The Pandemic’s Virtual Learning is Now a Permanent Fixture of America’s Schools

Conor Williams visited nearly 100 classrooms in 3 states in the past 6 months and ed tech was everywhere

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

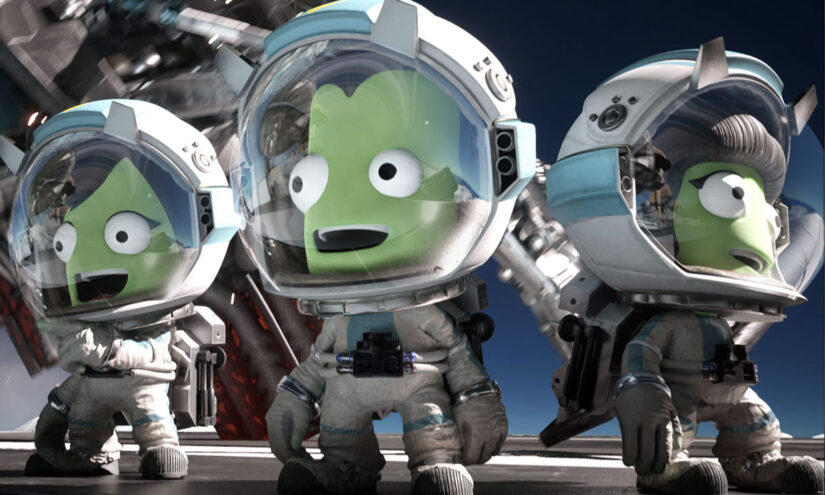

The rocket’s engine roars to life, and moments later, it slides up, up and up and away from the launchpad. An embedded video of the flight deck shows a worried, bug-eyed face behind the helmet visor — the astronaut’s pulling some G’s. He’s gone positively green. But wait — because this is a launch in Kerbal Space Program, a rocketry video game — the color isn’t a function of his stomach. No, he’s a Kerbal, and he’s literally green.

He’s also a star in Ben Adler’s 8th-grade science unit on gravity and kinetic energy at Oakland, California’s Downtown Charter Academy, a middle school in the city’s East Peralta neighborhood. Students are designing, building and launching rockets on Macbook Air laptops around their classroom — and trying to keep their “Kerbonauts” on track (and intact) for various space missions.

It’s clever, engaging and far more typical in 2023 than it was before the pandemic. Lessons like these mark a genuine shift in American schools. Indeed, though many campuses reopened in part during the pandemic because they concluded that children were not learning enough using digital tools during virtual learning, late pandemic schooling today is positively saturated with these devices.

Americans have spent huge chunks of the past three years thinking and talking about schools in binary terms — open or closed, in-person or virtual. But with schools all but universally open and back to a normal state (however imperfect), though, these dichotomies have gotten somewhat blurrier.

Truth is, we didn’t reopen schools back to “normal” in-person learning over the past few years … so much as we brought daily virtual learning into real-world classrooms.

It’s the new normal in U.S. public education — and it’s complicated. I’ve visited nearly 100 public school classrooms across three states in the past six months. I don’t recall seeing a single one without a computer screen projected onto the board at the front of the room. Lessons reliably include videos from curriculum vendors and/or the internet. On several occasions, I watched early elementary schoolers hold up badges hanging from lanyards around their necks to unlock laptops to play. Written assignments and quizzes — including Adler’s on rocketry — are often conducted on laptops and submitted online. As students type, teachers frequently project online timer videos with animated graphics and sound effects.

There’s no question that the pandemic shifted schools’ digital infrastructure. The extraordinary pressures of the past three years of crises forced significant new public investments in closing digital divides. Policymakers and schools poured emergency funding into purchasing devices like laptops, tablets, Chromebooks and internet hotspots so that all students would be able to access online lessons — so much so that supply chains couldn’t keep up. This made a real dent in longstanding digital divides, even if it didn’t wholly close them. Indeed, in January 2021, a survey of teachers still found 35% reporting that few of their English-learning students had reliable internet access.

It’s far from clear what this means for the present and future of U.S. public education. Teachers I’ve spoken with express ambivalence about the degree to which digital technology has permeated campus. Most say that it’s created both exciting skills and pernicious challenges.

When Downtown Charter Academy closed on March 13, 2020, it sent students home with two weeks of assigned work. As it became clear that the crisis was serious, DCA acquired digital devices and hotspots to ensure that all families could access distance learning. Within a few weeks, the school had moved its pre-pandemic schedule online. “It was 20 hours per day at first,” says Director Claudia Lee. “But it got easier.”

But closing device and internet access gaps was just a first step. Many DCA students and families lacked the digital literacy to use and manage these new tools. This was also true across the state. A fall 2020 survey of linguistically diverse California families found that nearly one-third of participants did not understand the pandemic learning instructions they received from their children’s schools. Further, fully one-third of participants responded that they did not have email accounts they could use.

DCA teachers say that the logistics of the transition were relatively smooth. They also confirmed that they faced many of the problems that plagued virtual learning across the country. Student engagement was a struggle, with some students attending only sporadically and others switching off their cameras under the pretense that their connection was too slow to bear the video. “We visited some homes,” says Lee, “and found some situations that were hard. Kids were trying to learn in kitchens, for example, or other places with lots of noise and distractions around. So we brought a small number of kids back to campus to log on virtually — but socially distanced.”

The school reopened for full-time in-person learning in fall 2021, but it was hardly a return to normalcy. By the end of that school year, DCA students’ academic outcomes were significantly stronger than peers in the surrounding school district, but that was only part of the story. In discussions during a daylong professional development session this January, many teachers noted that students were prone to online distractions and — worse yet — had become increasingly adept at using digital tools and resources to avoid doing their classwork themselves. Students brought these virtual learning habits back to their in-person classrooms.

“We need to help them understand that your choices become your identity,” said one teacher who asked not to be quoted by name. “Like, ‘If you always lie, you’re gonna eventually be known as a liar. If you always cheat, you’re gonna eventually be known as a cheater.’ George Santos is a great example of why you shouldn’t make lying a habit.”

And yet, these costs have attached benefits. Teachers are wrangling with new digitally infused questions around academic integrity, yes, but that’s also because they have continued to use Google Classroom and other platforms as part of their courses. These streamline student assignments, teacher grading and subsequent data analysis — and offer the potential for more effective and timely communication with students’ families. Indeed, teachers reported that, at this stage of the pandemic, many more of their families have and can use online communication tools like email, school communication apps (for example), and video conferencing to stay linked up to what’s happening on campus. In particular, Zoom parent-teacher conferences are much easier and more equitable than the old in-person-only model.

As such, teachers spent much of the family engagement part of the January professional development session discussing how to unlock families’ new digital literacy abilities. Members of the 8th-grade team admit to one another that they aren’t meeting their initial goal of reaching out to at least five families each week through the school’s official communication app — and brainstorm ways to reset and hold one another accountable to that expectation. The 7th-grade team agrees that they could do more to engage students’ families, and devises a process for making and sending a two-minute Friday video explaining what 7th graders will learn in the coming week. Almost everyone agrees that the school needs a meeting to help get families familiar with — and logged on to — the school’s different digital platforms.

As for the little green Kerbals in their spaceships, Adler emails, “Across all three days, no students were caught running any other program or browsing. A notoriously disengaged student became enraptured, and even turned in good marks on the follow-up assessment.” Students scored reasonably well on a subsequent quiz, with — for example — majorities of the 8th graders correctly identifying “apoapsis” as “the highest point in an orbit,” even though the term did not appear in any of the instructional materials other than the Kerbal Space Program missions.

So: is digital literacy a key skill (or a skill set)? Or are digital tools a crutch for students? Or some murky mixture of both? These are potent questions for this moment, as worsened teenage mental health, public launches of artificial intelligence tools and concerns about the state of the humanities are creating a national discussion about technology and education.

I truly don’t know. But I think we’re long overdue for a collective rethinking of just what we want from education technology. As we clamber out of three years of pandemic-steeped K–12 education, it presently feels like we’re drifting to a sleepy acquiescence of any and all digital learning tools without regard for their actual purpose. It’s time for educators, policymakers and families to adopt a more intentional, active stance when making education technology choices — with an eye to avoiding unreflective reliance on these tools.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)