in Baltimore City Public Schools and Arkansas, and the Arkansas Campaign for Grade-Level Reading.

The goal of the group is to establish “culturally [sensitive] messaging to families” on the topic of extended absences, Charlene Russell-Tucker, the department’s chief operating officer, told The 74.

“We’re in the midst of doing that now with our districts … and also some districts in other parts of the country that have had some success around this,” she said.

Gopalakrishnan emphasized that these kinds of developments to improve attendance reporting are a “never-ending” process.

“Every time you feel like you’ve resolved a situation or given guidance, something new comes up,” he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)