With Former Top-Ranking Education Staff as Key Biden Advisers, Will White House and Ed Department Be on the ‘Same Page?’

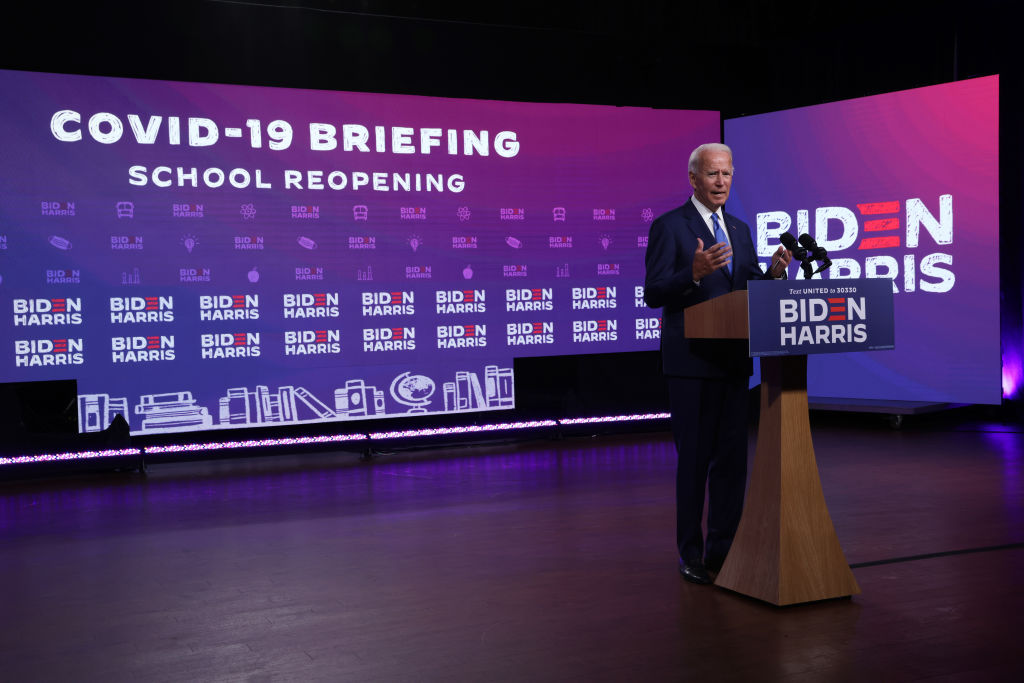

As President Joe Biden assembles a team of educators to lead the U.S. Department of Education, he’s also made key appointments to the White House that bolster his pledge to make education a major focus of his administration.

But the presence of Catherine Lhamon and Carmel Martin, who held high-level positions at the department during the Obama administration, at the top of Biden’s domestic policy team could raise questions over who’s in charge of his education agenda, according to those who have worked in past administrations.

For now, reopening schools is at the top of that agenda. And education secretary nominee Miguel Cardona, whose confirmation hearing is Wednesday, said on that issue, there shouldn’t be any confusion. Speaking last week on a radio program, he said it will be important “to make sure there is consistency in messaging, to make sure there is one message, one plan.”

Educators are eager to move past conflicting guidance from federal agencies on that issue as well as the Trump administration’s contentious focus on private school choice. While many are encouraged to have education experts in the West Wing — and former teachers at the top of the department — they also worry about the potential for mixed signals, particularly at a time of crisis.

“I think we are standing at a precipice in terms of rebuilding trust with parents and, to a lesser extent, teachers, on the issue of school reopening,” said Annette Campbell Anderson, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University who has been tracking state policies on school reopening.

During the Trump administration, there was a series of conflicting messages related to the pandemic, including whether the federal government would cover the cost of masks at schools. A government watchdog agency also found that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s safety guidance to schools was inconsistent.

Anderson added, “There needs to be someone who has Biden’s ear to help shape a comprehensive response.”

But the education department will have to carry out that response, said Noelle Ellerson Ng, associate executive director for advocacy and governance at AASA, the School Superintendents Association.

“Will we see tensions between offices at [the department]? Or between education staff at the White House and [the department]?” she asked. “I’d like to think not, and quite honestly, given all that has to happen around COVID, I think the path forward is pretty clear and narrow — an ‘all hands on deck’ scenario.”

The White House did not respond to a request for a comment.

‘The power center will be the White House’

There’s a precedent for White House staff taking the lead on education policy. And Margaret Spellings, who served as director of the Domestic Policy Council during George W. Bush’s first term before replacing Rod Paige as education secretary in 2005, thinks it will happen again.

Martin, Lhamon and Deputy Chief of Staff Bruce Reed, formerly president of the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, an education philanthropy, are already “in place and on the ground” and “know how to get things done,” Spellings said. “In the short run, the power center will be the White House,”

She should know.

From the White House, she oversaw the development of No Child Left Behind — a rewriting of education policy that fundamentally altered the relationship between the federal government and state and local education leaders.

“There was never a question in my mind” that Spellings was setting the priorities from the White House, said Susan Neuman, a New York University professor and literacy expert who served as assistant secretary for elementary and secondary education from 2001 to 2003. She added that Paige “was given a very clear sense that he was going to be the titular head, but not really in charge.”

Paige reportedly wanted to ease up on some of the law’s requirements that schools meet specific annual testing goals to avoid being labeled as failing, but found no sympathy from Spellings’s staff.

Neuman added that White House discouraged her and other political appointees from working closely with long-time civil servants at the department, which, she said, wiped “away the enormous amounts of expertise” of those who understood complicated funding rules and the nuances of federal education law.

Spellings said she might not have known much about Washington, but she knew Bush, having closely advised him while he was governor of Texas. She said she was “bullish” about building bipartisan support for NCLB, and thinks the same approach is needed when it comes to reopening schools. She said Cardona, as a K-12 educator, has the “ability to walk the walk,” but that both he and Cindy Marten, Biden’s pick for deputy education secretary, “have a lot to learn about Washington.”

Some found the relationship between Spellings and Paige to be unproductive.

“That led to a lot of dysfunction,” said Michael Petrilli, president of the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute, who helped create a new office at the department focused on education innovation and improvement during that first term. “Here’s hoping the Biden folks don’t repeat the same mistake, but it looks like they might.”

A ‘complementary relationship’

Under President Barack Obama’s administration, the balance shifted. With the Race to the Top program, then-Secretary of Education Arne Duncan drove an often-controversial agenda that pushed Common Core standards, charter schools, and using student test scores to evaluate teachers in exchange for federal grants.

As Obama’s education policy adviser, Roberto Rodriguez oversaw those initiatives at the White House. With experience in the Senate, leading policy work for then-education committee Chairman Edward Kennedy, Rodriguez provided a “calming influence” during what was “a highly charged emotional time,” said Deb Delisle, CEO and president of the Alliance for Excellent Education and the assistant secretary of elementary and secondary education from 2012 to 2015. Lawmakers had grown frustrated with NCLB and were lobbying for flexibility under the law.

“I found it to be a very complementary relationship,” Delisle said about working with Rodriguez. “That doesn’t mean we always agreed.”

During Obama’s second term, Rodriguez also took the lead on issues related to early-childhood education and higher education, which were not as much of a priority for Duncan.

Observers say Biden’s White House team and those he’s chosen to lead the education department have different strengths and ideally won’t get in each other’s way.

Both Martin and Lhamon bring considerable federal policy expertise and “have experience supporting the education secretary in previous roles,” said Khalilah Harris, the managing director for K-12 policy at the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank. She also served in the Obama administration.

Martin, who served as assistant education secretary for planning, evaluation and policy development, is now deputy director of the Domestic Policy Council for economic mobility. Lhamon, the former assistant secretary for civil rights in the department, is deputy director for racial justice and equity on the council.

“I anticipate them both serving as expert advisers and partners with Dr. Cardona,” Harris said, but added that as part of the White House, they now have “massive portfolios” that will require them to work across multiple agencies, not just education.

Martin and Lhamon, however, don’t have the classroom experience that Biden promised to bring to the department. Cardona and Marten have been elementary school teachers and principals.

“We’ll need to wait and see how this plays out. Personalities can make all of the difference,” Harris said, but added that “allowing Cardona and Marten to do their jobs will advance the Biden-Harris agenda more aggressively.”

A focus on fall 2021

Anderson, at Johns Hopkins, suggested that the task of getting most schools to reopen is so monumental that the messages to schools and families shouldn’t come from the White House or the department.

She has called for a blue ribbon commission on reopening that includes parents, students, teachers, administrators, public health officials and others “to chart a realistic path” to in-person learning.

“We ultimately need to focus our efforts less on the short-term agendas of individuals and try to focus on what a coordinated fall 2021 reopening could look like from a federal perspective,” she said. “There’s a lot to do between now and then even if everyone is on the same page.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)