Report: With Omicron, Math App Zearn Reveals a Troubling New Gap in Student Engagement — Even Where Schools Are Open

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

When COVID-19 forced school closings in March 2020, Shalinee Sharma was among the first to document the pandemic’s disparate impact on student learning. Zearn, the nonprofit she co-founded, collects real-time data on use of its math app, which is used by one in four U.S. elementary students. So she could see that kids in affluent places were rebounding or zipping ahead, while those in low-income communities languished.

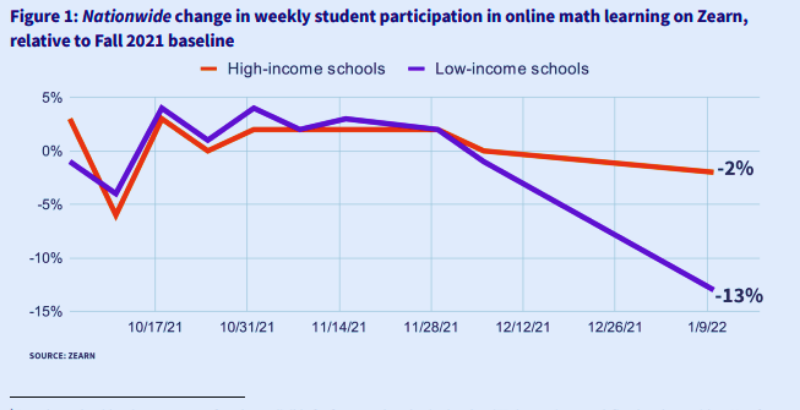

Since the start of the current school year, the gap had been closing, but in December, the Omicron variant sent school systems back into disarray. Between Nov. 28 and Jan. 9, Zearn use among students in prosperous school districts fell 2 percent. In school systems with concentrations of poverty, however, it plunged 13 percent.

Dramatic, yes, but the next discovery was the bigger surprise. While students who were able to attend school in person have better weathered the pandemic academically, Sharma was stunned to see that Zearn’s new data did not correlate to places where schools had shifted to distance learning because of the variant.

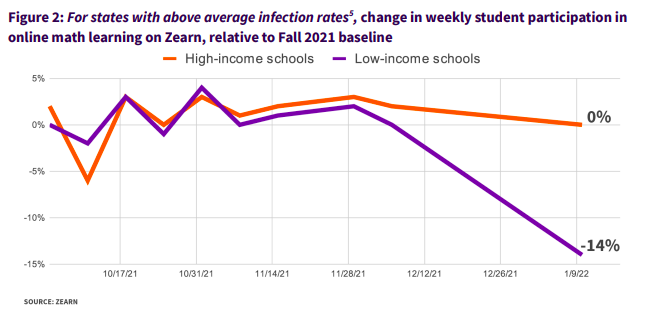

This time, the gaps appear to be biggest where COVID-19 infection rates are highest.

“While schools are open amidst Omicron surges, students from low-income communities are missing critical instructional time,” the report states. “While Omicron is everywhere, its inequitable effects are not.”

It’s a preliminary snapshot, Sharma says, but its implications merit immediate attention: Keeping schools open for in-person classes is not enough. Schools need better plans for preventing new disruptions from interrupting student learning. Zearn’s researchers aren’t certain what’s happening, but they have suggestions about what education leaders should consider.

“Districts that have remained open have experienced high student and teacher absence rates, either because they or someone in their family has contracted the virus or they have needed to quarantine for exposure,” the Zearn report notes. “In many districts, particularly those that serve students from low-income communities, the digital divide continues to exist.”

Separate research has found that up to 12 million students still lack reliable internet connections. And while school districts have spent billions in federal relief funds on technology, it’s not clear to Sharma that students have adequate access to them this year.

“Do these kids have devices at home if they need to quarantine, if their parents need to quarantine, if their teacher is sick?” Sharma wonders. “Because it looks like they don’t. Why aren’t they logging in? My wondering is, have we spent money but not actually solved the digital divide? Are they letting the computers go home? I think they’re not.”

The data Zearn collects remains one of the nation’s only real-time indicators of children’s math participation and achievement. Economists at Opportunity Insights, jointly run by researchers at Harvard and Brown universities, use the data as part of an economic tracker documenting the pandemic’s inequitable impacts on different socioeconomic groups.

The 74 last year took a deep dive into how the Opportunity Insights data was showing up in schools. Academic assessments, surveys of student and educator mental health and other sources of information have since backed up many of the predictions researchers made in those stories.

When the gap yawned open again in December, Zearn researchers first compared locations where app use had plummeted against a closure tracker maintained by Burbio, which catalogues disruptions to in-person schooling nationwide. Surprised to see no correlation, they tried the same exercise using the New York Times’ interactive case-count tracker — to a very different result.

In December, as Omicron’s disruptions were just beginning, McKinsey & Co. released an analysis that showed the achievement gap has widened by a third. Before the pandemic, students in majority-Black schools were nine months behind their peers. Now they are a full year behind.

The new disparity will compound existing gaps, Sharma predicts: “The kids who missed the most [at the start of the crisis] are now again missing the most.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation provide financial support to Zearn and The 74. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Chan Zuckerberg Initiative provide financial support to Opportunity Insights and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)