With Up to 9 Grade Levels Per Class, Can Schools Handle the Fallout From COVID’s K-Shaped Recession?

In Texas, Austin's NYOS — Not Your Ordinary School — gives 'bookend students,' who are far ahead & way behind, freedom to work at their own pace. It's a model that could head off the pandemic’s classroom crisis

By Beth Hawkins | August 7, 2021

Not for one second did the pandemic slow the red-hot housing market in Austin, Texas. Indeed, as COVID-19 untethered white-collar workers from offices in Silicon Valley, San Francisco, New York and other places with stratospheric costs of living, the city’s population swelled.

In January 2021, the city experienced the largest net influx of residents of any major metropolitan area in the country, according to real estate brokerage Redfin.com, which reported that shoppers in other states conducted 45 percent of Austin home searches, up from 32.6 percent a year earlier.

Is this good news, or bad?

In terms of traditional indicators, it means the economy was thrumming along, coronavirus notwithstanding. In 2020, at least 35 companies relocated to Austin, creating a record 10,000 jobs. Austinites new and old were flush with cash: As of March 14, a year into the pandemic, consumer spending was up more than 31 percent over January 2020.

But not everywhere.

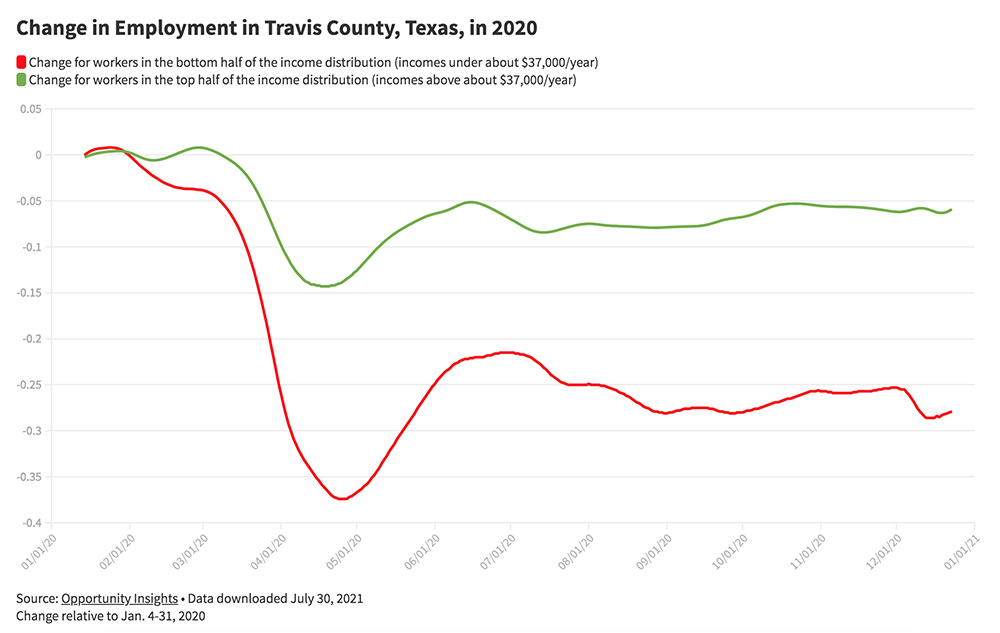

Because Austin’s new transplants were not spending their disposable income at the small businesses that are major employers of low-income workers, revenue was down 43 percent. Employment dropped 13 percent overall and 26 percent among the lowest earners, while rising 0.5 percent among those at the top.

At the same time, rents rose to the point where a minimum-wage earner would have to work a 125-hour week to afford a one-bedroom apartment; last year, the number of people sleeping on Austin’s streets increased 45 percent, the sort of crisis that puts homeless students even further behind academically than their low-income peers who have a roof over their heads.

Even Austinites with the wherewithal to buy a home found themselves priced out of the market. Outsiders’ house-shopping budgets were nearly 33 percent higher than locals’, averaging more than $850,000, versus less than $650,000. In some zip codes, housing prices are up as much as 46 percent, putting home ownership — a typical first down payment on intergenerational wealth and the security it affords — further out of reach. And, by extension, the possibility of moving into the neighborhoods with the most sought-after schools.

“Housing has become a luxury good,” Redfin CEO Glenn Kelman told the Wall Street Journal. “The economy seems to have officially split in two. There is so much hardship in one part, and then there’s just an absolute mad dash to buy houses in the other part.”

This is emblematic of what economists are calling the K-shaped recession. When the pandemic struck, economists John Friedman and Raj Chetty realized it looked different from previous downturns: While even small changes in the way money changes hands create ripples, COVID was a shockwave. The co-founders of Opportunity Insights — a team at Harvard University that researches income inequality and education’s potential to lift children out of poverty — persuaded credit card companies, payroll processors and other businesses that track money as it moves through the economy in real time to turn over what are essentially trade secrets. Using that information, the researchers built a nationwide online pandemic tracker capable of providing a down-to-the-day snapshot of who is spending and who is struggling, by income level, city, state and county and, in some instances, by zip code.

The data quickly revealed stunning implications on virtually every front.

Rather than a typical recession’s V shape, in which people across the socioeconomic spectrum experience both the downturn and the subsequent recovery together, the economists saw a K. Affluent Americans at the top of the K bounced back right away — much more quickly than in a typical recession. But their new spending patterns — buying fancy meal kits online rather than ordering in from neighborhood restaurants, giving up Uber rides and manicures — crippled the businesses that supported their lower-income neighbors; those impoverished families on the bottom continue to struggle disproportionately on every front, beset by challenges long proven to be detrimental to children’s ability to learn in school.

(Friedman and Chetty update the tracker as the underlying information changes. The data in this story was downloaded June 29, 2021.)

The Opportunity Insights tracker contains one academic dataset: student participation and progress on the math app Zearn, which one-fourth of the nation’s K-5 students have access to. Immediately after schools closed, use of the app among low-income students “completely dropped off,” notes Zearn CEO Shalinee Sharma. As they started logging on again, a yawning gap became apparent. A year into the pandemic, these students’ progress was behind where it should have been, while their wealthier peers were ahead 28 percent.

New studies by McKinsey & Co. and the nonprofit assessment concern NWEA found wide disparities between white/affluent students and their low-income peers/children of color. Depending on grade and subject, low-income students ended the 2020-21 school year with up to seven months of unfinished learning.

WATCH: Beth Hawkins details her latest investigation into COVID’s K-shaped recession and how the fallout will challenge America’s schools

Researchers, Friedman told The 74, fear the losses — of jobs, of loved ones to COVID, of mental health supports and reliable food supplies — may have even more devastating impacts for children that schools were already failing to serve, with education’s potential for lifting a family out of poverty moving further out of reach. In Austin, add to this list of barriers to classroom success an increase in homeless students and the exodus of families priced out of their homes, whose children tend to fall in the middle of their classes academically.

Even before the pandemic, a single classroom likely contained students who achieved at seven different grade levels — both behind and ahead. But because COVID has put the most disadvantaged students even further behind while hollowing out the middle, the span of academic mastery in individual classrooms is likely to be bigger. Pre-COVID, researchers at four universities used data from the 2016 NWEA MAP assessments, formerly known as the Measures of Academic Progress, to establish that in an average fifth-grade classroom, one-third of students perform at or below a third-grade level in math, a third at fourth grade, one-fourth at fifth and the remainder above grade level.

“The lockstep we’ve moved at for generations is just not going to work.” —Lars Esdal, Education Evolving

In June 2020, the researchers layered NWEA estimates of pandemic learning losses on top of that study to predict that the array of student needs in individual classrooms would widen further — spanning up to nine grade levels. The scholars predicted that post-pandemic, 24 percent of students in the average classroom would be on grade level and 33 percent each one and two grades behind, with small percentages of students one to four or more grades ahead.

Reaching students at varying levels of academic proficiency was already a major challenge for educators before the pandemic. In COVID’s wake, determining what skills each child might have missed during the crisis and figuring out how to fill the gaps presents a daunting challenge. A number of researchers have suggested that it’s time to consider shifting away from the traditional practice of moving students from grade to grade in age-based groupings, regardless of each pupil’s level of need.

“Given the data we’re seeing both about the level of variation that existed pre-pandemic and the level at which that variation is expected to increase, the lockstep we’ve moved at for generations is just not going to work,” says Lars Esdal, executive director of Education Evolving, a think tank that advocates for competency-based learning.

Five years ago, Austin’s NYOS Charter School — the acronym stands for “Not Your Ordinary School” — decided to confront the seeming impossibility of serving students who show up achieving at a wide array of grade levels. The school, which was founded 20 years ago by dissatisfied parents and admits children across the economic spectrum by lottery, had already gained a reputation for accommodating what Vice Principal Samantha Gladwell calls “bookend students.” These are both children who struggle in a conventional setting and those who learn very quickly. But school officials realized they would never be able to meet such divergent needs if they clung to the traditional calendar-based model.

The strategy NYOS’s educators chose — reconfiguring the way time and space are used so students can move through academic material at their own pace with classmates who are learning the same skills — worked better than they dared hope. In the 2018-19 school year, every grade in both reading and math students met or exceeded state averages, as well as scores in the Austin school district — sometimes dramatically.

NYOS earned an A on Texas’s 2018-19 state report card, while Austin Independent School District overall got a B. NYOS earned 96 of 100 possible points for student achievement and all 100 for closing achievement gaps. Neighboring district schools earned 88 points on both measures.

As a result, even before the pandemic struck, NYOS was looking to expand its model, known as competency-based education, and lengthen its school year. As it turns out, these are key strategies researchers are counseling as schools contemplate how to address yawning academic disparities when students return to class.

An ‘overwhelming’ job of catch-up

As real estate brokers and buyers alike are keenly aware, in most places, a neighborhood’s desirability is tightly tied to perceptions of its schools. Less known is that for the Austin Independent School District, it’s a two-way street: Administrators use real estate data — closings and construction starts — to determine, at the individual school level, where enrollment shifts are likely to take place. Coupled with demographic information, the data predicts steep ongoing enrollment losses even beyond the pandemic, continuing a trend the district has experienced over the last decade.

Since the 2012-13 academic year, the student population in Austin ISD has fallen from 86,500 to 75,000, as families have left for more affordable suburbs, as well as charter and private schools. The number of Black students fell from 6,266 in the 2016-17 school year to 4,975 in 2020-21. During the same period, Latino enrollment fell from 48,203 to 41,290. The low-income student population fell from 44,180 to 35,612.

The influx of new, wealthy Austinites isn’t likely to stanch the flow. In its most recent demographic report, Austin ISD noted that of the more than 41,000 new housing units slated for construction over the next five years, only some 6,000 are single-family homes. The district estimates enrollment of three or four pupils for every 10 single-family homes, but for every 10 condos and apartments — which make up the lion’s share of new construction — only one or two.

Financially, the district has held it together — so far. In 2019, Texas changed its school funding system, boosting per-pupil spending in the 2020-21 school year to an average of $12,000. That increase, plus federal stimulus funding and the state’s decision to continue to reimburse schools for students who never showed up, has shored up the bottom line for Austin schools. But with the district expected to lose some 5,600 more students by 2025, a fiscal cliff looms when pandemic relief funding runs out.

When Opportunity Insights analyzed student progress seven weeks after schools first shut down nationwide, students in wealthy communities had progressed in math by 37 percent, while impoverished ones had regressed more than 11 percent. As the first anniversary of the closures loomed, low-income students had made up ground, but their affluent peers were still ahead — by more than 30 percent.

In the 2020-21 school year, the number of Austin ISD students failing one or more courses more than doubled over the year before, from 3,300 to 7,600. On the 2021 state assessments, 60 percent of students scored at grade level in reading, down from 73 percent in 2019. Less than half — 48 percent — met math standards in 2021, compared with 74 percent the last time the exams were given.

NYOS has used a variety of assessments to get an early snapshot of students’ academic progress during the pandemic. In broad strokes, while its students are still faring better than their peers throughout the state, the number of early-grades students who were flagging in math and reading grew between fall 2020 and spring 2021. Older students were holding their own and in some cases making big learning gains.

In December, the education advocacy group Families Empowered surveyed 100,000 mostly low-income Texas families about their pandemic-schooling experience. Among Austin families canvassed, 56 percent said their children were not ready for the next grade. Four-fifths said their child needed support, with almost half calling the amount of catch-up “overwhelming.” The organization followed up with phone calls to a number of respondents to gather details. Asked what it would take to get their kids back on track, a third of parents said access to tutoring or other intensive support.

To ensure that schools can afford these more intensive services, Congress has mandated they spend at least 20 percent of their American Rescue Plan dollars on specific academic recovery efforts. But some experts say that doesn’t go far enough. Among other, more fundamental changes, some are asking whether it’s time to consider shifting to a model where students progress through academic material not according to their age or the school calendar, but their individual needs.

‘Diverse by demand’

NYOS enrolls a representative cross-section of the very different neighborhoods that stretch out on either side of Interstate 35, the unofficial moat that separates Austin’s affluent and historically white west side from its gentrifying east side. One-third of the 1,000 K-12 students are low-income, 40 percent are white, 36 percent are Latino and 14 percent Black. The school draws from a broad geographic area, so students go home to an array of housing and economic circumstances.

In contrast to integrated schools that describe themselves as “diverse by design,” NYOS leaders like to say their school is “diverse by demand.” It admits students by blind lottery but tends to attract applicants who want to learn at an accelerated pace, or are struggling to keep up, or don’t flourish in a conventional setting.

And there is demand. Over the summer, NYOS moved into a new, state-of-the-art building that will allow the school to begin drawing down its 3,000-student waitlist. It will add a few hundred pupils a year for a total enrollment of 2,000.

To judge by the architect’s rendering, NYOS’s new campus looks more like a WeWork than a traditional school. Sun-drenched atriums are furnished with tables of different sizes and shapes. There are chairs at long countertops and a broad staircase leading to a second floor that can be used as seating for an assembly. Halls are expansive, flanked by small, breakout-style workrooms and alcoves.

Students will start their days in classrooms with kids in the same grade, but from there will disperse into small, flexible groups with other pupils working on the same material. Because they advance as they demonstrate that they have acquired a skill or understand a concept, students progress academically as often as needed. They can advance at an accelerated pace in one subject while requiring extra support in another.

“The classroom won’t be the space where you spend your day,” says NYOS Elementary Principal Terry Berkenhoff. “It will be a place where you get situated.”

NYOS started the shift to what’s commonly referred to as competency-based education five years ago, as an outgrowth of the vision of the parents who founded the school in 1998 to keep student needs at the center of all decisions.

As the school became known for success with kids who had struggled elsewhere, its educators realized that small groups were better than standard, whole-class instruction for teaching large numbers of students with vastly differing academic achievement levels. Teachers already routinely assessed individual pupils’ proficiency to identify missing skills or concepts; using that data to enable students to move at their own pace was a natural extension. They could cover the precise material a handful of kids were ready for at the right moment — a strategy some believe can accelerate learning. And they would avoid the potentially damaging signal that gets sent when a student is pulled out of class for remediation.

Altering instruction turned out to be a much smaller challenge than changing the way adults’ time was organized. Teachers were accustomed to pacing material that’s supposed to be covered in a particular grade over a fixed number of days. Very quickly, kids started letting teachers know when they were ready for the next skill or concept. So the adults had to shift away from planning daily lessons to having materials prepared for students at a variety of levels.

“You have kids who are done with your week-long lesson plan yesterday and some who need a whole ‘nother week,” says Gladwell.

Teachers “loop,” staying with a group of students for several years. The familiarity this affords helps teachers understand each student’s needs.

The kids still take Texas’s mandated end-of-year STARR assessments, but it’s not a big deal. “The kids don’t worry about it, they don’t talk about it,” says Berkenhoff. “It’s just one experience in their whole learning career.”

In May 2020, Educators for Excellence surveyed 600 teachers and found strong support for grouping students by skill level and looping as strategies to help catch students up. Fifty-eight percent said they support small-group instruction, while 54 percent favored keeping students with the same teacher in the coming academic year.

Education Evolving’s Esdal says there are numerous reasons why schools should be considering the approach as they plan for what comes after COVID-19. For students at the bottom of the K, the economic crisis has caused problems that won’t be addressed by pouring on more conventional schooling, he notes. Children uprooted by homelessness or other disruptions don’t get any benefit from simply repeating a class.

A competency-based approach is “an absolute shift from using time as the constant and learning as the variable to learning as the constant,” says Esdal. “The biggest barrier is this involves changing the way we’ve always done things.

“We need to see this period as a pivot point,” he adds. “We have this system we’ve seen as ‘The Way’ for so long, and it just doesn’t work for many students.”

Rebooting for the fall

As progressive as NYOS’s approach is, competency-based learning will not be enough to make up for the pandemic’s academic losses, says Kathleen Zimmermann, the school’s executive director. Students will need more time in class, and many will need several years to recover. This is particularly true for those who already faced challenges and for very young pupils who have struggled in distance learning to acquire basic skills like reading.

Two years ago, the Texas Legislature passed a school finance reform bill that offered a carrot for lengthening the academic year. Under the new law, a school that offers 180 instructional days — the equivalent of 40 weeks — is eligible for an additional 30 half-days of funding. (Thirty states require 180-day school years, while 11 allow fewer. The average in Texas has been 173 days.) Pre-pandemic, NYOS had qualified for the money, which Zimmermann says may be used to start the next few school years early, or to run camps or intersessions during breaks.

This puts NYOS ahead of many schools around the country in addressing both the dizzying array of unmet student needs it will confront this fall and the special challenge of supporting children whose families have endured multiple impacts from the pandemic and the recession it sparked.

“We have to be really cognizant of what’s going on all over our community,” says Gladwell.

When COVID-19 hit, the school was about six months from the ultimate phase of transitioning to competency-based learning. Implementing both fluid student groupings and remote classes proved too difficult — at least, at first.

“In the crisis, we had to ask teachers to go back to doing one-size-fits-all,” says Gladwell. “To go back to everyone gets the same thing was just heart-crushing. We were so close to being able to keep it rolling.”

To rebooting its almost-complete competency-based model, add one more challenge NYOS teachers will confront in the fall: It is expecting upward of 300 new students, the first cohort to move off the waitlist.

It’s a good bet the newcomers will be unaccustomed to being accountable for themselves, say Berkenhoff and Gladwell. Accordingly, they are doubling down on teaching time management, critical thinking and self-regulation, among other things.

“We are going to have to be really on top of our processes for pinpointing what they need on day one,” says Gladwell. “It takes a ton of upfront work, but it’s so worth it when you see the child take ownership.”

This article is part of a series examining COVID’s K-shaped recession and what it means for America’s schools. Read the full series here.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Chan Zuckerberg Initiative provide financial support to Opportunity Insights and The 74.

Lead images: 1 and 4. Emmeline Zhao; 2 and 6. Getty Images

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter