For the Second Time In Less Than Two Years, Miguel Cardona is Set to Prove Himself on a Much Larger Stage. Is He Ready for the ‘Political Headwinds’ He’d Face as U.S. Education Secretary?

When Miguel Cardona began eyeing the Connecticut school commissioner’s job in 2019, Robert Villanova admits he was a “little bit skeptical.”

At the time, Cardona — now in line to be President-elect Joe Biden’s secretary of education — had been assistant chief in the small city of Meriden for four years. Villanova, director of the Executive Leadership Program at the University of Connecticut’s Neag School of Education and Cardona’s mentor, thought he might not want to leapfrog over being superintendent.

Cardona made the jump anyway. But it wasn’t without complications. The governor’s first choice for the job had been an experienced Black superintendent. Once appointed, Cardona had “a lot of heavy lifting to do to build up his credibility” in a state where he was a relative unknown, Villanova said.

Just over a year later, history may be repeating itself.

Biden’s team initially leaned towards a respected education scholar as its pick for education secretary, the Washington Post reported, and subsequent speculation focused on two union leaders. But in Cardona, he ultimately selected a relative cypher on the national scene, someone whose last job before leading the state for 16 months was helping to oversee a district of under 9,000 students.

Meriden is where Cardona grew up, and his hardscrabble upbringing helped inform a career aimed at helping the neediest students. Those who worked with him say his experience offers a unique counterpoint to the previous education secretary, a billionaire philanthropist and heavyweight fundraiser who consistently targeted what she saw as a stagnant public school system and the unions that enabled it. But some wonder whether Cardona has been tested enough to withstand the intense pressure he’ll face as leader of the nation’s schools at a time of unprecedented crisis.

“I just think it’s going to be a really steep learning curve for him,” said Dale Chu, a senior visiting fellow with the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute, who described the secretary-designate as a “blank slate.” “The levers to drive change are different, as are the political dynamics. Being a consensus-builder is all well and good, but it remains to be seen how he might leverage that to improve policy.”

What Cardona, 45, lacks in years of leadership, Villanova and others said he makes up for in his ability to work with teachers on often-contentious issues, from evaluation to lengthening the school day. During the vetting process for U.S. education secretary, Cardona “must have been able to tell a dozen stories about how he was able to connect conflicting points of view and come out with a better solution,” Villanova said.

Cardona, who the Biden transition team did not make available for an interview, first caught Gov. Ned Lamont’s attention by seeking out prominent state roles aimed at improving educational opportunities for students like him — English learners from low-income families who hailed from public housing. He led a legislative achievement gap task force and pushed for hiring more teachers of color. He also helped launch a new association of Latino principals and superintendents.

“He found himself in all the right places to be able to champion this work,” said Lauren Mancini-Averitt, president of the Meriden Federation of Teachers. As someone who was able to overcome poverty through a career in education, she added, “he felt compelled to bring other people with him.”

First elementary ed secretary

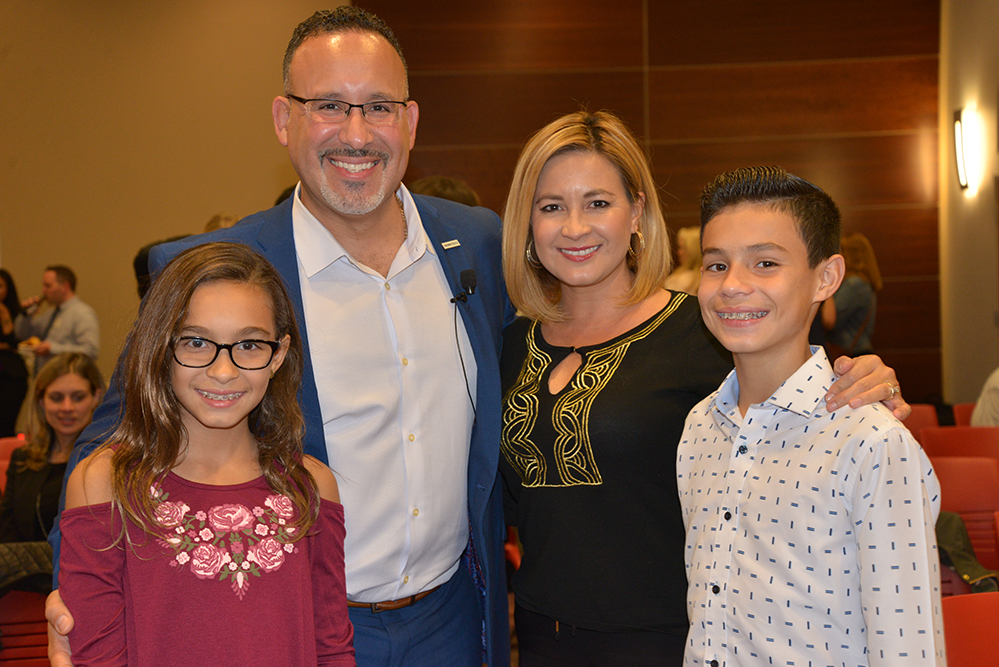

These views took root in Meriden, a faded manufacturing town divided by the Quinnipiac River, halfway between New Haven and Hartford. His children Celine and Miguel Jr. attend school there, and his wife Marissa, a former Miss Connecticut and singer, works in the district as a family-school liaison.

It’s also where he decided to teach and became a principal before he turned 30. If confirmed by the Senate, as appears likely, Cardona would become the first secretary in the department’s 42-year history with a background in elementary education.

He called Hanover Elementary School, where he served as principal, “Little Ellis Island” for its program serving newly arrived students needing bilingual services, his area of expertise.

At Hanover, he was a principal on the go. Mancini-Averitt said in her visits to the school, she didn’t know where Cardona’s office was “because he was never in it.” He spent time in classrooms, providing feedback to educators such as Mary Jean Giannetti, a science coach who worked at multiple schools. As soon as she left the classroom, she said she would receive an email from him with a “synopsis of what he saw and what he liked.”

School-based preschool programs, especially those that serve children with special needs, are often isolated from the rest of the elementary grades. But Katherine Lopez, who teaches first grade at Hanover, said Cardona emphasized inclusion and wanted young children with disabilities to participate in school assemblies, concerts and other events. He also pushed for teachers to participate in the same training opportunities as their K-5 peers.

“Hanover wasn’t just ‘housing’ the program — they were Hanover students,” she said. “He helped shift the view of special needs students in the building.”

Labor-management partnership

While serving as principal, Cardona also completed his graduate work. His dissertation focused on a subject close to home. The focus was a 9,000-student Connecticut district, where 43 percent of the students were Hispanic and more than half came from low-income homes. As is common in academic papers, the district was not identified, but in both size and demographics, it bears a striking resemblance to Meriden.

Cardona found that teachers assigned first and second grade books to English learners in the upper elementary grades instead of purchasing higher-level materials in Spanish that would allow them to learn grade-level content with their peers. District assessments didn’t give teachers enough information to gauge whether students lacked knowledge of the material or simply didn’t understand the language.

The district provided an ample proving ground for his idea that school leaders needed determination in the face of excuses — or as he called it, “political will” — to address achievement gaps among this population. But he worried about how his message would be received by educators he would continue to interact with.

“He said, ‘I’ve got to get this message out,’” said Barry Sheckley, a retired professor at the University of Connecticut who served as Cardona’s dissertation adviser. “He did a good job, tactfully and politically.”

A year later, in 2012, he was named a National Distinguished Principal. The honor attracted enough attention that district leaders recruited him for the central office position to shepherd a controversial state teacher evaluation system. The issue would put his theory about “political will” to the test. New state guidelines required that student test results play a bigger role in judging teacher performance — an issue dogging schools across the country.

That summer, Mancini-Averitt met with Cardona to ensure the new plan was acceptable to teachers and easier to follow. After cutting and pasting, and retyping didn’t work, Cardona grabbed some Post-it notes and started writing. By the end of the meeting, there were notes on walls, and all over pages of their original draft.

“He said, ’I think I’ve got this worked out,’” said Mancini-Averitt. While there was a lot of “give and take” and not everyone got what they wanted, she said, “the Post-it notes became an agreement.”

Not always popular

But he didn’t win over everyone.

Gwen Samuel, a resident who leads the Connecticut Parents Union, said on more than one occasion, she asked to talk to Cardona about bullying issues related to racial tensions among students. She was always given an appointment right away — more than parent advocates in other districts got, she acknowledged. But often, it never moved beyond talk.

“At least I got to meet with him,” she said. “His strength is that he listens to parents. That doesn’t always mean it would translate into action.”

Certainly, his reputation as a “bridge builder,” as Villanova calls him, got put to the test when he took the state commissioner’s job in 2019.

Like state chiefs across the country, he faced frazzled parents set on getting their children back to school and frightened teachers convinced leaders were putting them at risk. Last summer, Cardona initially asked districts to show how they would fully reopen in the fall, and said they would be out of compliance if they didn’t. While some parents favored the push, others bitterly opposed returning to in-person learning.

A Facebook group, CT Teachers Supporting a Safe Reopening Plan, continues to include Cardona among those they blame for a reckless response to the virus. Commenting on a recent article about educators who have died with COVID-19, the group posted that Cardona and others “demanding face-to-face learning have a hand in this.” The organization launched a petition against in-person schooling, arguing that reopening would reverse the gains the state had made in controlling outbreaks.

While he and Lamont backed off and let districts decide, Cardona continued to say students should be in school — a position that “has not always been popular with students, parents or teachers,” said Matthew Banas, a social studies teacher at Maloney High School in Meriden and a union leader. “But he has been steadfast in the face of criticism.”

Cardona also focused on eliminating the digital divide. A September study showed that 57,000 Connecticut households with children still lacked broadband access. The state used federal relief and private grant funds to ensure students could participate in virtual learning, and in December, Lamont announced that Connecticut became the first state in the country where all students had devices.

“He made great efforts in the areas of equity and access by getting computers and internet access to many students in need,” said Beth Reel, a co-executive director of the Connecticut Parent Advocacy Center.

Facing ‘political headwinds’

Obviously, the challenge of reopening schools will only expand if Cardona comes to Washington. Chu, the Fordham Institute fellow, suggested that while Cardona may have a “compelling personal story,” he’ll need to surround himself with “smart and trusted folks to help keep him honest” about those mostly interested in “access, influence and money.”

But others note that the previous secretary, Betsy DeVos had no school experience prior to helming the education department — one reason Biden promised union leaders his pick would be a teacher.

Marco Davis, president and CEO of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute, spoke with Cardona last week as part of a meeting for Latino leaders. A common criticism of past education secretaries has been that they were too far removed from the classroom. It will be hard to make that argument of Cardona, said Davis, who served in the Obama administration as deputy director of the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for Hispanics.

“It’s true he hasn’t been on the national stage,” he said, but in Cardona, Biden gets someone who “hasn’t been in any particular camp’s pocket” and “wasn’t so entrenched in one place.”

As the son and brother of a police officer, Cardona has said that for his family, “service was in our DNA.” But Sheckley, Cardona’s dissertation adviser, likes to remind people that there’s more to his protégé than a gripping biography. While Cardona went to a technical high school and attended state universities, he also draws from a strong research base focusing on how to improve educational opportunities for the least-advantaged students.

In Washington, Cardona would face “political headwinds” unlike anything he’s ever experienced, Sheckley acknowledged. But “when he gets crunched into a corner, he’s going to default to, ‘Do we or do we not have the political will to do what is right here?’”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)