An American Principal in Africa Is Using Lessons From the Ebola Epidemic to Confront COVID-19. U.S. Educators Can Learn From Him

By Beth Hawkins | May 17, 2020

Jeff Trudeau, director of an American school in West Africa, is riding out his second virus-related school closure. The first came in 2014, when his American International School of Monrovia was shuttered during the Ebola epidemic. He faced the same challenge then that U.S. education leaders now anticipate: having to accommodate returning students with wildly varying needs and abilities, and potentially too few teachers to help them.

The strategy Trudeau came up with — using diagnostic data to track what academic skills students were missing and using that information, rather than age, to group them — was more successful than he dared dream. At the end of the school year that preceded the Ebola closure, 74 percent of his students were reading at grade level and 66 percent passed math tests. The school year that followed was just five months long, but even after a prolonged closure, 82 percent of students passed the 2015 assessments in both subjects. In fact, his strategy was so successful that after the crisis passed, the school kept it in place, and it continues to use it.

As U.S. school leaders attempt to troubleshoot a very uncertain future, Trudeau suggests that they consider his lessons learned.

The story of the crises — plural — that birthed the plan is instructional.

COVID-19 came to Liberia much the way the Ebola virus did six years ago: slowly, at first, but then all of a sudden very quickly. With Ebola, there was a case in neighboring Guinea in February 2014, Trudeau recalls, and then a handful in March. By the time school let out in June, there was a case or two in Liberia.

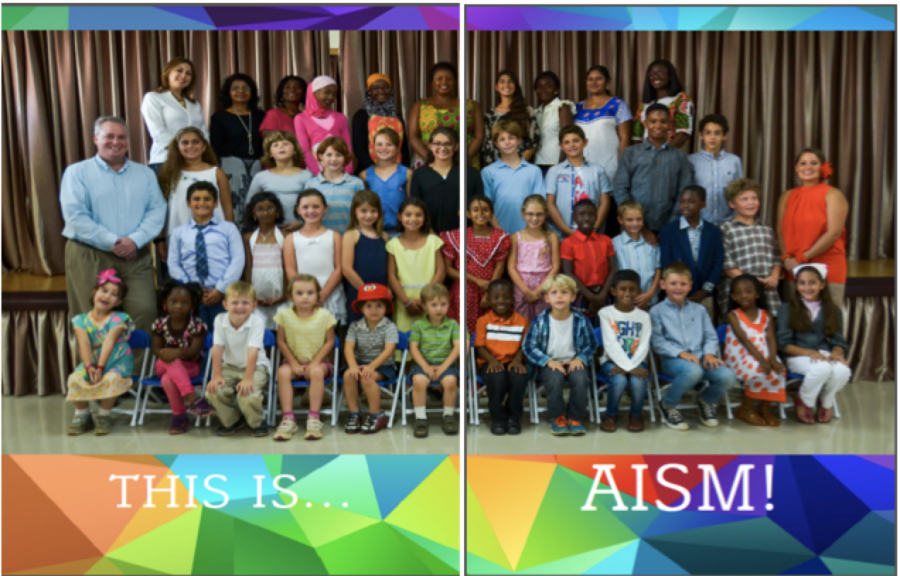

The American International School of Monrovia is one of 195 independent schools that have relationships with the U.S. State Department’s Office of Overseas Schools. It enrolls children from 18 countries, many of them dependents of diplomats or U.S. agency employees assigned overseas.

In the three months before the school year was supposed to begin in August 2014, the Ebola virus mushroomed into an epidemic that forced Liberia into lockdown. The families of most of the 150 students at the school were recalled to their home countries over safety concerns.

Ebola was still widespread when the school reopened in February 2015. Few of the recalled employees returned to Liberia, and those who did were reluctant to expose their kids to the classroom. Trudeau reopened with 38 students and just three teachers.

Sound familiar?

Red, white and blue

The physical aspects of reopening — social distancing for students, daily temperature checks, hand-washing and other school-day hygiene — were the easy part. The campus had been built to accommodate 600 students, but two civil wars had wiped out enrollment. So there was plenty of space.

Trudeau’s much bigger problems were figuring out which of the children returning had gained or lost ground during the six-month closure, how to equip too few teachers to make up for those losses and — as if that weren’t daunting enough — welcome some new students. Three days in, he administered the MAP, an assessment that can be used both to measure student growth and to identify weak or missing academic skills.

Of the 25 returning K-5 students, 10 had attended classes online during the closure through a contract with the for-profit charter school K12 Inc. and had lost ground on the U.S. academic standards the school uses. Those who had attended school in their home countries returned with an array of outcomes. The newcomers, too, were all over the map, depending on what learning experiences preceded their enrollment.

With only three teachers back at work, Trudeau assigned students to three groups — red, white and blue — based not on their ages but on the need revealed by the tests. Within those groups, teachers still needed to tailor instruction to each student, but the task was made easier by the similarity in strengths and deficits.

Ebola actually marked the second time Trudeau had tried using multi-age groups to address wildly differing student skill levels with too few teachers. In the early 2000s, he was the head of an international school in Venezuela when rising tensions between the United States and then-President Hugo Chávez resulted in the wholesale turnover of his school’s student body overnight. Instead of English-speaking children whose parents worked for U.S. oil companies, suddenly he had students from other countries who did not speak English.

The school couldn’t afford the 30 English as a Second Language teachers such a demographic shift would normally require. So Trudeau grouped kids by their proficiency in English. Students learned so quickly that the next year, he tried it in math.

“It’s not about their education, it’s about their previous learning experience,” he says. “If they weren’t used to a U.S. curriculum, if they weren’t used to speaking English, although some were.”

After the Ebola closure, his school’s students showed unusually strong growth despite the truncated school year. By May, no one was behind.

Schools often — and controversially — group students by ability. Typically, this involves setting the pace at which a group of students works faster or slower, or simplifying academic content.

Using the MAP allowed Trudeau to tap much more precise diagnostic data, which in turn enabled teachers to supply work that is more challenging and personalized. The test, which is designed not to measure grade-level performance but to identify strengths and weaknesses, is used to create a profile of each student’s understanding.

Every child gets an overall score in each specific subject as well as in what educators call instructional areas within those subjects. So a student profile in, say, math will yield information about skills such as algebraic reasoning, number sense, data analysis and understanding of probability.

The more precise the instruction, some believe, the faster the growth. And with students coming from many countries with different kinds of schools, it enabled Trudeau’s school to address each child’s prior experience, rather than performance expected at a particular biological age.

“The goal is not to track,” says Trudeau. “With this approach, we’re able to reach about 95 percent of our students.” In a small school, the strategy has also made up for the lack of full gifted-and-talented and special education departments.

‘The virtual has to be embedded in the school psyche’

The approach proved so popular with the families who trickled back after Ebola that the school kept it in place. Academic growth has accelerated over the past five years, with the school’s MAP scores on par with those of U.S. schools and outpacing results for other international schools in Africa.

“We still, in a one-grade homeroom, meet for 15 minutes every day,” he adds. “We have a morning meeting to work on social-emotional [learning], because you’ve got to feel safe and secure before you even focus on academics.”

After the meeting, students disperse to the first of their color-coded groups. When fresh data show that a student is ready to move ahead, Trudeau simply changes the child’s group.

This year, the school’s 125 students come from 18 countries. Three have parents who were working at the Chinese embassy before the shutdown, and 30 do at the U.S. embassy.

“The 30 students from the U.S. embassy most likely are in different English groups than the students from China,” says Trudeau. “But I’m sure if I went into the numbers, their prior learning experience in math might be higher, so they might be at a higher math group. And then the U.S. students who come from Arlington, Virginia, might be at a lower math group than their age-level Chinese peers.”

On March 17, COVID-19 forced the school’s second closure. This time, although students were repatriated to their home countries, the school was able to pivot to distance learning — again, the by-product of long experience of teaching in unusual circumstances.

Throughout the eight years Trudeau has been at the school, political upheaval has sometimes forced students to work remotely from their homes in Monrovia. So the school community has experience going back and forth relatively fluidly between in-person instruction and online classes. Today, the multi-age groups are working digitally, drawing on data from MAP assessments taken in early March.

Trudeau says a return to full-time brick-and-mortar school in August is far from certain. “It looks like there’s the potential that we’ll be throttling in, going live,” he says. “If that’s the case, we’ll wash hands with chlorine and we will do random temperature checks.”

But the school will likely stick with a version of what it’s currently doing, he adds: “We’d still have to have a robust online presence, because if there were to be a second wave or another outbreak, or if it were to become seasonal, the virtual has to be embedded in the school psyche.”

However the American International School of Monrovia starts the next year, it will be without Trudeau, who is moving to Burkina Faso. When he gets there, he hopes to introduce the concept of flexible groupings to his new school.

Lead photo: The American International School of Monrovia’s 125 students, now studying online because of COVID-19. (American International School of Monrovia)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter