‘Essentially Abdicating Their Role’: Report Finds States Lack Plans for Ensuring Schools Spend Pandemic Aid on the Kids Who Need It Most

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

When Congress voted last spring to send schools an unprecedented $125 billion in COVID-19 relief funds, it laid down some basic guidelines. Most of the money should go directly to districts with an eye toward compensating for the pandemic’s academic and safety challenges, and states should track whether local officials complied.

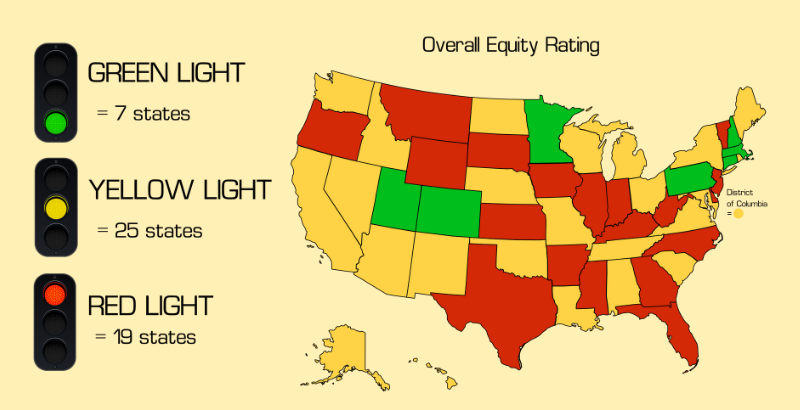

How well that’s going is “decidedly mixed,” according to a new review by the group Education Reform Now, which is part of a coalition of organizations advocating for the money to be spent on effective strategies to help the most disadvantaged kids. The group has created a dashboard rating states’ plans for spending their Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief — known as ESSER III funds, since it is the third round of federal COVID-19 relief money.

State education agencies receive only a sliver of the recovery funds but bear responsibility for making sure schools and districts make good use of the money. Yet Education Reform Now’s report details concerns that states are “essentially abdicating their role in ensuring equity and evidence-driven effectiveness in the learning recovery process,” noting that few have said how they will track implementation.

The report will be the topic of a panel discussion to be held online Wednesday, Jan. 26, at 2 p.m. Eastern Time. Education Reform Now’s Nicholas Munyan-Penney, who has closely tracked the spending plans, will be joined by New Jersey state Senate Majority Leader Teresa Ruiz, the Education Trust’s Terra Wallin, Education Reform Now’s Washington state Director Shirline Wilson and Christine Pitts, resident policy fellow at the Center on Reinventing Public Education. Registration is open now.

Earlier this month, the U.S. Education Department gave final approval to all 50 state ESSER III plans, as well as Washington, D.C.’s. But since districts have through 2024 to use the funds, there is time for states to take additional steps to ensure resources are being directed to the students and schools most in need and being spent on strategies backed by research, the new report explains.

A nonpartisan think tank affiliated with Democrats for Education Reform, Education Reform Now (ERN) was among nine advocacy organizations that drew up recommendations in May for how states could fulfill their obligations, as districts began creating the local plans that education departments were responsible for reviewing.

Seven states — Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania and Utah — earned ERN’s top “green” rating. According to the organization’s review, most states have failed to make sure funds are targeted to high-needs schools. Only half of state plans reflect “robust” efforts to solicit required input from community groups. And just six describe how officials will determine whether interventions paid for with recovery dollars are backed by evidence of effectiveness.

The third and largest relief fund approved by Congress since the start of the pandemic, the American Recovery Plan Act directs states to send 90 percent of their respective share of the money directly to school districts and public charter schools, which must spend at least 20 percent to address student learning losses and unmet social-emotional needs.

States are responsible for distributing the funds to schools and students most in need and to make sure schools use them for effective interventions. At least 5 percent of each state’s share of the money must also be used to address learning losses. According to ERN, 12 states are simply passing most or all of their share of the funds on to districts.

When Congress approved the first two rounds of COVID relief funding for K-12 education, school finance experts cautioned that districts would be tempted to spend the money on staving off layoffs in what was then presumed would be a devastating recession, plugging pre-existing budget deficits, giving staff raises and other things that would prove unsustainable once the money ran out.

As the pandemic stretched into a second academic year, it became clear that up to 3 million students were no longer attending public schools, which translated to a decline in state tuition dollars. States, the finance experts again warned, should be mindful of spending the infusion of federal cash in ways that create so-called fiscal cliffs — situations in which pushing a funding shortfall out into future years would worsen it.

At the same time, as researchers analyzed data on students’ flagging academic performance, a number of organizations made recommendations about interventions that would help students make up for lost learning quickly. Because the most profound gaps disproportionately affected historically disadvantaged children, the organizations — including the National Urban League, The Education Trust and the National Center for Learning Disabilities — said educators should take pains to see that resources were used to support those hardest hit.

In ERN’s survey, only five states — Idaho, Illinois, Massachusetts, Mississippi and Missouri — said in their plans that districts would be required to specify how they would allocate funds to their neediest schools. Because of this, education agencies will have a hard time holding districts accountable for prioritizing resources for low-income students, children of color, English learners and students with disabilities, the report notes.

Ten states will use a portion of the 10 percent of funds not going directly to districts to boost funding for school systems that do not enroll enough disadvantaged children to qualify for the main pot of ESSER III dollars.

There are bright spots, say ERN analysts. Nebraska and West Virginia have provided districts with roadmaps for the equitable distribution of funds, including using data on academic performance among different demographic groups to make sure they have identified the biggest needs.

And at least 20 states plan to invest in a kind of tutoring program that research has shown to be one of the most effective ways to boost student achievement. Arkansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Tennessee, Texas and Washington, D.C., have approved or are creating statewide tutoring programs.

As evidence that the plans can be used to pressure school systems to rethink local plans, the ERN report notes that many states revised their descriptions how they have engaged their communities as a result of the U.S. Education Department approval process. While nearly all states ultimately said they complied with the requirement that they consult with an array of organizations representing families and other populations rarely consulted during budgeting, it’s unclear how meaningful this engagement was.

On the positive end of the spectrum, the report singles out Colorado for hiring a consultant to host focus groups and survey community members. By contrast, Illinois insisted the consultation of stakeholders during the 2019 creation of a strategic plan counted, while Kansas pointed to early-pandemic task forces on distance learning and school reopening.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)