Living and Learning Among Refugees in the ‘Ellis Island of the South’

For Atlanta-area students who have fled war and oppression, Allie Reeser does more than help them learn. She’s a translator, parent guide and neighbor

By Linda Jacobson | June 22, 2022This is one article in a series produced in partnership with the Aspen Institute’s Weave: The Social Fabric Project, spotlighting educators, mentors and local leaders who see community as the key to student success, especially during the turbulence of the pandemic. See all our profiles at ‘Weaving School Success’

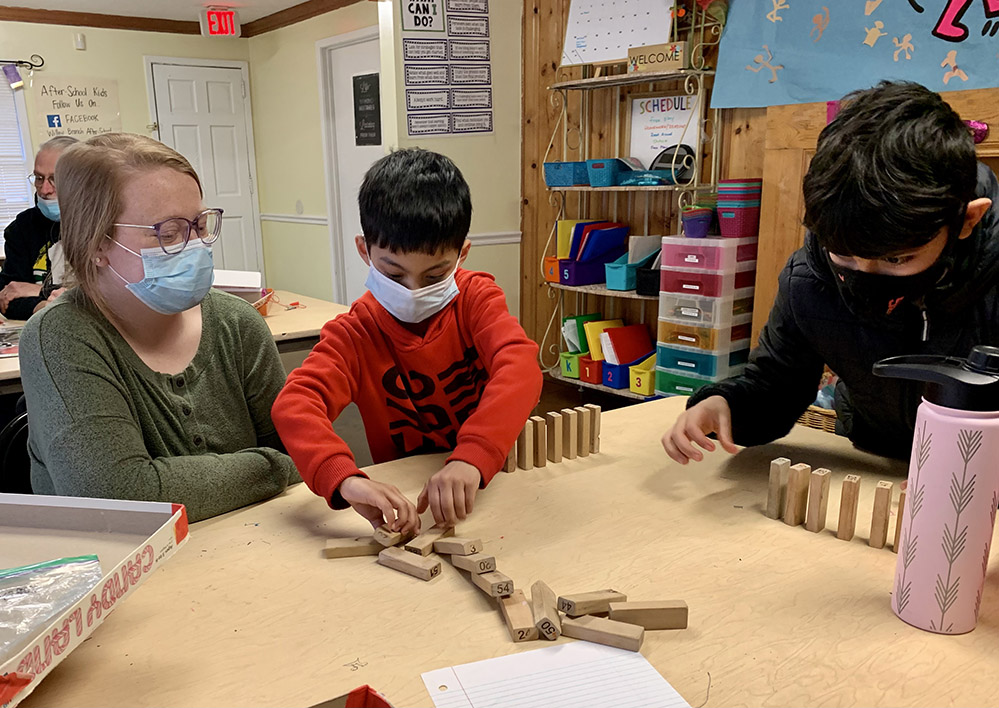

Holding her fingers up, Allie Reeser asks the dark-haired girl in a bright, sunflower top how many times 2 goes into 8. Hakima, a fourth-grader from Afghanistan, has a lot of catching up to do, like learning multiplication tables.

Pinpointing those skill gaps — and understanding the international backstories behind them — is Reeser’s job.

“If mom can’t read the homework, mom can’t help with the homework,” said Reeser, who leads an afterschool program at Willow Branch, an apartment community in Clarkston, Georgia that is often the first stop for refugees settling in metro Atlanta. As if making their way to the U.S. wasn’t hard enough, the pandemic’s two years of remote learning put students even further behind. “We have second- and third-graders who don’t know their ABCs.”

Reeser’s ability to weave these families into the community is often their key to success in school and beyond. And it all starts at home: Reeser, 29, has spent the past five years living among them at Willow Branch. Before the pandemic forced social distancing, her second-floor apartment served as a regular hangout for children late into the evening. To parents, she’s a guide, friend and neighbor, leading them through the bureaucratic thickets of their adopted country and offering assistance with everything from getting a driver’s license to communicating with doctors.

The program, which occupies the back of a leasing office, is part of Star-C, an Atlanta nonprofit that offers tutoring and enrichment to students in developments located near schools on the state’s low-performing list.

“She has been instrumental in building trust with families that don’t look like her,” said Margaret Stagmeier, Star-C’s founder.

Stagmeier, a real estate investor and landlord, began the nonprofit in 2014 with the philosophy that strong schools, affordable rent and access to health care help stabilize communities. Willow Branch, a 1970s-era colonial style development, is one of four Star-C properties in metro Atlanta.

Since the 1970s, when scores of Vietnamese families fled the country in the aftermath of the war with the U.S., Clarkston has become known as the South’s Ellis Island, and now takes in more refugees per capita than any other American city. Willow Branch’s tenants have fled war and oppression — in Burma, Sudan and, most recently, Afghanistan.

Star-C is not a religious organization, but for Reeser, the daughter of a minister whose nearby church supports Clarkston’s refugees, living with immigrant families and offering their children a welcoming place to learn is simply an extension of the values she grew up with.

That means helping high school students apply for college financial aid, sharing watermelon with residents outside on humid evenings and accompanying expectant mothers to the obstetrician — even though she doesn’t speak their languages.

She bridges that divide with hand signals and relies on older children to interpret the rest.

“I speak body language, and that’s an important one,” she said. “But I’m pretty good at picking up what’s going on.”

Tarri Johnson witnessed this firsthand during pre-pandemic health fairs that featured routine screenings for adults and immunizations for children.

“She would use gestures to help the patients understand even when we couldn’t,” said Johnson, a manager for Medcura Health, a chain of clinics that works with Willow Branch. “She just had a rapport with them.”

Reeser began volunteering as a tutor in the complex at 14. She went on to earn a degree in theology and children’s ministry at Lipscomb University in Nashville and considered a career in teaching. After graduation, she returned home just as the Star-C position became available.

‘Mission work’

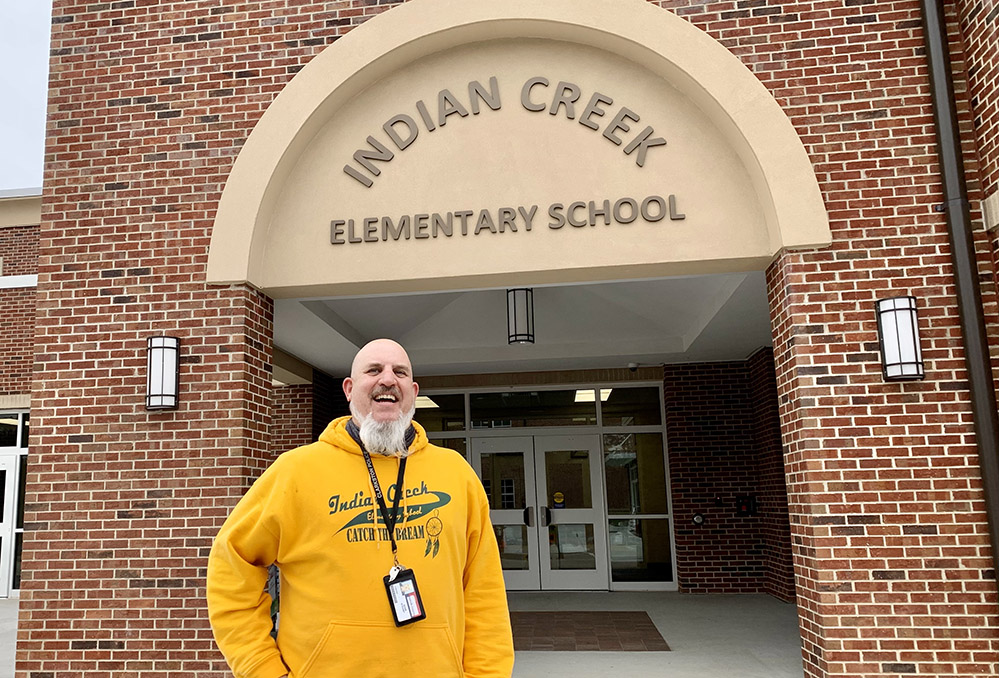

At Indian Creek Elementary School, which backs up to the iron fence surrounding the apartments, staff depend on the bond Reeser has with the families. She helps parents make sense of jargon-laden school memos and escorts them to events to meet their children’s teachers.

“Parents don’t know how to introduce themselves,” said Adam Nykamp, who has worked at the school for 22 years and oversees its STEAM program. Having Reeser on hand makes an American tradition like back-to-school night less intimidating.

A new student arrives almost daily at Indian Creek, where 80 percent are English learners, representing 40 languages. That alone is a challenge for any school. When Stagmeier bought Willow Branch, Indian Creek was a failing school, unable to hit annual achievement targets. Now it’s rated a B in the state’s accountability system, which gives schools credit for showing growth.

Reeser had a small hand in that turnaround. She stocks the center’s shelves with donated games, books and puzzles. She reviews material with students before state tests. But she thinks the children benefit the most from their regular interaction with staff and volunteers.

“They’re getting so much English help right now,” Reeser said on a sunny Monday afternoon in January as she watched the children play outside with 16 college-age volunteers from South Carolina. The visitors from OneLife Institute, a nonprofit gap-year organization for college-age youth interested in ministry, were spending a week in Clarkston to learn about the resettlement process. One group played tug-of-war while other children asked for piggyback rides.

Barbara Porter, a retired educator, used to tutor children every Tuesday afternoon. She called Reeser’s life at Willow Branch “mission work.”

“You don’t just go in and take over for a couple weeks and leave,” she said, adding that she can’t bring herself to erase the reminder of the weekly shift. “I still have it on my phone. I don’t want to take it off because I’d like to get back in.”

The afterschool program is also a training ground for first-year medical students at Emory University. They developed a nutrition curriculum with Reeser and turned the center’s back study room into a library.

The partnership “gives us good insight into the community that we’re going to be working with,” said Cassidy Golden, a medical student interested in pediatrics and underserved communities. “Allie is such a pillar of consistency in these kids’ lives. She’s there every single day.”

‘Sense of identity’

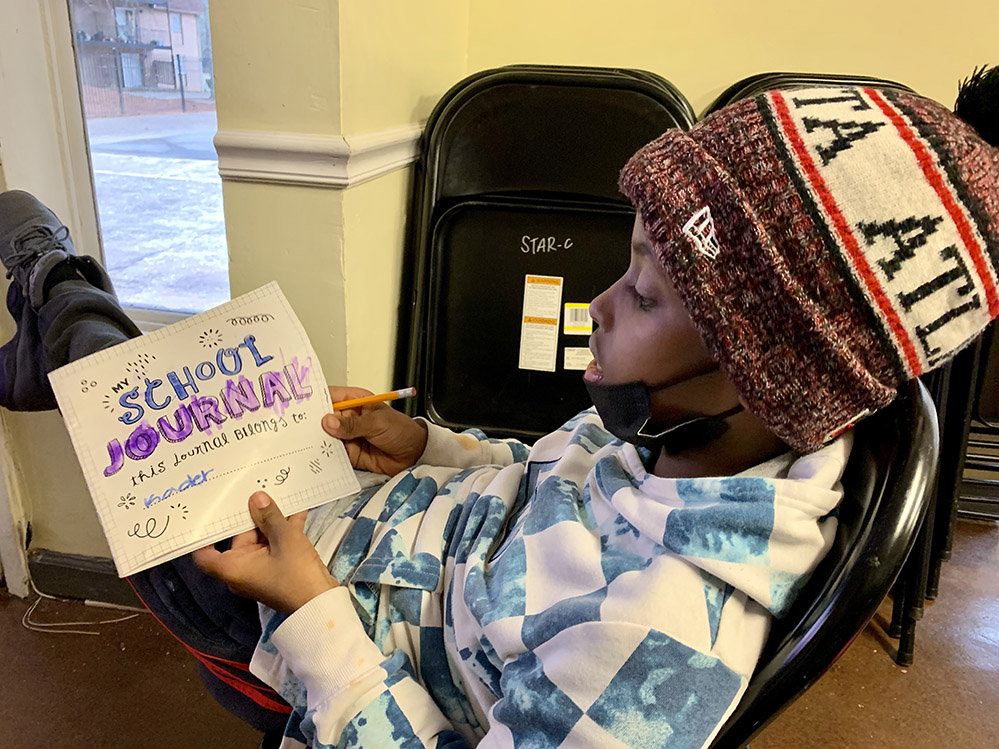

So are many of the children. Ten-year-old Kader Mohamedzen — whose mother is from Ethiopia and father from Eritrea — has been a regular since he was in pre-K. On a Friday afternoon in January, he kept glancing up at a Christmas movie on TV while practicing his opinion writing in a journal. Attendance at the program is light on Fridays because many boys accompany their fathers to prayers at the mosque across the street.

“Allie is a really good person,” Kader said. “Before corona, she took us on field trips. She took us to the dentist and a soccer game.”

She also cooked for Kader and his sister Flower when their mother was in the hospital with pneumonia a few years ago, said their older brother, Ogbai Afeworkie, a student at Georgia State University.

Afeworkie’s father was among those displaced by the conflict between Eritrea and Ethiopia in the 1990s. His father and mother lived in a refugee camp for eight years before arriving in the U.S. in 2005.

“They had to apply and do a lot of interviews and, most importantly, be patient,” said Afeworkie. Now his parents work as housekeepers, often picking up overtime hours because their children are in the afterschool program. Reeser, he said, has helped his family acclimate to the U.S.

“She explains the bills. She explains what the teachers are asking and what [my mom] is signing,” Afeworkie said. “My mom would say that Allie is like a gift from God because she has helped us so much.”

Many families stay in touch with her after they’ve left the program. But as they gain enough financial security to buy houses of their own, they sometimes lose the support they enjoyed at Willow Branch. Their children, Reeser said, might have a harder time making friends.

“My kids want to go back. It helped me a lot,” said Nshirimana Gorette, a Burundian mother of 11 who lived in the complex until 2020. Seven of her children attended the program.

The family was among the more than 300,000 refugees who fled political strife and human rights violations in Burundi, beginning in 2015. They spent time in a Tanzanian refugee camp.

Now living in a two-story, single family home on a cul-de-sac in Stone Mountain, about seven miles away, the family is no longer eligible for Reeser’s program. But that didn’t stop her from guiding Karohe Dunant, Gorette’s oldest son, through the college application process.

“She was a big supporter in that phase in my life,” said Dunant, now at tuition-free Berea College, near Lexington, Kentucky. Arriving in the U.S. as a young refugee, he fought feelings of inadequacy. “She instilled in me self-esteem.”

Reeser keeps in contact with older children through social media. She’s sympathetic to the pressures on adolescents, pulled between family traditions and the relative freedom of Western culture.

“A lot of these kids don’t really relate to their parents, and they don’t really relate to Americans. Their sense of identity can be confusing,” she said from her apartment, where a woven “Welcome” banner made by a Nepalese mother hangs over the kitchen doorway.

Reeser has felt that turmoil in her own family. Her 19-year-old foster brother is an orphan from Myanmar who arrived in the U.S. about six years ago. Bullied in middle school, he got into fights and was sent to an alternative program, where he began using crack.

“She knows very well how difficult it can be for these kids,” said Ike Reeser, Allie’s father, a minister at Northlake Church of Christ, about eight minutes from Willow Branch. “He’s truly one of the hardest cases.”

When she was still living at home, Allie and her foster brother enjoyed watching movies and sharing chicken wings. She said she tries to be someone he can feel “safe and secure around.”

As one of Star-C’s first afterschool directors, Reeser has helped build the model that Stagmeier expects to spread to more sites next year. In January, Star-C tapped Reeser to oversee all three of the nonprofit’s afterschool programs.

That means she’ll be spending a little less time at Willow Branch.

But the apartment complex will remain Reeser’s home. She’ll still shop at the same independent grocery store where residents buy halal meat and Burmese snacks.

“It shows that we’re equals,” she said. “I’m not trying to do some great thing, just be a good neighbor.”

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to both the Weave Project and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter