Texas Outshines California in its Approach to Teaching English Learners

Texas enrolls nearly 40% of its English learners — twice the rate California does — in some form of best-in-class bilingual education.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

“I see dual language immersion almost like language reparations,” said José Miguel Kubes. “There was harm done during those 18 years of English-only, and it’s our jobs as educators to do something about it.”

Kubes is the superintendent of Delhi Unified, a small district of five schools nestled in California’s Central Valley. Over 90% of Delhi’s students identify as Latino, around 40% have been classified as English learners and around 75% speak a non-English language at home.

Demographics like Delhi’s are relatively common in the Central Valley, whose agriculture economy has long depended on immigrants. Indeed, they’re reflective of California’s historical success attracting immigrants from a diverse range of cultures. This history is visible in the state’s K–12 system: there are just over 5 million English learners in the U.S., and more than 1.1 million of them are enrolled in California schools.

And yet, the state hasn’t always embraced this diversity — or the immigration driving it — as a strength. In 1998, as a capstone to a decade of anti-immigrant advocacy from Republican Gov. Pete Wilson, voters passed Proposition 227, a referendum banning bilingual education for nearly all English-learning children in California.

As Kubes notes, this was a disaster for kids. For nearly two decades, California schools stripped hundreds of thousands of linguistically diverse children of their emerging bilingual abilities. Worse yet, this was predictable: research suggests that bilingual and dual language immersion programs are the best models for these students to learn English and succeed academically.

This can seem counterintuitive: Wouldn’t students learn English fastest in programs that taught only in English? But a drumbeat of studies — and the experience of several other states — indicates that forcing young English learners into these sorts of “sink-or-swim” English-only lessons makes it difficult for them to understand academic instruction in English. Bilingual and dual language settings allow these students to begin learning English while deepening their abilities in their primary language, giving them opportunities to learn from classroom materials in both languages.

When voters lifted the bilingual education ban in 2016, California’s political leaders embraced the change. Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown and State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson set ambitious new goals through their “Global California 2030” initiative, pledging to have at least half of all California students enrolled in bilingual schools by 2030. And yet, in the ensuing nine years, the state has made only halting progress towards building a K–12 school system that aligns with that research-backed bilingual vision.

Ironically, when it comes to bilingual education, this deep blue coastal state could learn a lot from a conservative rival to the south. Texas enrolls roughly the same number of English learners in its K–12 schools, but serves them very differently. Indeed, for more than 50 years, the state has required school districts with significant numbers of English learners to offer them bilingual education. In 2019, it deepened its commitment to multilingualism, overhauling its school funding formula to make it in school districts’ interest to shift their programming to align with the research on how English learners learn best.

Like most states, Texas provides districts with a weighted funding boost to pay for language instruction for their English learner students. But the 2019 bill expands that boost for every English learner that districts enroll in the “gold standard” of bilingual education: dual language immersion programs. These bilingual schools teach in two languages, sometimes to integrated classrooms of English-learner and English-dominant students.

Critically, the bill also provided funding bonuses for non-English learner students enrolled in dual language programs. This gives districts a fiscal incentive to commit to the model even after English learner students reach English proficiency and are reclassified as non-English learners. In addition, it sets out an incentive for Texas districts to create integrated dual language immersion programs that enroll equal shares of native English speakers and native speakers of the program’s other language — usually Spanish.

Texas’ systemic bilingual investments have produced a very different English learner education landscape. Texas enrolls nearly 40% of its English learners in some form of bilingual education — twice the rate California does.

Given the research consensus on the efficacy of bilingual and dual language programming for English learners, it’s perhaps unsurprising that this gap is producing real differences in student achievement. These students in Texas outperform their English learner counterparts in California on a number of metrics. For instance, in Texas they have consistently scored higher than California English learners in both math and reading in every administration of the National Assessment for Educational Progress since 2011. Finally, achievement gaps between native English speakers and English learners are consistently smaller in the Lone Star State than in California.

States’ English learner policies are more important than ever now, as the Trump administration guts the federal Office of English Language Acquisition, which oversees hundreds of millions of dollars in federal funding earmarked for supporting those 5 million English learners. With funding cuts looming, potentially including the Elementary and Secondary Education Act’s Title III grants to support English learners’ language acquisition, states are likely to determine on their own the depth and breadth of their investment in the success of these students.

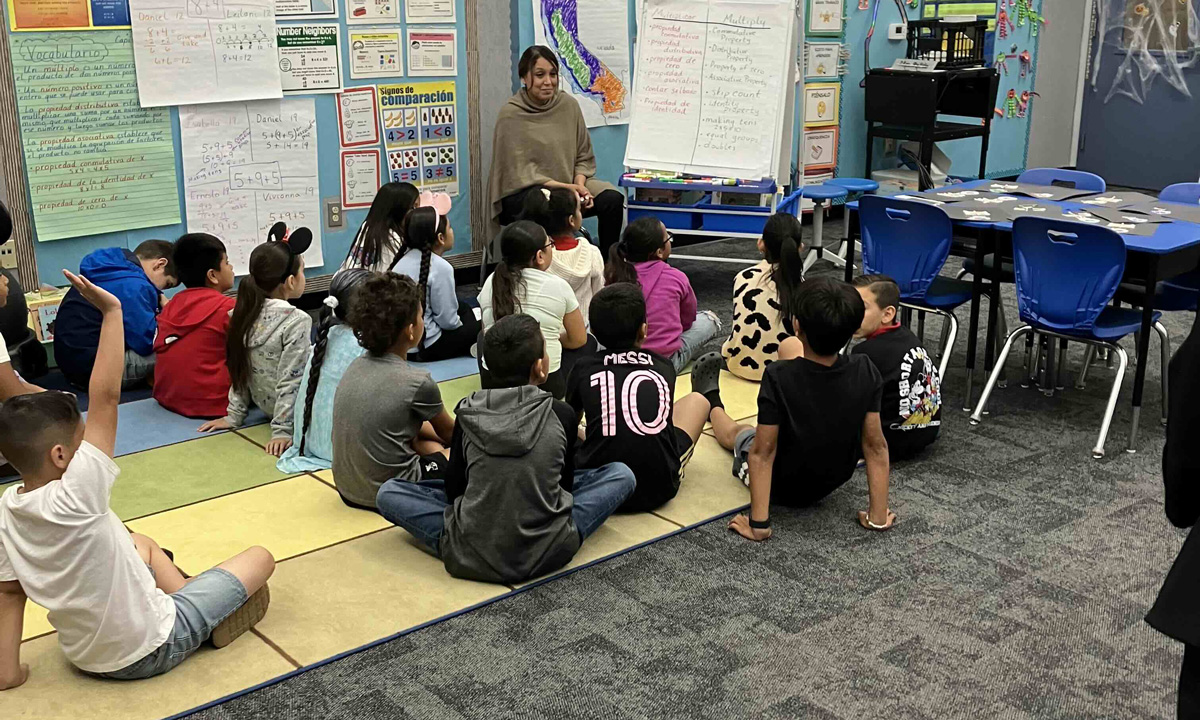

In California, local efforts like Delhi’s continue to push the state out of its failed English-only past. Delhi relaunched dual language immersion programs about a decade ago. Back then, the district “inherited a system that was not designed for all students to flourish,” Kubes said. So when he became superintendent in 2022, he moved to deepen Delhi’s commitment to those growing programs.

District leaders conducted public discussions in Spanish and English to learn what families wanted — and to help families of English learners learn about the value of developing their children’s home languages.

“What we offer,” said Gena Buchanan, principal at Delhi’s El Capitan Elementary, “is based on the needs of the community. It’s tailored to them. We used to have dual language immersion at just one site, but parents at the other schools started advocating for it, too.”

The shift is driving major changes for Delhi families. Over 50% of the district’s nearly 900 English learners are now enrolled in dual language. And long-time residents say that it’s reaffirming the value of their Spanish abilities.

“It’s personal for me because I went to school here,” said Rosa Gonzalez, principal at Delhi’s Harmony Elementary and a former Delhi student during the state’s English-only era. She said that she put her own daughters in the district’s bilingual programs because of her experience losing her native fluency in Spanish.

“I was struggling, as an adult, to communicate in Spanish,” she said, “even though that’s the language I had learned first when I was a kid. It was heartbreaking for me now to have to try to figure out how to speak to my grandparents, and I didn’t want my kids to have to go through that.”

But while local reforms like Delhi’s prove that California schools absolutely can deliver the language education models that research suggests work best, these efforts are definitionally limited in scope. In the near decade since relaunching bilingual education, California hasn’t made significant statewide policy changes to require districts to provide their communities with greater access to bilingual or dual language classrooms, nor has it provided substantial new resources to make it easier for districts to do so. State leaders have offered small competitive grant programs to seed several dozen new dual language programs, but have largely stopped touting the bilingual goals outlined in Global California 2030.

While dual language immersion programs are uniquely beneficial for English-learning students, they can help all children become bilingual. Delhi parent Rosa Nuno brought her children to the United States when they were in kindergarten and fifth grade. She was eager for them to learn English, she said, but was also determined to maintain their connections to their native language and culture.

“The more languages they learn, the better,” she said in Spanish. “And I want them to feel proud of their roots.”

Meanwhile, Buchanan, the principal at El Capitan, is starting her own bilingual journey.

“I’m English-only,” she said, “but seeing the benefits of dual language, I’m telling my children to enroll my grandchildren in our program. I’m an incredible supporter of it now. All the parents at my school know that I’m trying to learn Spanish.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)