Williams: Trump’s America Through the Fearful but Still Hopeful Eyes of My Old Brooklyn Student & Friends

In 2005, just as I was moving to New York to start teaching a classroom of Brooklyn first- graders, The Onion published an article, “ ‘Midwest’ Discovered Between East and West Coasts,” which traded equally in stereotypes of snobby coastal elites and homespun, sweatsuited “Midwestern Aborigines.” Back then, coastal alienation from the heartland was all fun and games. So many urban sophisticates were blind to the tenor of life of their fellow citizens in “flyover” states.

The 2016 election shattered this self-serving view of American politics. Fully two-thirds of white voters without a college education supported Donald Trump, a higher percentage than supported Mitt Romney in 2012 or John McCain in 2008. Now, the non-satirical media echo the Onion.

In the summer of 2016, The New Yorker published a deep dive from writer George Saunders with the headline “Who Are All These Trump Supporters?” Saunders found a “set of struggling people … pitted against other groups of struggling people by someone who has known little struggle … [who is] indulging the fearful, xenophobic, Other-averse parts of their psychology and reinforcing the notion that their sense of being left behind has no source in themselves.” NPR has converted “talking to a white Trump voter in the Rust Belt” into a veritable cottage industry. The New York Times has followed suit. Mark Lilla, writing in the Times 10 days after the election, called it “the media’s newfound, almost anthropological, interest in the angry white male.”

Perhaps this is appropriate. We live in a new political era powered by white males with limited post-secondary education and a variety of cultural and economic grievances. It’s important to explore the anger that drove Trump to the forefront of the Republican Party — and the country. While Trump’s overall approval rating dropped to 32 percent, the lowest ever in a Pew Research Poll released Dec. 7, his job ratings continue to be divided by race, gender, and education. While 40 percent of men approve of the way Trump is handling his job as president, only 25 percent of women do. Just 24 percent of adults with postgraduate degrees, and 27 percent of those with four-year college degrees approve of Trump’s job performance, compared with 35 percent of those who never attended college. While his approval rate among white Americans is 41 percent, it’s just 7 percent with African-Americans and 17 percent with Hispanics.

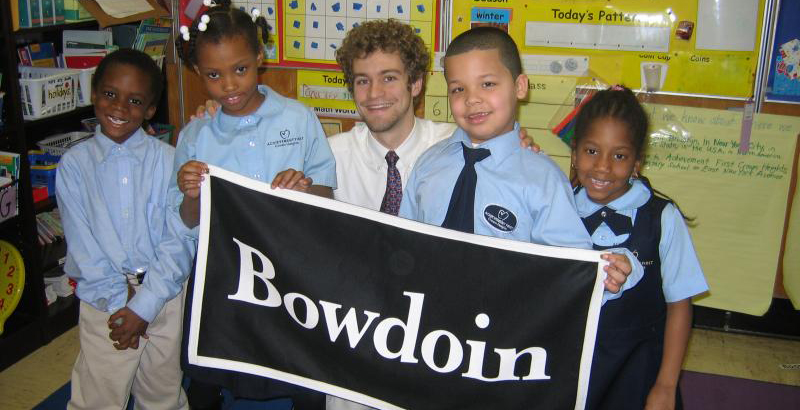

But white men’s fears are not the only fears. We should also wonder: What happens when a country indulges its older citizens’ deepest anxieties about the diverse younger generations growing into their places in the national community? What, I wondered, do my old Brooklyn students think of Trump? Some were graduating from high school this spring. So I reached out to the mother of one of my former students, and within weeks, I was chatting with him and four of his teammates from Achievement First Brooklyn High School’s highly successful speech and debate team.

None could vote in 2016. But as champion debaters, with a crowded shelf of trophies to prove it, they keep a close eye on the fraught national arguments over American ideals — and competing visions for the country’s future. They will likely live with the consequences of the country’s decision in November for much longer than most 2016 voters (two-thirds of whom were at least 40 years old on Election Day).

They are all children of immigrants, but that may be their only common identity. Esther Reyes, Esmeralda Reyes, and Carlos Morales identify as Latinx; Oluseyi Olaose is Nigerian; and Riann Ramkissoon-Hardeen is Yemeni-Indian. Some of them are immigrants themselves, while others were born in the United States. Some have undocumented parents. Others have parents who are U.S. citizens or have green cards. Some graduated this year — Riann headed to Bates College in Lewiston, Maine; Carlos to Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin; and Esther is at Yale University in New Haven this fall.

How does the United States look to them? How did they interpret Trump’s campaign to restore American greatness?

“The chaos was always there,” says Riann. “We just never recognized it until a white supremacist came into power.”

There’s no sugarcoating it: the students’ view of the president — and the country — is bleak. Most describe a process of steady disillusionment with the United States, often one that began before the 2016 election.

Oluseyi says, “Coming from Nigeria, I had all these simple stories of what it was gonna be like … a happy place that, like, had freedom and justice and liberty for all. And then coming here and not experiencing that, and seeing the backlash and all the hate against people of color in this nation. I did not feel as though I should be part of such a community.”

Riann echoes, “I guess I never really thought of America as my community. I tried. I tried so hard to ‘fit into’ this society. And I never really found myself here.”

Nonetheless, the students talk about tears and shock on Election Day a year ago, hazy memories of a day clouded in disbelief. Esmeralda describes “having a meltdown” at school the next day. Her sister Esther describes crying for the better part of the day, and she can’t remember whether she made it to her morning classes.

Carlos says, “I think the country takes it day by day, hoping that this day is not our last day.”

The election changed Riann’s daily life. “Being an immigrant, my mom enforces that I walk around with my green card, because in my neighborhood, [immigration officers are] really prevalent … It’s scary to know that the nation that you once had so much faith in and your family came to for you to seek better opportunities is not necessarily that nation anymore. It hurts a lot, and I guess that’s how it’s going to continue.”

This is the paradox of America in 2017: the movement to make older white people feel that America is once again great has left America’s Future — diverse young adults — feeling anything but. And it’s built on an old formula: Populism is the combination of common anxieties with vulnerable targets into a driving current in the national political bloodstream. The reaction inevitably creates a new target, a fantasy that is both catalyst and byproduct. In There Goes the Neighborhood, immigration advocate Ali Noorani suggests that our contemporary political situation partly derives from the fact that many white Americans — many Trump voters — can’t find a satisfying answer to this question: “In a racially, ethnically, and culturally diversifying society, where do white Christians fit?”

America has proven to be decidedly unexceptional: our populists echo ethno-nationalists the world over when they argue that “Making America Great Again” means targeting immigrant families.

White Americans’ anxieties boil over in ugly ways. Recall, for instance, GOP Rep. Steve King’s worry that “our civilization” in the United States can’t be “restore[d]” with “somebody else’s babies.” Between such revealing outbursts, these fears usually simmer along with lines bemoaning the state of our Anglo-American heritage or “the Judeo-Christian West” or attacks on Islam.

In this telling, new arrivals imperil an Anglo-American cultural tradition that is purportedly essential to American strength. While radical ethno-nationalists flirt with arguing that Muslims or non-Europeans are somehow essentially unsuited to participate in U.S. democracy, moderate conservatives focus on immigrant assimilation. They argue that immigrants — particularly those from traditions somehow distant from the United States’ — must be taught the cultural trappings of democracy.

Even the moderate conservative position is prone to derailment. “We don’t have the same problem of assimilation [as Europe],” said The Washington Post’s Charles Krauthammer in an interview with Fox News’s Tucker Carlson after the June terrorist attacks in London. However, he warned, “the bilingual education fad” could provide domestic competition for America’s culture, leave immigrant communities insufficiently assimilated, and open the country to terror attacks.

Clownish as these arguments are, they’re related to a serious position. Democratic citizenship takes practice. Most of us would agree that American democratic institutions run on particular kinds of social capital. Most of us understand that there are behaviors that make our common life better — anything from responsible saving to volunteering, conscientious parenting, and regular engagement with neighbors. Surely American civil society would be stronger if newly arrived immigrants behaved in these ways.

Fortunately, they do.

Research suggests that the view of immigrants as alienated, culturally hostile community destabilizers could not be more empirically bankrupt. In one study, researchers found that “across the board, the prevalence of antisocial behavior among native-born Americans was greater than that of immigrants.” Immigrants were less likely to harm animals, start a fight, hurt someone on purpose, shoplift, or have their driver’s license suspended.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s comprehensive 2016 synthesis of research on U.S. immigration found that “greater concentrations of immigrants” were linked to “much lower rates of crime and violence than comparable non-immigrant neighborhoods.” Whatever the president claims about them, here in the real world, the factual world, immigrants tend to be model community members.

According to the report, they even have a uniquely “steadfast belief in the American dream.” And yet, through waves of insults, scaremongering, and even violence, Trump and his supporters seem determined to hammer that optimism out of them, to will an ugly caricature of immigrants into existence. They are creating that which they feared: a generation that does not feel part of the United States, that does not believe in the basic worth of the American project.

Trumpists may shrug at this; they may even nod along. The restoration of American greatness will be messy.

Their short-term political satisfaction is long-term political poison. When a movement dominated by white Americans treats immigrant Americans as enemies, these students take them seriously. The Trump Era is teaching them that they are not part of the American community, and that American democracy is dangerous to them.

Want to make them laugh? Ask them about the mindset and mechanics of making America great. Ask them to imagine being white in America and feeling as though you’ve been given a raw deal, feeling like the country needs to be rebalanced to give you a fairer chance. Their eyes pop. Ask them to suspend their disbelief for a moment just to get the whole construct of our present moment off the ground: America, we hear, has forgotten white people — particularly white men. Tell these debaters, these scholars who have deferred so much in order to pursue their college dreams, that white men in large sections of the country are angry that a high school diploma is no longer sufficient to earn them a stable place in the middle class.

The room explodes in bitter, incredulous hysterics. “It’s hard to say, ‘I’m going to compromise with you’ when you’ve had your way for so damn long … when does my day come?” demands Carlos. “Compromise is essential, but, like, right now, we have to get to their level first.”

“When you’re a woman or when you’re a person of color, you’re not going to be viewed the same as someone who’s white and straight and a man,” insists Riann. “You’re not going to be given the same opportunities.”

They keep coming back to safety. “The biggest fear that I have is that if you give people an inch, they’ll take a mile; they’ll see this very racist and prejudiced man as president and they’ll say, ‘Hey, we can do whatever we want,’ ” says Carlos. “People think that like, ‘Hey, I can take advantage of people because my president is in favor of me and not in favor of them.’ I think that’s just my biggest fear.”

I ask the students about their hopes in Trump’s America. Some talk about feeling alienated from their dreams. What chance can they have of a fair shake in a country that elected such a man?

See, these students have had to chase the standard path to success in American society harder than anyone — because of the significant structural impediments that society has put in their way. Students at their school are almost uniformly from low-income families of color. As people of color in America, as children of immigrants growing up in Brooklyn, they are given slim margins for error, more and higher obstacles to surmount, and fewer supports on their way. Nonetheless, they spend the school year traversing the Eastern Seaboard debating the Electoral College, gender equity, and a crowd of issues related to race and politics in America. Somehow, these students still care.

But they still expect to be “marginalized,” no matter how hard they work or how carefully they tread. They wonder about giving Trump what he wants — about leaving. Esther and Oluseyi fantasize about corners of the world where men are not allowed, where everyone is a person of color, places like Umoja, a mythical-sounding, all-female Kenyan village.

Why stay? How can they begin to build the lives they’ve imagined here, now? Esther’s father was deported before Trump was even elected. They talk about the bewilderment of meeting Trump supporters at debate competitions. The young Trumpists sometimes say that they disavow the president’s uglier rhetoric but still support his economic policies.

“If you’re voting for Trump, you’re voting for his views on social issues and refugees and immigrants,” Oluseyi says, exasperation in her voice. How, as an immigrant, or as a child of immigrants, do you begin to explain that to a white competitor who thinks support for Trump is simply a matter of lowering tax rates? Esmeralda is paralyzed: “I can’t change their opinions.”

See, Trump has detonated the processes of discourse that might help to rebuild connections between these groups. He cements what these students have long suspected: in America, they are inextricably defined by their identities. It’s not only that the students see no place for themselves in Trump’s vision of the United States. It’s that they recognize the United States in Trump. He is not an aberration. He is not a deviation from American norms.

Trump is the norm.

Esther is scathing:

I think the American dream, it doesn’t apply to us, just because we didn’t make the American dream. The concept of an American dream was created, for me at least, by white settlers who used, like, manifest destiny and westward expansion. Their American dream was basically, like, kicking people out of their land. And like, that’s not my American dream. You could argue that it’s the same today, well, it’s morphed into something more subtle … the American dream we see in movies or in shows or in books, it’s an American dream for white people … I think we could make a new version of the American dream if we wanted to, but just because of its history and the way that people have used it in the past, I don’t think it exists.

Since last November, Trump’s opponents have torn at one another over how to move forward. What, erm, happened? What lessons should the country’s liberals, progressives, leftists, and assorted Trump opponents learn from the election? Some — perhaps most notably the Times’s Lilla — have blamed “identity politics” for Trump’s rise. So the story goes, the left’s insistence on hearing and addressing grievances group by group does damage to our common American-ness, and/or de-emphasizes common problems facing economically vulnerable Americans, and/or alienates white Americans from Americans of color.

This is the conversation that many Americans want to have about Donald Trump, American democracy, and the future. They usually argue that Trump’s coalition can only be stopped by sublimating the concerns of different racial, ethnic, linguistic, and/or cultural groups into a broader class-based politics that can tempt white working-class (especially male) voters.

There may be a rational case for this position. It may have significant political merits. It imitates Trump’s signature move: It would elevate the grievances and anxieties of white, working-class Trump voters without considering how that approach might land with young, diverse, immigrant Americans.

But these students, on the cusp of adulthood, see their identities — their genders, races, ethnicities, and immigrant origins — as the most important factors giving their lives meaning. In his 2017 account of the global rise of populism, Age of Anger, writer Pankaj Mishra warns: “Young members of racial and ethnic minorities, who awakened politically through the internet during the great economic crisis, try to protect their threatened dignity by insisting on being recognized as different.”

When these students talk of the country’s future (and its past), they see it almost entirely through the lens of identity. In the wake — and constant roil — of Trump’s rhetoric, “our country” narrows to match our tribes. “Our” country is no longer the common space, discourse, and society we share together, but the collection of those who resemble us.

“There are different Americas to different people,” Esther says. “There’s an America at school. At home, where we live, there’s an America. Wherever I go, there’s an America, because I was born here, my sisters were born here. My mom could technically be an American, because she’s lived most of her life here, but she’s still undocumented, so … Trump supporters don’t make America my home. They are the trespassers here.”

So: Leave aside the internal coherence of the arguments for abandoning identity politics for a moment. Leave aside the political implications and any electoral calculations experts might make. Instead, imagine how these students hear such arguments. Consider how their shared and overlapping identities feel like their safeguard and shield.

Naturally, this story is too neat by half. Those frequent interviews of Trump’s base have repeatedly highlighted surprising (to reporters based in coastal cities, at least) examples of generosity to immigrants living in small Rust Belt towns. Perhaps they are skeptical of immigrants, but they cherish José and Sofia’s family that lives down the street. Coin the hashtag: #NotAllTrumpVoters, or at least #NotAllTheTime.

Similarly, the students periodically talk of finding ways to engage with Americans from Trump’s coalition. Even the most critical, disillusioned students talk of working harder for justice, of engaging to address the country’s many sins. Riann talks of fighting to make equal rights a reality in the United States. Esther adds one category to her list of different Americas that transcends identity: “I think the people who genuinely believe in openness are Americans.”

Riann describes her American dream like so many young adults before her: “to go to college … becoming who I want to be. And now, with what’s going on with America, using my voice to change the America we have today.”

And even though Oluseyi declares, “I don’t believe in the American dream,” her personal project remains hopeful: “To give back to this community, basically. It hurts me seeing people helpless and like, I don’t like myself for not being able to do much about it … I want to be able to give back and make people have better lives, especially people who look like me, who haven’t gotten opportunities.”

But still, Trump opened a series of breaches in our common life; there is a gulf between his core supporters and these students. The United States’ national sins loom large in the students’ lives. They aren’t abstractions. They aren’t shadowy, faraway spectres “stealing” jobs or opportunities. They’re proximate, quotidian facts: parents deported, cars repossessed because the family paid a sibling’s college tuition bill instead of the auto loan, threats of police violence, daily indignities of integrating into American life, and countless other frustrations.

Against that backdrop, their persistence is as remarkable as their cynicism is predictable. Which leaves us in a bleak place. Populism that elides their identities could further alienate these new adults from the country’s economy, society, and culture. Long-standing demographic patterns, meanwhile, will continue to bring more children of immigrants into prominence in more aspects of American society — likely provoking deeper and more radical fears from Trump’s core supporters.

Now what? Might demographic trends settle the issue? As older, whiter Trump-supporting Americans pass away, they will be replaced by increasingly diverse generations. American pluralism is advancing, and Trump cannot stop it.

But, then again, these trends aren’t new. The United States has been getting more diverse for decades, and xenophobia, Islamophobia, and myriad other bigotries haunted the fringes of U.S. politics until Trump metastasized them into a unitary movement. Indeed, if rising pluralism helped spark cultural anxieties that brought Trump political success, it’s entirely possible — and even likely — that more pluralism will only add fuel to the fire. Just ask the residents of Charlottesville, Virginia.

No, demographic trends are no solution to what is ultimately a political problem. Increased American diversity may shuffle the political calculus for would-be heirs to the surviving members of Trump’s coalition, it but won’t single-handedly cure the country of the radicalized populism he has normalized.

The students know this, and they don’t dare get their hopes up when it comes to white Americans. “Just leave me alone,” says Carlos. “Trump took that veil off and [now] we’re fighting for … letting people live their lives.” Is this surprising? How should they feel?

We can’t dodge the debate. The tension between these groups is unsustainable — and bad for democracy. Whatever else it is, democratic life requires taking part in the processes of government, but not only in a government. It’s also about contributing to an economy, feeling part of a shared culture, and broadly engaging in the common work of living together. Democracy says: You count. You matter. You have a chance here, so long as you’re willing to trust in the basic political procedures that govern our community.

What next, when that trust is broken? Whenever it becomes viable, the solution is likely to follow two paths. The first has been most recently outlined by writer Eric Liu, who argues that the United States needs a strong historical core that includes, and sustains, a fuller account of American pluralism. Students like the ones I interviewed in Brooklyn feel as unrecognized in America’s past as they do in its present.

“A lot of our history is just not … it’s not there,” says Esther. “We have to dig deep for our history.” And while American history is replete with violence toward and marginalization of diverse voices, it also contains important examples of openness and generosity.

An honest account of American history is a prerequisite for building a better American present. Think of it as providing a common foundation for arguments over what the country should do next. Many of the United States’ current political divisions stem from the different accounts different groups of Americans have of the country they inhabit. An account of the United States that dispatches racism from the national scene with the end of the 1960s civil rights movement is an account that helps distance white Americans from non-white Americans who face it every day. The American story encompasses scenes both tragic and glorious; one way of bringing a more diverse country together is to ensure that the version we tell ourselves is as comprehensive and inclusive as possible. It needs to help everyone see themselves as part of a meaningful project.

But if a better, fuller public history is necessary, it’s also far from sufficient. Historians will not save the United States from the searing heat of partisan politics, let alone the bitterness of selfish anxieties. The second part of any effort to rebuild American discourse will necessarily rest upon building up new forums for debate in institutions that have not historically engaged on questions of diversity and immigration. In his book, Noorani describes meetings with pastors in a variety of churches in conservative towns and/or states. Faith leaders establish their moral authority by serving as trusted anchors for individuals and communities. When they speak out to affirm the importance of welcoming immigrants, they help bestow legitimacy on the rethinking of American cultural identity in a way that makes room for diverse immigrant families.

The United States needs more local institutions to engage in immigration conversations, broadly construed. Churches are not the only organizations that can serve this purpose, though they are often the best-placed to engage conservative Americans on moral questions related to immigration. Other familiar civil society lodestars — schools, health care institutions, athletic leagues, and more — can also lend their social capital to efforts to show how immigrants contribute to American communities.

Of course, any discussion of solutions is premature in a moment when the federal government is maintaining a “Victims of Immigration Crime Engagement” (flagrantly acronymed VOICE) office “to acknowledge and serve the needs of crime victims and their families who have been impacted by crimes committed by removable criminal aliens,” a moment when things look likely to get worse before they improve. Each day brings fresh fuel for our fears.

The president’s regular assaults on basic norms of democratic governance make it hard to trust public institutions to deliver stable, predictable, supportive decisions. Meanwhile, the seeming stall of Trump’s legislative agenda — and the ongoing headwinds from his campaign’s connections to Russia — prompt the president to constantly seek out ways to bolster support from his base. For that purpose, nothing serves quite as well as ugly rhetoric about the “dangers” of Muslims in the United States and around the world, or the supposed insecurity of the country’s border with Mexico.

The United States has not yet ceased harming its public institutions and the cohesiveness of its society. It took years to build the trust currently being frittered away. When hardworking children of immigrants on the cusp of attending college, on the very brink of seeing their years of playing by the rules pay off, when students like these doubt the value and fairness of working within the American system, this is as good a signal as any that the real dangers of Trump’s populism will take years to work out.

America’s future growth and prosperity increasingly depend on children of immigrants. According to the Urban Institute, “Children of immigrants accounted for the entire growth in the number of young children in the United States between 1990 and 2008.” They will make up most of the growth in our workforce in the coming decades. The United States’ future looks much more racially, linguistically, ethnically, culturally, and religiously diverse than its past — or even its present.

Esther is deeply aware of the stakes: “I need the country to be redeemable,” she says. “What other place in the world is going to uphold democracy? I mean, we’re not upholding it now, but … one man cannot be the destruction of every single thing that my people have died over.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)