Union Report: Teachers Unions See Modest Membership Losses in 2018-19 School Year — Janus Decision Having Little Effect, So Far

Mike Antonucci’s Union Report appears most Wednesdays; see the full archive.

Active membership in both the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association took a slight dip in the first full year after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Janus ruling, which banned the union practice of charging representation fees to nonmembers who work in the public sector.

AFT reported 1,777 fewer working members than it had last year. The union’s total membership numbers were higher thanks to an increase of 8,546 retired members, who pay no dues.

Not all AFT state affiliates have reported their numbers yet, though the ones that did showed similar small changes in their membership.

On the plus side were AFT affiliates in Pennsylvania (up 492), Vermont (up 192), New Jersey (up 972), Ohio (up 823), Connecticut (up 600), Michigan (up 226) and West Virginia (up 442).

Affiliates that lost members included those in Missouri (down 33), Oregon (down 1,404), Massachusetts (down 574) and Rhode Island (down 267). The Illinois Federation of Teachers has not submitted its disclosure report yet, but its largest local affiliate, the Chicago Teachers Union, is down 507 members. The Louisiana Federation of Teachers reported 14,246 members in the first disclosure report it has ever filed. The Texas Federation of Teachers continues to report exactly 40,000 members, as it has every year for the past six years.

The National Education Association has yet to file its disclosure report, but last month, national union officers were informed that total membership was down 23,218 compared with September 2018.

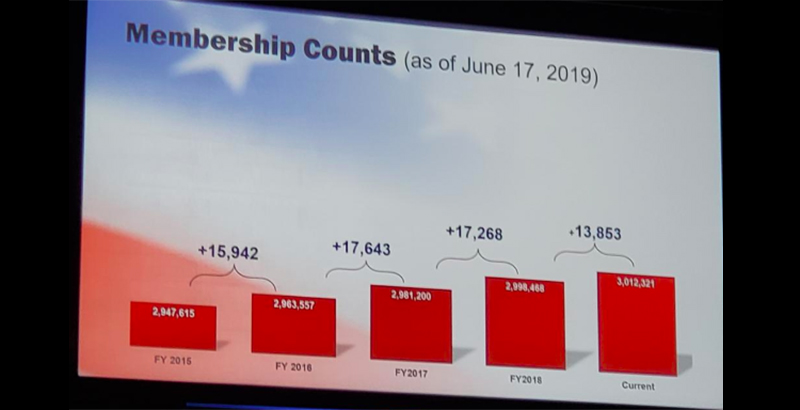

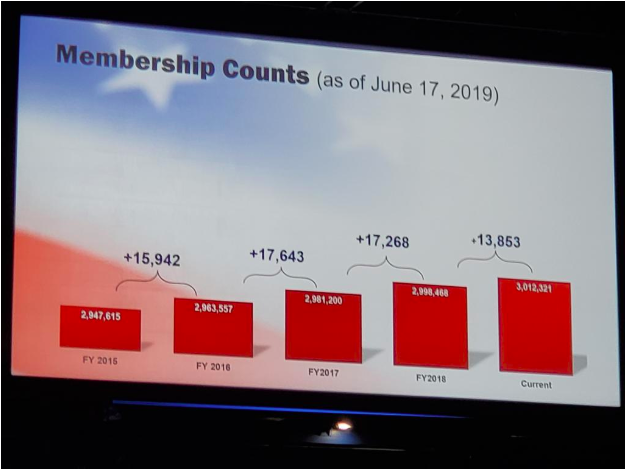

You may recall that NEA reported a membership gain to its delegates at the union’s annual representative assembly in July in Houston.

This is due to the union’s practice of comparing the current year’s numbers from June to the previous year’s numbers from September. As you might imagine, teacher union membership grows during the school year and drops when it’s over, which is when most education employees retire, leave teaching or are allowed to resign their union membership. Such seasonal variations dictate that June should be compared to June and September to September.

NEA’s total membership stands at 2,975,250. This figure, and NEA’s losses, require some context.

First, the lion’s share of the drop was due to the disaffiliation of the California Faculty Association and its 19,000 members. NEA adopted a bylaw amendment this summer to ensure that such secessions are much more difficult to carry out.

The remaining 4,300-member NEA loss is comparable to AFT’s loss, when the relative sizes of the two unions are considered. Only one NEA state affiliate, the Illinois Education Association, has filed a disclosure report. It reported a gain of 228 active members.

Considering the apocalyptic predictions that were made after the Janus ruling — mostly by union advocates — these modest losses have to be heartening for both AFT and NEA. But there are still worries, and there are things about NEA’s numbers we still don’t know.

Total membership is useful to know, but retirees can skew the tally. Hypothetically, if 100,000 teachers retire and they all become retired union members, total membership remains the same, but the union loses a lot of money and considerable clout in the day-to-day operations of schools and education policy.

Lest we forget, NEA also added a new membership category last summer that doesn’t include working education employees — “community allies.” How many joined in the first month of eligibility?

Finally, no examination of public-sector union membership should be made without considering the size of the workforce. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the local government public education workforce, which would include the vast majority of teachers union members, grew by almost 49,000 workers compared with September 2018.

It is never a good sign for unions when the workforce grows and membership shrinks.

It will take a lot more data and probably a few more years before we get a complete picture of the Janus effect. If I had to make an immediate assessment, I would say it hardly changed the ratio of members to nonmembers. Members stayed members, and nonmembers didn’t join. Of course, that ended up being a net loss of revenue for public-sector unions in the former agency-fee states, but there was no mass exodus, even after accounting for short resignation windows.

The place where unions will win or lose is among new teachers and education employees. Now that new workers can freely choose to be nonmembers and keep their money, can unions recruit them in sufficient numbers to replace retiring members?

If not, the unions will need a larger pool of potential members from which to draw. That means pushing for more staff hiring or expanding into more professions outside of teaching. I expect we will see more of both in the next few years.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)