Why the Kids in My School Move from Class to Class — as Young as Kindergarten

Principal's view: It's a revolutionary approach for K-8 that our students and teachers really like — and could help close pandemic learning gaps.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

It’s been more than three years since the pandemic upended schools, but students are still living with the consequences. The continuous stream of news highlighting low achievement, stalled recovery efforts and chronic absenteeism is mind-boggling. Schools must fight to regain what’s been lost and help students regain their academic footing.

At San Tan Heights K-8, my team and I are looking at every aspect of how we educate students. Among the most important changes we’ve made is departmentalizing our teaching teams by subjects in grades K-8. Our grade-level teachers are now specialists, and our students rotate between classrooms — starting in kindergarten.

Departmentalization isn’t a big deal in middle or high schools, but it’s rare in elementary settings and virtually nonexistent in the early grades. Making the shift meant altering schedules, getting the children used to transitioning from class to class, building new professional development programming and more. Working with Great Minds, a developer of high-quality curriculum, we started two years ago with third grade and up. At first, the teachers were nervous. But soon they were feeling less scattered, more focused and better at their jobs. Now, the whole school operates this way.

The morning starts with an advisory, or homeroom, lasting about 20 minutes and focusing on social and emotional learning. This sets a positive tone for the day. The homerooms are led by our math, reading and English language arts/social studies teachers, so when advisory ends, students stay in that room for their first academic class.

Each grade level has three class rotations, and each class lasts 86 minutes. In kindergarten through third grade, one dedicated reading teacher works across grades on foundational skills. There is one English language arts teacher per grade, who also provides social studies instruction, and one math instructor, who also teaches science.

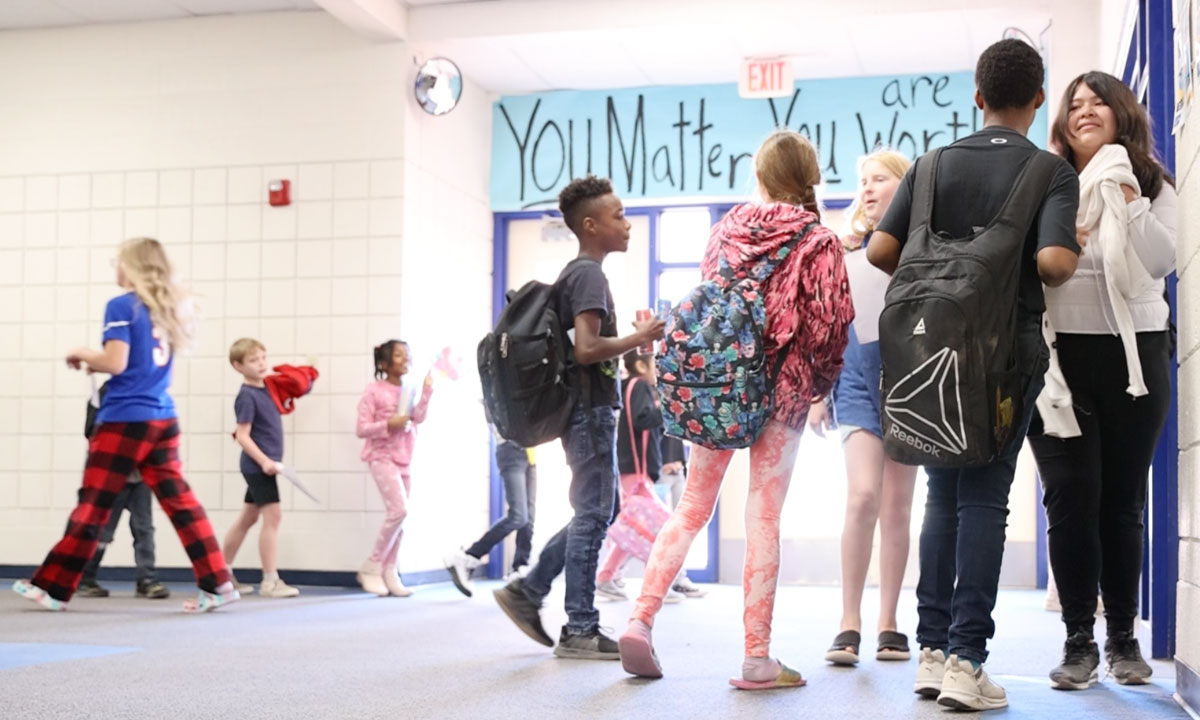

Every grade is divided into three cohorts, and these groups of children move from class to class together. We keep the transition time short, just about two minutes, to limit distractions and misbehavior in the hallways.

So far, the preliminary evidence indicates the change is producing positive benefits. For the first time in our school’s history, we experienced the highest growth in our district in both English and math, and I believe departmentalization has played a key role.

We’ve also seen improvements in our school culture and climate.

Students enjoy rotating classrooms during the day. It gives them a chance to move. And because they’re traveling together in assigned groups, they get to know one another well.

We had initially worried that teachers might have trouble building relationships with their students if they didn’t have the same kids all day. But we’ve found teachers can build great relationships with students if they have them for about an hour and a half a day and connect with them in meaningful and engaging ways on the subject at hand.

Departmentalization has also allowed educators to go deep into the subjects they teach and become the experts students need — especially given pandemic-related learning gaps. For example, our literacy teachers have been able to devote time to studying research related to the science of reading without feeling like they’re shortchanging other subject areas. Similarly, our math teachers have stepped back and studied our curriculum, received intensive coaching and learned new problem-solving and mathematical modeling approaches.

Our school, like many others, has replaced outdated curricula with higher-quality options, and more rigorous materials ask more of teachers. For example, they tend to require more time planning and preparing lessons. Departmentalization has given them that flexibility, and it allows our school leaders to tailor professional development offerings to their specific needs, based on the content they teach. They also get more opportunities to build their knowledge and collaborate with peers who teach the same subject in the grades above and below theirs. This allows teachers to explore how content builds upon itself from grade to grade.

As a result, teacher satisfaction is on the rise, leading to increased retention. Our school’s usual attrition rate has usually been around 30%, but in 2022-23, it dropped to 13% percent. Also this past year, half of the open positions at the school were filled by teachers within the district who requested to transfer in. That has never happened before.

Our teachers are happy because we’ve made them partners in the restructuring. Their input was critical when determining which educators to assign to each subject, a decision that also involved data showing which were the most effective. Once we moved to departmentalized instruction, I encouraged teachers to share feedback on how things were going as we progressed. Their insights have informed our practices — which are being evaluated by researchers from Johns Hopkins University over the course of a five-year study.

For elementary school leaders interested in departmentalizing, my advice is: Try it. You can always switch back if it doesn’t work, but I doubt that will happen. We at San Tan Heights welcome the chance to share what we’ve learned and help more schools close pandemic-era learning gaps by adopting this revolutionary approach. It’s well past time to rethink what schools are doing and take steps that can make a big difference in young lives.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)