Campus Road Trip Diary: 8 Things We Learned This Year About America’s Most Innovative High Schools

Reporters at The 74 fanned across America to find some of the nation’s most inventive and personalized high schools. Here’s what we learned.

Just over two centuries ago, the first boys — yes, they were all young men — walked through the doors of Boston’s English Classical School, the first so-called “higher school” in America, willing subjects in an experiment that revolutionized education as towns and cities rushed to open their own high schools.

English Classical and its imitators proudly proclaimed their ability to prepare students for new jobs in emerging, high-tech industries such as banking, manufacturing and railroads.

It’s just over 200 years later, and high schools have opened their doors to all teens, not just boys. But with technological disruptions daily changing our conception of what a well-educated young person looks like, Americans are again clamoring for innovative secondary schools that help them make sense of these changes. They’re looking, above all, for institutions that leave behind many of the traditions of the past in favor of offerings that promise to help their kids get a strong start.

Since last spring, journalists at The 74 have been crossing the U.S. as part of our 2023 High School Road Trip. It has embraced both emerging and established high school models, taking us to 13 schools from Rhode Island to California, Arizona to South Carolina, and in between.

It has brought us face-to-face with innovation, with programs that promote everything from nursing to aerospace to maritime-themed careers.

At each school, educators seem to be asking one key question: What if we could start over and try something totally new?

What we’ve found represents just a small sample of the incredible diversity that U.S. high schools now offer, but we’re noticing a few striking similarities that educators in these schools, free to experiment with new models, now share. Here are the top eight:

1

They don’t worry about what came before.

In these places, high school looks almost nothing like it did for our parents or grandparents.

While the seven-period, books-in-a-locker high school, with its comprehensive curriculum, vast extracurriculars and Friday night football games is alive and well and available to most of the nation’s 17 million or so high schoolers, it is no longer the default model.

Instead, thousands of young people now attend high school each morning in facilities that more closely resemble workplaces, professional training grounds and research labs. Quite often, young people are in actual workplaces for part of their school day, either as apprentices or taking part in something resembling career tourism, trying out jobs to see what fires their imaginations and fits their tastes.

2

They focus intently on exactly what their students need.

Most of these schools are small by design, so the traditional mission of serving thousands of students with countless courses — as well as the requisite menu of after-school activities, such as sports, music, and drama — is out of the question.

In its place, many new schools now offer one key thing: focus. Intense, unrelenting focus.

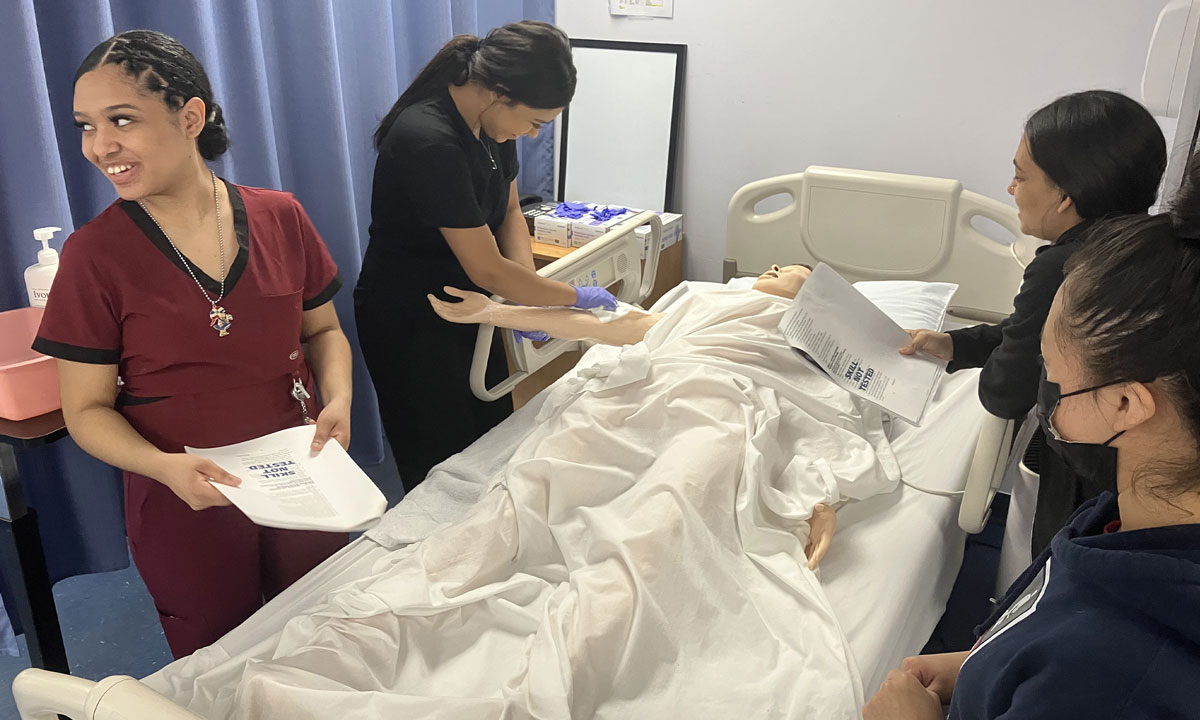

At Rhode Island Nurses Institute Middle College in Providence, R.I., students show up for class each morning dressed in scrubs. They spend four years learning the bedrock values and basic skills of the nursing profession, earning college credit before they graduate.

The school’s laser-like focus is perhaps its greatest strength, said Principal Tammy Ferland, a veteran educator. “This is a health care program, a nursing program,” she said. “If you don’t want to be a nurse, if you don’t want to be in health care, then you don’t belong here.”

Students can still play sports or perform in the band — they just need to find those things at their neighborhood school or elsewhere —after they remove their scrubs.

The same focus is on display at Urban Assembly New York Harbor School on Governors Island, a ferry ride south of Manhattan, where the East River meets the Hudson. Students must choose among eight maritime-themed career and technical education pathways before they close out their freshman year.

Clad in life vests, protective goggles and welders’ masks, students get a chance to earn industry certifications in marine science or technology before graduation — bona fides that help them enter the workforce or pursue further education.

Most of its students come to the program with an interest in marine biology research, environmental science and aquaculture. And while many pursue these fields, others migrate to ocean engineering, professional diving and even vessel operations.

3

They embrace internships and personalization.

Many of these new high school models focus less on one industry than on imparting what students need to know about the modern workplace more broadly, through intensive, often personalized, coursework and professional internships.

At Blue Valley Center for Advanced Professional Studies in Overland Park, KS, students spend about three hours a day working with professionals in one of six industries, from food science to aerospace engineering.

Housed in a light-filled, three story building that more closely resembles a high-tech office, the program enjoys support from the local school district, which created it as a half-day program that serves only juniors and seniors.

Students return to their neighborhood high school for required coursework. For accreditation purposes, the district treats the entire enterprise as a class.

“Blue Valley CAPS treated me like a working adult,” said alumna Sophia Porter, who now holds dual degrees in physics and applied mathematics and statistics from Johns Hopkins University and serves as a project manager and test operator for BE-4 engines at the Texas aerospace company Blue Origin.

At The Metropolitan Regional Career and Technical Center in Providence, students spend much of what would typically be class time working on personalized projects prescribed by advisors, who follow small groups of just 16 students throughout their high school career, intimately learning about their interests and academic needs. Students also spend much of their four-year career in a series of bespoke internships at local businesses, nonprofits and educational institutions.

Founded in 1996, The Met is renowned among a brand of progressive educators seeking to create small, personalized high schools around students’ passions and interests. “That’s what the Met taught me,” said Jordan Maddox, class of 2007. “Don’t really limit yourself.”

Maddox admits he initially didn’t quite know what to make of the place. “I remember telling my mother, ‘Mom, this is a daycare for high school students.’ And she was like, ‘Give it a chance. Give it time.’”

These schools also offer a kind of freedom and agency to students that would have been unheard of to their parents.

At One Stone, a tiny private high school near downtown Boise, Idaho, students are deputized to run much of the operation, serving as officers of the board and filling two-thirds of board positions overall.

“A lot of people don’t believe that high school students can do meaningful, big things,” said Teresa Poppen, One Stone’s executive director and co-founder. “And I have always believed that they can do meaningful things when empowered and trusted.”

Or, as recent graduate Abella Cathey put it, “Being treated like an adult is what makes you act like one.”

4

They prepare young people for jobs in emerging industries.

Just as the first public high school offered to educate young people to compete in the high-tech industries of the era, the new breed of high school offers the same promise, only in medicine, aerospace and tech-assisted agriculture.

In Lodi, Calif., as the number of wineries begins to match its status as a major grape-growing powerhouse, the nonprofit San Joaquin A+ has partnered with the Lodi Unified School District and others to create an internship pipeline that gives students real-life learning and experiences across a variety of roles in the winemaking industry.

The partnership turns rural wineries into state-of-the-art classrooms where students spend time inspecting vines, cleaning storage tanks with pressure washers, and setting up tasting. In the end, they learn about the whole business: growing grapes, making wine and selling it.

Across the country, at Anderson Institute of Technology in western South Carolina, students from three districts now get real-world experience early on in their educational careers in preparation for jobs at companies like Bosch, Michelin and Arthrex.

Much like the Blue Valley model, students take core classes at their home high schools, and then commute to AIT to take classes like aeronautics, auto shop, and medicine. They work both in traditional classrooms and “labs” that mimic real-world work environments — an automotive garage, aerospace engineering lab or a surgery room.

“It’s all about giving kids a purpose in life,” said Don Herriott, a local business owner.

5

They’re rethinking what classrooms, campuses and school days look like.

In many new schools, such personalization takes place among new campus facilities, but in others, students navigate between several physical and virtual sites to attend class — sometimes all in the same day.

In Arizona, the 86 students who attend Phoenix Union City High School choose from a menu of some 500 options that include coursework at the district’s brick-and-mortar schools, its online-only program, internships, jobs, college classes or career training programs.

“The pandemic gave us an entree,” said Chad Gestson, until recently the system’s superintendent. “It enabled us to go to a system with no limits.”

Phoenix Union now operates four small high schools with specific themes, including law enforcement, firefighting, coding and cybersecurity. This fall, Phoenix Educator Preparatory welcomed its first students. It also operates standalone “microschools” housed in existing high schools — they include a program aimed at students working toward admission to highly selective colleges.

6

They redefine who high school is for.

Just as many schools now redefine what kind of space a high school should occupy, others are rethinking their customer base.

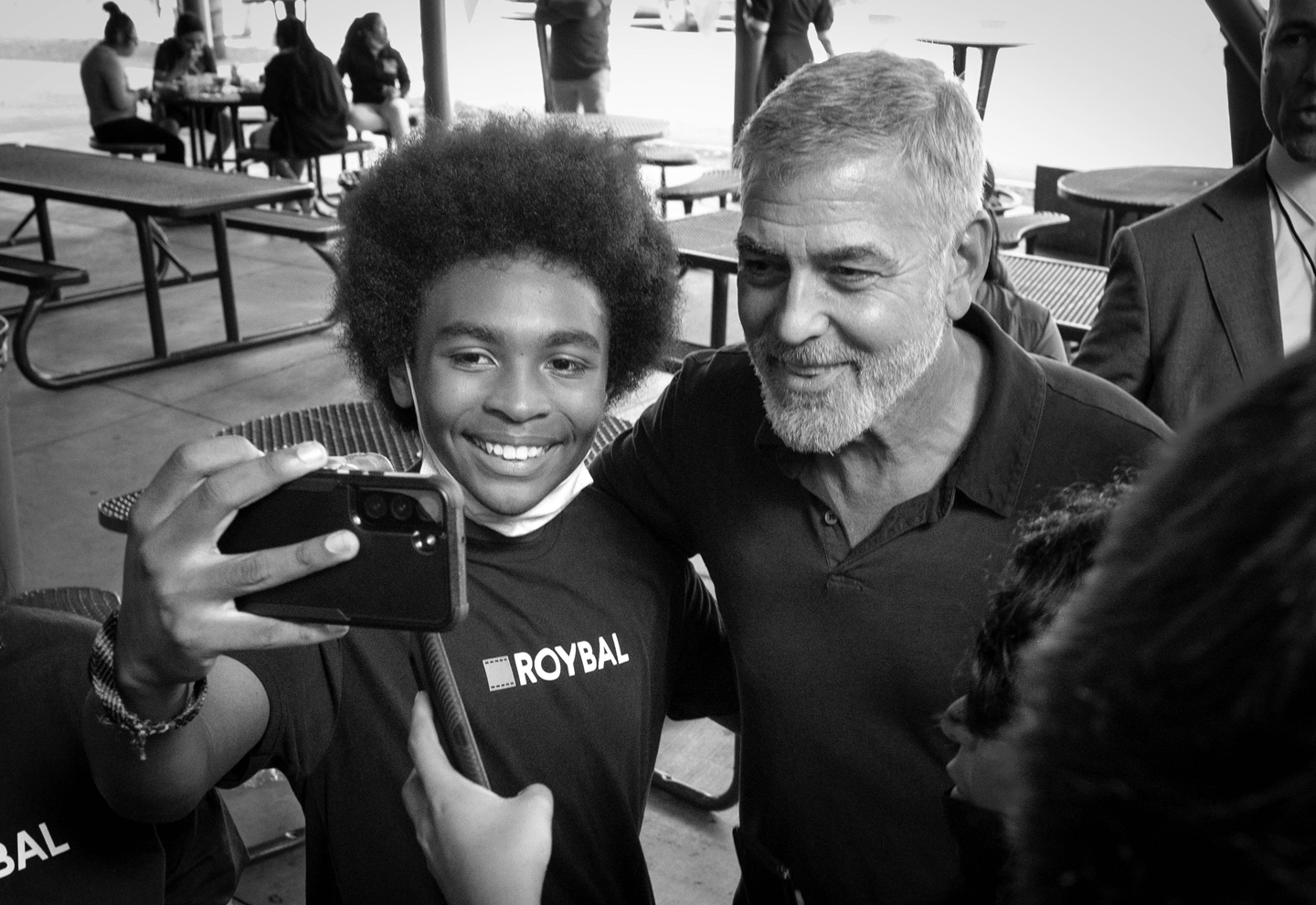

At Roybal Learning Center’s new film and television production magnet high school in Los Angeles, show business industry professionals last fall put up millions to launch a program to give Black, Hispanic and Asian students a pathway into good-paying jobs in the movie industry, helping them become “part of the machinery of storytelling,” said Bryan Lourd, an executive at Creative Artists Agency and the agent of actor George Clooney, a key supporter.

The school plans to match students with mentors in the industry and eventually develop an apprenticeship program to offer early experience in their chosen field. The goal, said Deborah Marcus, who manages education efforts at Creative Artists Agency, is for graduates to not only land their first job on a crew, but their second and third as well.

7

They serve students of color in a more supportive way.

At New York’s Brooklyn Lab School, social workers visited nearly 100 homes to find students as absenteeism soared after the Covid pandemic.

More than three years later, each Lab School student now has a personal advocate, an advisor who starts each day with a non-academic meeting to build relationships and discuss health or current events over free breakfast.

Two teachers now lead each class, at least one of whom is special education certified, as the school adopts an all-inclusion-model.

Morning office hours and a six-week night school offer more chances for students to bridge academic gaps made worse by the pandemic. And teachers are paid to lead and attend professional development sessions. Roughly 80% are Black or brown, serving about 450 students who are predominantly Black, Latino and low-income.

“When you’re a school of this size, you have the ability to respond and cater to the community that you’re serving, and be more personable with the families that you meet, the people that you work with, and the staff that you hire,” said assistant principal Melissa Poux.

8

They cut through traditional structures to find what works.

Perhaps most significantly, many high school programs are finding new ways to serve at-risk students.

For many, what they need most is more time to grow. At New York City’s Math, Engineering, and Science Academy Charter High School, recent graduates are paid $500 to participate in a six-week “13th grade” Alumni Lab that offers resume writing, interview support and sessions exploring growth mindset, self-awareness and making goals — skills that help young people, particularly alumni of color, work through feelings of inadequacy, shame, or feeling like an imposter.

“Life has not gone as they were led to believe it would,” said MESA’s co-executive director and co-founder Arthur Samuels. “…You have all of these kids who are not tethered to any institution, but the institution that they are tethered to is their high school. We need to leverage that relationship.”

The program last spring wrapped up its third cohort, with 71% of participants matriculating back to college or into a free workforce development program.

Schools, Samuels said, “create this artificial bright line that happens on the day of graduation: June 23, you’re our kid. June 24, we give you a diploma and you’re someone else’s problem.”

At Goodwill Excel Center Adult Charter High School in Washington, D.C., part of a network of Goodwill schools for adult learners nationwide, educators have compressed the traditional 20-week semester into a rolling series of eight-week terms. Coursework is based on competency, not seat time, and four assessments over the course of each term keep students on track.

But those who don’t succeed, even with individualized tutoring, can simply start over again at the end of eight weeks. Students with heavy work or family commitments can stay enrolled by taking just one class per term.

“We like to put high school dropouts into a box and say, ‘This is why they’re a dropout,’” said Excel’s Executive Director, Chelsea Kirk. “But we don’t ever think about what structures caused that. We don’t ever think about ‘How could a school change its structures to embrace people?”

— James Fields, Beth Hawkins, Linda Jacobson, Marianna McMurdock and Jo Napolitano contributed to this report.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter