As Free College Tuition Becomes a Popular Rallying Cry, ‘Tennessee Promise’ Hailed as Game Changer — but Equity Concerns Remain

Tiptonville, Tennessee

Lake County, population 7,500, the bubble-shaped piece of land in Tennessee’s northwestern corner, is wrapped by the Missouri River that separates it from two bordering states. Tiptonville, its biggest town and county seat, has a state prison and a small tourist attraction noting the birthplace of rockabilly legend Carl Lee Perkins, best known for writing and releasing the original “Blue Suede Shoes.”

Lake County is also the state’s poorest: Nearly 43 percent of adults and 49 percent of children live in poverty. Further, it’s the least-educated county in the state; less than 12 percent of adults have at least an associate’s degree.

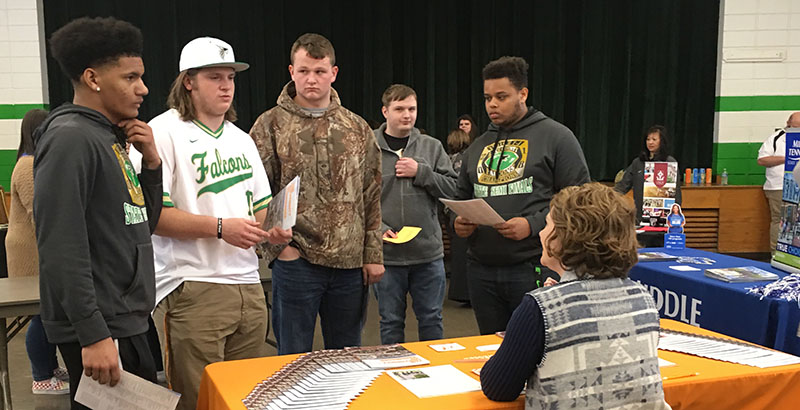

That’s the challenge facing Michelle Johnson and Tonya McKellar, the counselors at Lake County High School, who are trying to push the 45 members of the class of 2019 to continue their education. An essential part of their arsenal has been Tennessee Promise, a four-year-old program that covers tuition and fees at community college or technical school for any high school graduate in the state.

“It’s just the whole culture that we have to change, and that’s not just the students. It’s the county. It’s the parents. It’s everybody,” McKellar told The 74 during a visit in mid-December.

The program is part of former governor Bill Haslam’s “Drive to 55” initiative to get 55 percent of Tennessee residents to earn a college degree or certificate by 2025. The broader program, which also now includes free community college for adults without degrees, was initially billed as an economic development and workforce initiative to, as Haslam put it, “ensure Tennesseans get Tennessee jobs.”

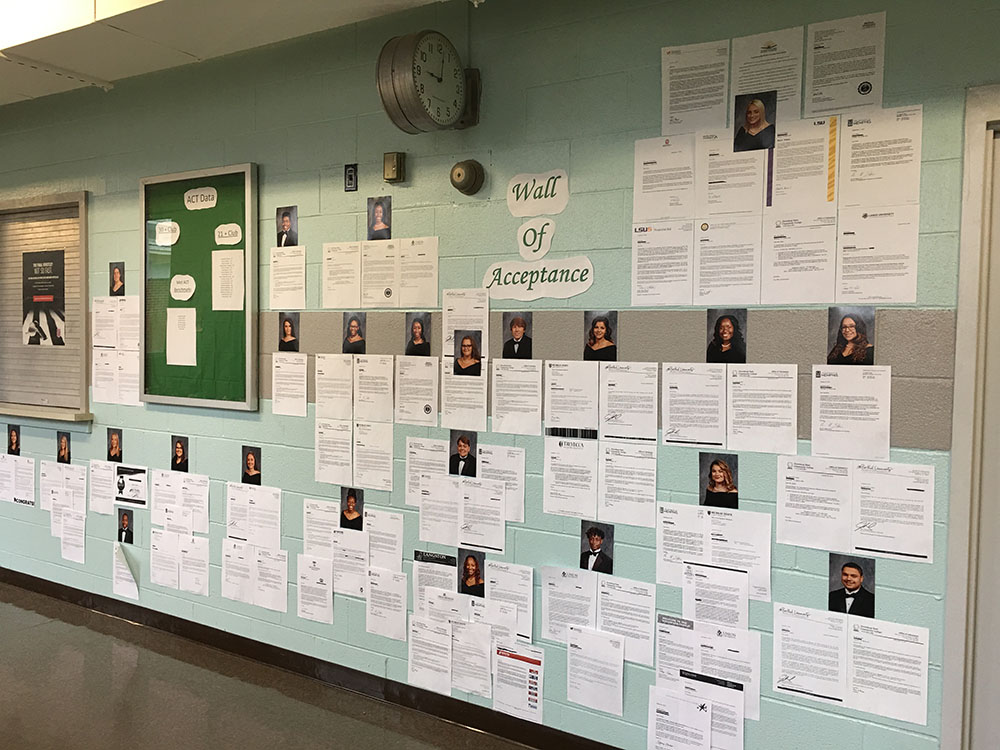

But Tennessee Promise is also having an impact earlier in the educational pipeline, changing the college-going culture in the Volunteer State’s high schools, both rural and urban, advocates and counselors told The 74.

“I think Promise has been a game changer for the culture in high school. It’s no longer about if, it’s about where you’re going to college,” said Krissy DeAlejandro, executive director of TNAchieves, a nonprofit that runs the program’s required mentoring and college orientation programs in much of the state.

“We often hear from students who say, ‘I’m the first one in my family to go to college, and now my siblings want to go to college,’” she said.

The program is increasingly being looked at as a national model, as other states emulate and expand on Tennessee’s example and progressives have made free college tuition a political rallying cry.

Even within the state, the idea of “free college” recently became even more expansive, when the University of Tennessee in March announced free tuition at three of its campuses for students who meet certain academic requirements and whose families make less than $50,000 a year.

Though widely praised — including by former president Barack Obama, who sought to replicate it at the federal level — Tennessee Promise does have its critics, primarily those who say its benefits primarily flow to students from higher-income families rather than those most in need. Undocumented students aren’t eligible, and research has shown lingering equity gaps despite the program’s near-universal accessibility.

The class of 2019 is just the fifth eligible for the program, so research on its impacts on students’ K-12 experience isn’t yet available. A study of a similar program for students in Kalamazoo Public Schools in Michigan showed that it resulted in more credits earned, higher grades and fewer days in detention or suspended in high school, particularly for African-American students.

Across Tennessee, 63.4 percent of the class of 2017 enrolled in higher ed the fall immediately after graduating from high school, up 5 percentage points from the class of 2014, before the program began.

“More kids are thinking they can have the opportunity to go to college with the Tennessee Promise, where they wouldn’t have before,” said Johnson, the counselor at Lake County.

The program, the first in the country to offer nearly universal access to all graduates, has been a lifeline for students who didn’t take their academics seriously early in high school, said Yolanda Grant, a counselor at Ridgeway High School in Memphis for the past 12 years.

“We don’t want them to think that because I didn’t do my very best in ninth, 10th and 11th grade, I don’t have any options. So with the Tennessee Promise, they still have an option,” she said.

State higher ed officials don’t keep track of recipients’ class rankings or high school GPAs, but they have seen that students in the program tend to have ACT scores “on the lower end,” said Emily House, chief policy and strategy officer at the Tennessee Higher Education Commission.

Research that House and her colleagues at the state agency presented to the state legislature in March 2019 also showed that the rate of remediation in Tennessee colleges is on the rise, which she attributed to the expanded attendance pool, including those who got lower ACT scores.

Although many of those low-scoring students would’ve enrolled in college before Tennessee Promise, more are doing so now that community college is increasingly accepted as part of the higher ed landscape, she told The 74.

“At the student level, it’s shifting this level of conversation around what it means to go to college,” she said.

‘They didn’t know what they were missing’

Johnson and McKellar, the Lake County counselors, are zealous about completing applications for Tennessee Promise.

One hundred percent of the class completed the basic application forms before The 74’s visit in mid-December. The eight stragglers who hadn’t finished the federal financial aid application required at all colleges, and for Tennessee Promise, did so by the Feb. 1 deadline.

That effort to complete the Tennessee Promise application, with its early deadlines, means students benefit even if they don’t ultimately use the program, McKellar said.

“It gives you a mindset of ‘We’re all working together to get to a certain point,’ and it all gets done early. That’s a big push,” and it has helped students earn other scholarships, she said.

The push has made students more receptive to college in general, Johnson said. “I think before, they didn’t know what they were missing.”

Johnson and McKellar expect 60 to 70 percent of this year’s class to go on to some form of higher education. That’s up from the 43.1 percent of the class of 2017 who went immediately to higher ed, according to figures from the state Department of Education.

About half of the class of 2017 who went to higher ed attended community college, and the counselors say that’s likely to continue, with many headed to Dyersburg State Community College, a 30-minute drive from downtown Tiptonville.

Many students will use their two free years as a springboard to a four-year degree.

Johnson’s own daughter, who initially intended to spend all four years studying pre-K-3 education at a four-year school, decided to take advantage of the two free years at Dyersburg State before transferring.

But the opportunities come with a downside: Sending students out of Lake County for higher ed often means they won’t come back.

“There’s not a lot in Lake County, not a lot of opportunities in Lake County for folks with degrees” outside of education, Johnson said. “We have some very successful folks, but the majority of them stay out of Lake County.”

Though Johnson and McKellar encourage all students to maintain their Tennessee Promise eligibility, just in case of changed plans or family circumstances, only about 20 percent will actually use the grants. Many students, who come from very low-income families, will instead be covered by federal Pell Grants, Johnson said.

Tennessee Promise is what’s known as a “last-dollar” scholarship, meaning it covers tuition and fees only when other financial aid has run out. Pell provides up to $6,095 per year depending on family need. For many of the lowest-income students, Pell covers all the tuition and fees that would otherwise come from Tennessee Promise grants, so they don’t see any financial benefit from the program.

That lack of help to the neediest students is among the primary criticisms of the program. Advocates have argued that limited state dollars should be better targeted to the lowest-income students — for example, by paying for four-year degrees or helping with housing and living expenses that exceed Pell awards.

State officials say the lowest-income students do benefit.

“I understand the logic, because yes, these [Pell Grant-eligible] students don’t get [state] dollars. But I think even the lowest-income students get so much from this program,” including help filing their financial aid applications, mentoring and a general stronger college-going culture, House, the state higher ed official, said.

In an ideal world, all free college programs would be “first-dollar” and cover all college costs without considering other aid a student may receive, “but that is very rarely going to be politically feasible, financially feasible,” House added.

Both Johnson, at Lake County, and Grant, at Ridgeway, said they’ve helped low-income students who have encountered that problem. In the end, they say, it doesn’t particularly matter to the students where the money is coming from, so long as they get it.

Statewide research, on the other hand, showed that while the rate of community college completion has risen dramatically in the wake of Tennessee Promise, relatively few low-income students enroll in postsecondary education, and wide racial gaps in degree completion remain.

Physical access to Tennessee Promise-eligible schools has been an issue, too.

The northwestern corner of the state is particularly disadvantaged. Only 29 percent of Lake County residents have access to a community college within 25 miles, according to state figures.

Dyersburg State Community College, the most popular choice for Lake County students, is the closest, and students can also use Tennessee Promise to attend two nearby colleges of applied technology.

But beyond those schools, Lake County’s unique geography means that community colleges in bordering Missouri and Arkansas are closer than many in-state, Tennessee Promise-eligible schools.

State higher ed officials are keeping track of those higher ed deserts, House said, and are working with some K-12 districts to keep the buildings open for adult education offerings.

‘A backup plan’

It’s not just in rural Tennessee that the program is making a difference.

In Memphis, students at Ridgeway often say they had a plan to go to college but weren’t really putting anything into action before the additional push from Tennessee Promise, Vice Principal Taurin Hardy told The 74.

“Now they’re doing it. Now they know they have that financial stability, that financial backing. That’s a huge barrier for a lot of kids, especially kids of color,” he said.

For students who don’t need that extra reassurance, the program can also be something of a fallback.

As of mid-December, Alexis Jefferson, a Ridgeway senior, had been accepted into two four-year colleges where she hopes to study business and marketing, on her way to a job advertising toys. But if those don’t work out, she can use Tennessee Promise to study at Southwest Tennessee Community College.

“It’s sort of like a backup plan,” she said.

Such attitudes are a distinct shift from the early days of the program, when Tennessee Promise was a difficult sell, Grant, the Ridgeway counselor, said.

Students were put off by the stigma of community college as “13th grade” and not real college.

“Now it’s easy. They know that ‘I have an option. Although my parents may not be able to afford college, I can still go.’ For a lot of them, this is their No. 1 choice … They know they can still get a quality education,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)