‘We Have First-Graders Who Can’t Sing the Alphabet Song’: Pandemic Continues to Push Young Readers Off Track, New Data Shows

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Young children learning to read — especially Black and Hispanic students — are in need of significant support nearly two years after the pandemic disrupted their transition into school, according to new assessment results.

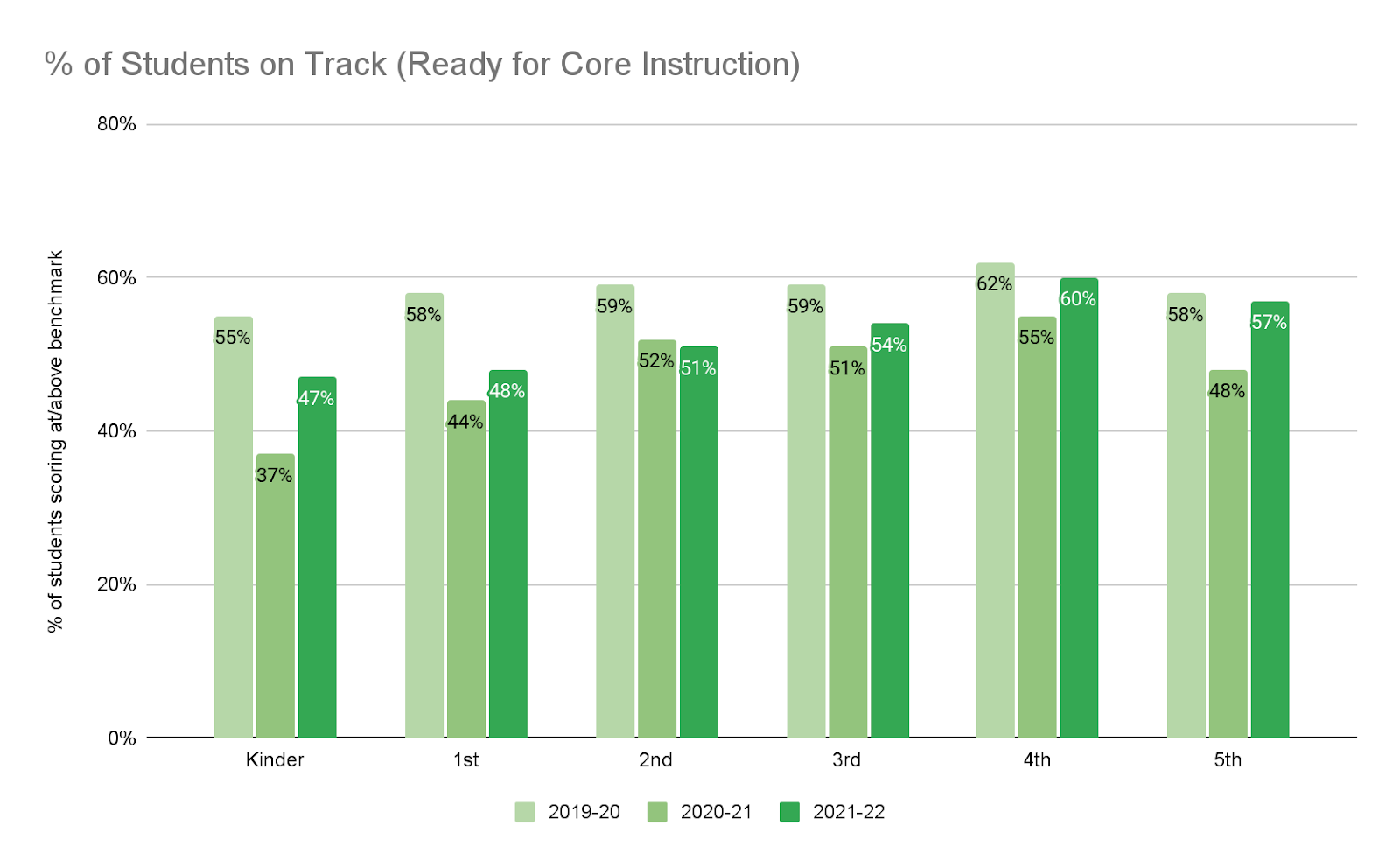

Mid-year data from Amplify, a curriculum and assessment provider, shows that while the so-called “COVID cohort” of students in kindergarten, first and second grade are making progress, they haven’t caught up to where students in those grade levels were performing before schools shut down in March 2020.

At this point in the 2019-20 school year, for example, 58 percent of first-graders were scoring at or above the grade-level goals. This time last year — when only about half of the nation’s schools were offering full-time, in-person learning — 44 percent of first-graders were on track. Now 48 percent are reaching the benchmark.

Results from fourth- and fifth-graders, however, show greater recovery, with the rates of students meeting benchmarks nearly back to the same level they were in the winter of the 2019-20 school year.

“Learning disruptions had a significant impact on our literacy outcomes,” said Susan Lambert, chief academic officer of elementary humanities at Amplify. She added that this year’s quarantines and short-term closures have likely contributed to the slow progress. “For the youngest learners to go to school for two or three days and then be out for 10 — it’s not just picking up where you left off; it’s actually starting all over again.”

Whether they skipped kindergarten and pre-K or spent much of their school years learning over Zoom, students in the primary grades didn’t have a normal introduction to reading. Educators note that less time to build vocabulary skills through socializing and disparities in children’s home lives — some had parents who read to them every night while others missed out — have contributed to the gaps. But reading experts and tutoring providers say they’re seeing students make strong gains with one-on-one support. The pandemic, they add, has only brought greater awareness to a persistent challenge.

“What has happened in the past couple years is more dramatic, but it’s not anything new for us who work in early literacy. Children have been struggling with reading for years and years,” said Kate Bauer-Jones, who runs Future Forward, an early literacy and family engagement program that works with districts in Alabama, Georgia and Wisconsin. The program recently received a $14 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education to expand to eight more states.

State-level efforts to improve reading instruction continue to spread, but Kymyona Burk, senior policy fellow for early literacy at the Foundation for Excellence in Education, said it can take two to three years before districts start to see gains. Schools, she said, also need to identify children who might have learning disabilities and provide parents with materials to use at home.

She added that even when children returned to in-person learning, social distancing from peers and teachers still got in the way of listening and speaking, which contribute to early reading skills.

The Amplify data also shows racial disparities, with Black and Hispanic students in K-2 not making as strong of a comeback as white students and gaps growing larger than they were before the pandemic.

Amplify assesses students with DIBELS, or Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills — a widely used measure of early reading development. The results are drawn from a national sample of 400,000 K-5 students from 1,300 schools in 37 states, allowing the researchers to compare pre-pandemic and current performance. While the schools in the research sample are more likely to be in large urban areas — and spent a longer period on remote or hybrid learning — Paul Gazzerro, Amplify’s director of data analytics, said he’s seeing similar performance across all schools using its assessment, which he described as “sobering.”

DIBELS itself doesn’t involve a lot of reading, but helps to predict how well children develop literacy skills by testing how fast and accurately they identify words, explained Rachael Gabriel, an associate professor of literacy education at the University of Connecticut.

She agreed that racial gaps in the early grades are widening and that “students are coming into K and 1 with different sets of skills” than before the pandemic. But at the same time, schools are “doubling down” on remediation and using both virtual and in-person tutoring programs to help students catch up.

She urged parents without access to tutoring to keep reading and writing with their children.

“This doesn’t solve the problem,” she said, “but it’s a protective factor that makes students more resilient” when instruction doesn’t match their needs.

Future Forward’s tutors are seeing those needs up close.

“We have first-graders who can’t sing the alphabet song,” Bauer-Jones said. “We’re seeing first graders coming in with no familiarity with text.”

During remote learning, her tutors mailed magnetic letters, books and literacy materials to children’s homes. But even if students consistently participated in Zoom sessions, those were “in no way, shape or form equivalent to in-person learning,” she said.

In fact, she added, tutors don’t see much difference in skills between young children who skipped pre-K or kindergarten in 2020-21 completely and those who spent much of that year in virtual learning.

Now that students are back in school, Bauer-Jones is concerned about the second graders who have “never had a normal school experience,” she said, asking a question also on the minds of most teachers and parents: “What in the world are we going to see from those kids when they hit the third grade benchmark next year?”

‘Undoing the trauma’

Many of this year’s third-graders also missed key opportunities to become stronger readers, said Jessica Sliwerski, CEO of Open Up Resources, a nonprofit curriculum provider, and founder of Ignite Reading, a virtual tutoring model that offers students 15 minutes of one-on-one help over Zoom during the school day. Now in California, New York and Massachusetts, the program will serve 1,000 students by this fall.

Sliwerski acknowledged the challenges of expanding tutoring, but noted that depending on volunteers can limit a program’s success. Her tutors aren’t volunteers; they make $20 per hour.

“You can’t affect sustainable change through reliance on volunteers,” she said. “I want people who might go work in an Amazon warehouse to come be a tutor.”

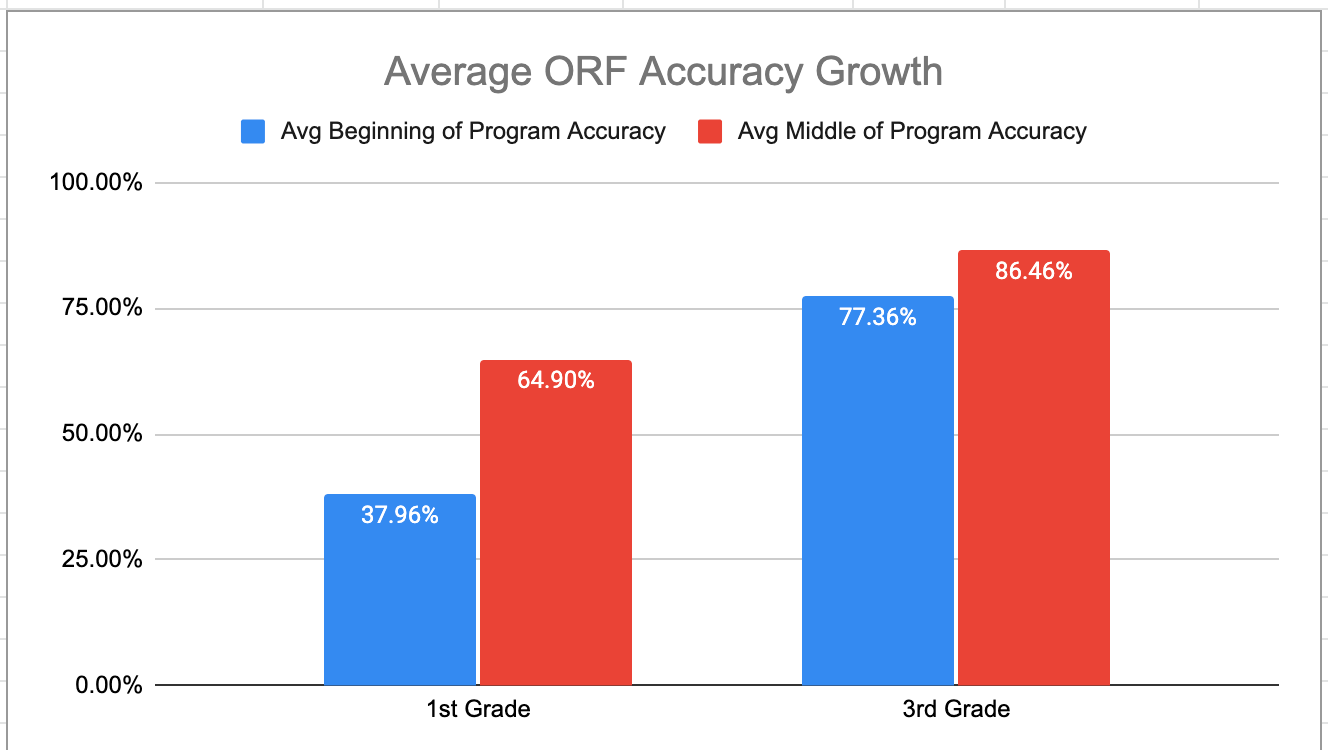

She recounted how In October, some third graders tested at kindergarten and first grade levels, when by the end of first, they should be automatically recognizing words and reading them fluently.

Results from a pilot program at Kipp Bridge Academy in West Oakland showed that when tutors began working with the third graders on decoding skills, they responded with 77 percent accuracy on a DIBELS “oral reading fluency” test. After 53 days, their accuracy increased to 86 percent.

Sliwerski called the growth “powerful.”

“It’s changing their identities as readers and undoing the trauma that they brought into the program when they said things like, ‘I’m not a good reader’ and ‘I hate reading,’” she said. “This group of students will not necessarily leave us on grade level, but will leave us as stronger, more accurate decoders.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)