Early Reading Skills See a Rebound From In-Person Learning, But Racial Gaps Have Grown Wider, Tests Show

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The return of in-person learning last spring led to a boost in young children’s reading skills, but performance hasn’t returned to pre-pandemic levels and racial gaps have grown wider, according to new data from curriculum provider Amplify.

Compared to winter results, the end-of-year data on the widely used Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, or DIBELS, shows that fewer students were at risk of not learning to read — a decline to 38 percent from 47 percent in kindergarten and a drop to 32 percent from 43 percent at first grade. But the scores at third grade, a critical year for developing more advanced reading skills, haven’t bounced back in the same way.

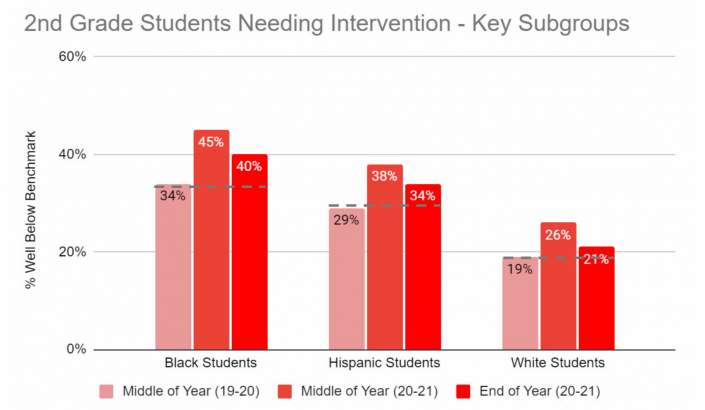

The results provide some hope that a full in-person return to school this fall could see young children quickly regain the early literacy skills they missed while learning from home. But students entering fourth grade might need more targeted support to get back on track not only in English language arts but across other content areas as well. In keeping with anecdotal evidence and other assessment results, the Amplify data confirms that the severe disruption in learning caused by the pandemic has disproportionately impacted Black and Hispanic students, but the setback for white students has been minor.

“It is really encouraging to see that when we get back to instruction, the kids in the early grades are really responsive,” said Susan Lambert, Amplify’s chief academic officer for elementary humanities. But the pandemic, she added, has magnified existing gaps in reading for Black and Hispanic students. And many in the upper elementary grades will need extra intervention from tutors, reading specialists and others specifically trained in literacy.

The racial disparities were also noted this week in an analysis of pandemic-related learning loss from McKinsey and Company, which found that while students ended the year about five months behind in math and four months behind in reading, students in majority Black schools had six months of “unfinished learning” in math and those in high-poverty schools were seven months off track.

In the Amplify report, the DIBELS data represents about 400,000 students from 1,400 schools in 41 states from both the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years. The sample also mostly reflects students in large, urban metro areas, which serve a higher proportion of Hispanic students than the nation as a whole.

Just prior to schools shutting down in early 2020, 32 percent of Black, 30 percent of Hispanic and 20 percent of white first-graders were severely off track. When the 2020-21 school year ended, 44 percent of Black and 38 percent of Hispanic first graders were significantly behind, but the proportion of white students in that range had increased by only 1 percentage point. At third grade, white students were even less likely to be well off track in reading at the end of the 2020-21 school year than they were before the pandemic.

Kymyona Burk, the policy director for early education at ExcelinEd, a think tank focusing on state education initiatives, said the results match the trends in students returning to school in person. Black and Hispanic students were more likely to finish out the year in remote learning, while white students returned at higher rates.

When students are learning to read in the classroom, teachers are better able to “check for understanding,” Burk said. But at home, a lot of students lacked a reliable internet connection, chronic absenteeism was high and even when students were attending remote classes, many turned off their cameras or didn’t want to speak on screen.

She added that for students who were already struggling readers, remote learning “was an easy way to check out of the process,” while more motivated readers probably weren’t deterred by the virtual format.

As districts decide how to plan recovery efforts this fall, Amplify suggested that it’s essential to collect data on students’ literacy skills and then to organize daily schedules and educators’ time to allow for extra reading instruction.

At last week’s Reagan Institute Summit on Education, Amplify CEO Larry Berger urged educators to take an informal inventory of students’ reading skills when school starts and focus on reestablishing relationships.

High-stakes assessments at the beginning of the year “could do more harm than good,” he said, but added it’s important to gather “enough data to understand where resources need to be deployed.”

This year, lawmakers in several states, including Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, North Carolina and Tennessee, have joined Alabama and Mississippi in passing legislation focusing on comprehensive literacy instruction, Burk said, adding that some are providing guidance on which materials to adopt and ensuring teachers are receiving training using those resources.

These laws, she said, improve equity for Black, Hispanic and low-income students since schools predominantly serving white and upper-income students were already offering high-quality reading instruction.

The Center on Reinventing Public Education’s review of district plans for using federal relief funds shows that several have prioritized literacy efforts. These include $25 million to hire and train 850 literacy tutors in grades K-5 in Chicago, a reading intervention coordinator in Maryland’s Montgomery County Public Schools, and elementary and secondary literacy specialists in Columbus, Ohio schools.

Both Lambert and Burk added that upper elementary teachers will need some support in how to teach foundational reading skills.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)