The Pandemic Can Look Different in a Rural Area Than a Big City. Here’s a Breakdown from 2,500 City, Suburban, Town and Rural School Districts

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This essay originally appeared on the FutureEd blog

The COVID-19 pandemic can look different in a small rural school district than in a big city or suburb. Transportation challenges are often magnified with fewer students spread across wide areas. Internet access is frequently harder to find, and so are mental health professionals to support students and staff. Such challenges — and shared priorities — are reflected in a new FutureEd analysis of how local education agencies are planning to spend the latest round of federal COVID relief spending aid.

We used the National Center for Education Statistics’ four classifications of school district settings — city, suburban, towns and rural — to analyze the spending plans of nearly 2,500 school districts and charter organizations educating some 53 percent of the nation’s public school students. The information company Burbio collected the local agencies’ plans, which represent about $60 billion of the $122 billion in the third round of federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funding (ESSER III).

We found that staffing has emerged as a pandemic priority for local leaders nationally. Regardless of classification, more than half of all school districts and charter entities in the sample intend to spend relief funds on hiring and paying teachers and academic staff, and about 40 percent in each category expect to invest in teacher training. Similarly, at least half the local education agencies in every category plan to invest ESSER III funds in summer learning and upgrading ventilation systems.

But beyond those areas, priorities diverge.

Student Mental Health

City districts and charter entities are far more likely than their rural counterparts to earmark federal COVID relief funds for social-emotional learning, including curricula, materials and training, our analysis shows. The same pattern persists in large school districts (those with more than 10,000 students), most of which are in city settings. About 43 percent of city education agencies in the sample include spending on social-emotional learning in their plans, compared with 27 percent of rural districts.

City and suburban systems are more inclined to prioritize family and community outreach programs, as well. For example, the Santa Ana Unified School District, a 45,000-student city district in California, is planning to spend about $23 million, roughly 17 percent of its ESSER III funds, to support students and families with social-emotional health needs. American Preparatory Academy, a city public charter network with about 5,300 students on six campuses in Utah, intends to dedicate 16 percent of its ESSER funds, about $750,000, to social-emotional learning. The charter chose to target social-emotional learning after a survey found 85 percent of parents, administrators and staff considered it a priority.

By contrast, Powhatan County Public Schools, a rural district in Virginia with 4,300 students, plans to set aside less than 1 percent of COVID relief funds for mental health first-aid training. Most rural districts have designated less than 10 percent of their funds for social-emotional learning and mental health-related items. A notable exception is Bartow County, Georgia, which plans to spend $13.3 million, nearly 60 percent of its allotment, on mental health services and supports, in some cases through full-service community schools.

Similarly, rural districts are the least likely to prioritize hiring or paying mental health staff. About 42 percent of city districts and charter organizations plan to spend on mental health professionals or psychologists, compared with 29 percent in towns and 25 percent in rural areas.

The pandemic has certainly affected students’ mental health in small, rural communities and intensified opioid addiction and other rural problems. But as Allen Pratt, executive director of the National Rural Education Association, points out, there’s a dearth of mental health counselors in many rural areas, leaving districts unable to hire as many of the specialists as they might like.

Transportation

A greater share of rural districts remained open during the 2020-21 school year than in other settings, and there’s less support for going back to remote schooling in these communities, RAND Corp. researchers found. But getting students to school every day can be complicated by the long distances to school in some sparsely populated areas. Our analysis showed that rural districts are more likely to propose spending on transportation than education agencies elsewhere. About 38 percent of rural districts in the sample are earmarking ESSER III funds for transportation, compared with 21 percent in the suburbs, 28 percent in cities and 32 percent in towns. The shortage of school bus drivers affecting schools across the country may lead to more spending in this category in the months ahead than is reflected in agencies’ current plans.

In one instance, Marietta Public Schools in Oklahoma, a remote rural district serving about 1,100 students, is planning to spend roughly 21 percent of its allotment on transportation-related items. This includes $540,000 to purchase additional buses and $25,000 to purchase a van to transport food to a new building for middle and high school students. The district also plans to spend an additional $140,000 on new camera systems for its buses.

Academic Spending

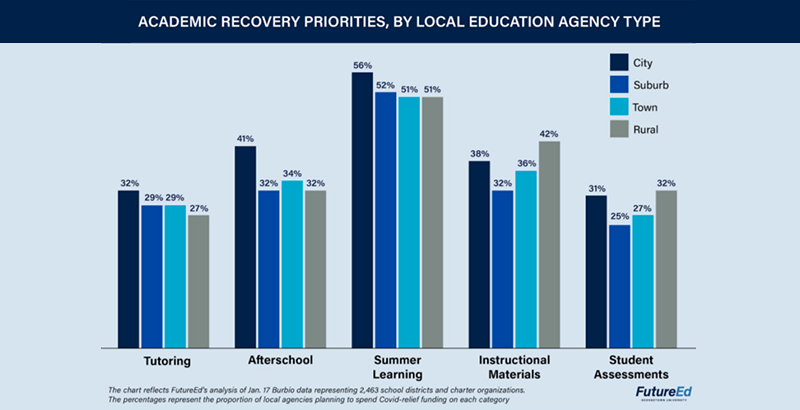

The transportation challenges rural districts face also may shape their strategies for helping students recover academically from the pandemic. Rural educators appear less inclined than those in other settings to spend ESSER III dollars on extended-day programs and more likely to spend the money on instructional materials and student assessments, the FutureEd analysis found.

Pratt says transportation challenges can sometimes limit the ability of rural school districts to offer afterschool programs, because it’s harder to arrange bus transportation after hours. He wasn’t surprised to see the proposed investments in instructional materials and software, and observes that with earlier rounds of federal funding putting mobile devices in the hands of more students and broadening internet access, rural educators now have more ways to reach their students.

For example, Hennessey Public Schools in Oklahoma, a remote rural district serving 833 students, is planning to spend almost $400,000 on classroom curriculum materials and textbooks, or about 13 percent of its ESSER III funds. In the town of Russellville, Arkansas, the 5,400-student school district intends to invest $1.4 million, also about 13 percent of its allocation in instructional materials.

In addition to investing in instructional materials, rural districts are planning to fund student assessment at a higher level than any of the other school district settings. Rural education agencies plan to spend $143 per pupil on student assessments, compared with $100 per pupil for town districts and charters, $61 for suburban agencies and $59 per pupil for city systems. Clinch County, a rural district in Georgia, is dedicating $1.9 million, or 45 percent of its ESSER III allotment, to “administering and using high-quality assessments” to assess academic progress and “assist educators in meeting students’ academic needs, including through differentiating instruction.”

At the same time, 41 percent of city districts and charters are planning to spend on afterschool programs, compared with 34 percent in towns and 32 percent in suburbs and rural communities. A slightly higher share of city education agencies and large districts are also planning to spend on tutoring, compared with 29 percent of local education agencies in suburbs and towns and 27 percent in rural areas.

Schenectady City Schools, a 9,700-student city district in upstate New York, plans to invest nearly $9 million of its $41 million ESSER III allotment in afterschool and extended day programs/activities, much of it delivered through local community agencies. Houston Independent School District in Texas is dedicating $75 million to provide before- and afterschool programs at elementary and middle school campuses, 9 percent of its total ESSER spending. And the suburban Fairfax County school district in Virginia plans to spend nearly $14 million, or about 7 percent of its total.

HVAC

At least half of the local education agencies in each category are planning to spend ESSER funds on updating and upgrading heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems. RSU 25, a small rural school district in Maine, plans to spend half its ESSER III allotment, about $1.3 million, to install a mechanical HVAC system in one of its four schools that previously did not have a system throughout the building.

In the town of Ukiah, California, the school district intends to devote about half its ESSER funding, $6 million, to upgrade and replace aging systems. Similarly, Newport News Public Schools in Virginia plans to spend $40 million, or nearly half its allotment, to replace HVAC systems in several schools and add air purifiers and filters. Suburban Montgomery County, Maryland, by contrast, has earmarked $6.6 million of its $262 million in ESSER funds for improving and upgrading ventilation systems.

Rural school districts and charter organizations plan to spend $559 per pupil on HVAC systems, compared with $495 for towns, $378 for cities and $340 for suburbs. The cost differences could reflect the economies of scale for education agencies in less-populous communities: HVAC work costs more per pupil when there are fewer students in a building. It also indicates a short supply of the materials and contractors needed to complete the projects.

Local education agencies nationwide are concerned that they won’t complete HVAC work by the September 2024 deadline for obligating ESSER III funds. That concern led AASA, The School Superintendents Association, the national organization representing school district leaders, to ask the U.S. Department of Education in January for an extension to the ESSER spending deadline for capital improvements.

At a time when students need help with academic recovery, spending on ventilation or transportation may seem beside the point. But the inclination of local leaders to invest federal aid in major capital projects may reflect the substantial infrastructure needs of the nation’s public school system.

While some policy experts warn local education agencies against spending the federal aid on new staff or salary increases that will be hard to sustain when the funding expires in 2024, spending on short-term mental health support or staff to reach out to students who have stopped attending school during the pandemic could pay substantial dividends.

Ultimately, policymakers need to know how — and how effectively — the federal money ends up being spent. But understanding how local education authorities in different demographic settings are proposing to spend a substantial percentage of the federal K-12 pandemic aid reveals the local agencies’ differing priorities, and their often sharply differing circumstances.

Phyllis W. Jordan is editorial director of FutureEd, an independent, nonpartisan think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. She is the author of Attendance Playbook: Smart Solutions for Reducing Chronic Absenteeism, released by FutureEd and Attendance Works. Bella DiMarco is a policy analyst at FutureEd. Research Associate Gunjan Maheshwari contributed to this analysis.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)