Unexpected Student-Discipline Trends in California: Suspensions Peak in Middle School, Black Kids More Likely to Be Disciplined in Segregated Schools & More

There’s been heightened awareness and activism in recent years surrounding the discipline gap, or the occurrence that minorities — black males in particular — are disproportionately suspended or expelled relative to other racial and gender subgroups. But what’s received less attention are some of the other surprising trends embedded deep in data out of California.

Black males in California public schools are suspended at a rate 3.6 times that of the statewide average for all students, according to a 2018 report by three education professors at San Diego State University and the University of California, Los Angeles.

While this comes as no surprise to those in the know, data suggest that certain factors affecting suspension rates have gone unnoticed, such as school size, a school’s racial makeup, and the way schools’ grades are structured — whether K-5, K-8, middle school, or high school.

● Among schools that suspend a disproportionate number of black students, school size tends to correlate with suspension rates. The rates of suspensions for black students went up as school size increased.

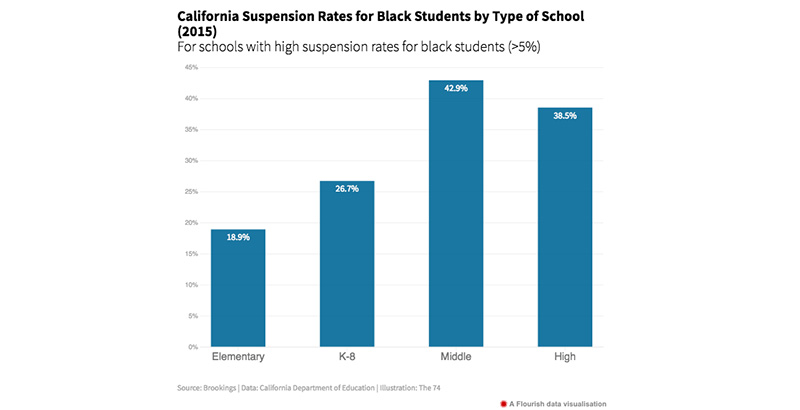

● Suspension rates for black students tend to peak in middle school and then fall in high school.

● Black students are more likely to be suspended when they attend segregated or “racially isolated” schools than when they attend majority-white or mixed-race schools.

“So much of the debate centers on whether schools are being too dismissive or overly punitive, and factors like school structure, which data show correlates to suspension rates, tends to get overlooked,” said education policy expert Tom Loveless, who produced a 2017 report on California suspension rates for the Brookings Institution.

His report examined out-of-school suspension data from the California Department of Education. The data covered three school years — from 2012-13 to 2014-15. Schools serving fewer than 50 students, schools for students with disabilities, alternative settings, and juvenile delinquent facilities were excluded from the numbers.

The school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, earlier this year sparked a national conversation and movement about the need to balance school safety with discipline policies that aren’t overly punitive.

That debate is still playing out. Recently, a group of 80 educators and student advocates signed a letter urging U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos to keep the guidance President Barack Obama issued in 2014, which called on school districts to reduce the use of suspensions and take action to close the gap in suspension rates between white students and their black peers.

Loveless’s research suggests there are factors within school districts’ control that impact suspension rates but have little to do with actual discipline policies. One factor is school size, particularly middle schools. Loveless noted that school size could be adjusted by reassigning students to different schools or building new ones.

Nearly 43 percent of middle schools in California suspended blacks at a high rate, according to Loveless’s report. That figure drops to below 39 percent in high schools. In elementary schools, it’s the lowest, about 19 percent.

The data don’t offer a definitive answer for why suspension rates are highest in middle school, but Loveless said it may have to do with the fact that middle school is typically the first year students have passing periods between classes.

“That’s when kids get squirrelly. It’s just a few minutes, but it gives kids time to get in trouble,” he said.

It’s also, of course, when students first experience a surge of hormones and have to navigate a complicated social maze toward adulthood. Data show suspension rates generally fall after 10th grade as students mature, Loveless said.

It’s possible that students with the most serious behavioral problems transfer to alternative or continuation schools at some point during high school, which are not reflected in the data. In California, students can leave school once they turn 16 if they graduate or pass a high school proficiency exam, similar to earning a GED. Those students wouldn’t show up in the data either.

It could also be a function of school size. Data suggest that larger schools tend to suspend students at higher rates, and some California middle schools serve between 2,000 and 3,000 students.

“You put 3,000 13- to 14-year-olds together, there are bound to be problems. Big schools are tough to manage,” Loveless said.

He found that small- and mid-sized schools suspended black students at below-average rates, while a larger share of big schools — those with 1,300 students or more — have above-average suspension rates.

Only 16.7 percent of schools that have 200 or fewer students have high suspension rates for blacks, defined by rates that are 5 percent or higher. That jumps to 38 percent for schools that serve 1,300 students or more.

The one caveat, he noted, is that there were schools where suspension rates couldn’t be determined because California does not provide data for small groups to protect student privacy.

Further, black students are more likely to be suspended when the percentage of black enrollment is higher. In fact, Loveless found the degree of racial segregation to be the strongest school-level predictor for high suspension rates.

About 23 percent of schools where blacks make up 6 percent or less of enrollment were found to suspend black students at high rates. However, 48 percent of schools that have the largest enrollment of blacks suspend them at high rates.

Again, the data don’t provide an answer as to why this is the case, but Loveless speculates that it could relate to the fact that segregated schools are more likely to be found in neighborhoods with layers of socioeconomic challenges like poverty and crime. These factors create trauma for students and could make them more likely to engage in disruptive behavior.

Segregated schools may also be more likely to employ less experienced educators who don’t know more effective techniques of dealing with challenging students, or who take a more punitive, “no excuses” approach to discipline and suspend students who fall out of step with school policies.

Loveless said that although characteristics like school size and, to a certain degree, segregation are within school districts’ control, school districts may be confined by financial and political constraints.

“Any time you try to break schools up and reassign kids to new schools, you’re going to get political pushback,” he said.

And in Los Angeles Unified, where more than half the students attend a school that’s more than 90 percent black and Latino, there’s only so much the district can do to integrate schools when the city’s neighborhoods themselves are segregated by race and class, Superintendent Austin Beutner recently said.

Suspension rates for black students may be at their highest in middle school, but the disparities start much, much earlier. Frank Harris III, a professor of postsecondary education at San Diego State University who helped produce the recent report on suspension rates for black boys in California schools, said he and his colleagues were shocked to discover that disparities emerge in early childhood.

In kindergarten through third grade, black boys are 5.6 times as likely to be suspended as the state average. Harris and his team then set out to interview community college students, asking what brought them there.

“The trends became apparent at the outset. No matter how we sliced the data, black males experienced the most exclusionary discipline,” he said. “Almost invariably, we would hear guys say, ‘I’m looking to improve my opportunities, and I had to go to community college because I didn’t meet the qualifications for four-year university.’”

The trends haven’t gone unnoticed by California legislators and school district officials, whose actions at the state and local levels have helped California reduce suspensions by 46 percent since 2011. But even as suspension rates have dropped across the board, the discipline gap hasn’t narrowed in any significant way for black students.

Thus far, the crux of the discipline gap debate has largely hinged on discipline policies or implicit racial biases among educators.

Still, Loveless said, he’d like to see educators and researchers broaden their views in the ongoing debate over school discipline and not look solely at policy.

“We need to understand the characteristics of schools that produce high suspension rates,” he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)