New Report: How Districts Can Protect Fair Access to Dual Language Programs

In many big urban districts, the share of white students in popular dual language programs is rising while the share of English learners is shrinking

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Between the pandemic’s global health crisis, heightened culture wars and sharp political polarization, it’s been a particularly difficult few years for U.S. public schools. School board meetings host arguments over how — and whether — to narrow schools’ curricula. It’s hard to find consensus about what makes a great 21st-century school.

And yet, in most American cities — and a wide range of red, blue and purple communities across the country — a quiet consensus has formed around dual language immersion programs. These bilingual schools appear to appeal to everyone — for the past two decades, their numbers have rapidly increased. They’re popular because they offer 1) all students the chance to become bilingual in diverse learning settings, and 2) English learners the best chance to retain their emerging bilingual skills and succeed academically. But in a joint Century Foundation and the Children’s Equity Project report published this week, we show that these bonuses aren’t a certainty.

First: What are they? The most effective are “two-way” dual language immersion programs. These offer bilingual instruction and a bilingual social world — by enrolling roughly equal shares of children who are native speakers of English and children who are native speakers of the program’s other, “partner,” language. This is a major improvement on traditional U.S. language courses, where one Spanish-speaking (or French-speaking, or Arabic-speaking, etc.) teacher tries to cajole a classful of native English-speakers into conjugating verbs. It is also an improvement on traditional U.S. bilingual education programs, which usually only offer bilingual instruction long enough to transition English-learning children to English-only instruction.

But, as one of us noted in a 2017 article — and the New York Times’s hit podcast Nice White Parents flagged in 2020 — the relative scarcity of dual language schools means that these goals are in tension. One in 10 American students is an English learner and these students gain unique benefits from dual language programs, particularly when they’re integrated. And yet, in some cases, high demand for dual language from privileged, English-dominant, and often white families displaces less-privileged ELs, who are disproportionately likely to be children of color, have immigrant parents and come from low-income families.

It’s an elemental question of fairness: research suggests that policymakers should prioritize equitable dual language access for English-learning children, but also that diverse, linguistically integrated programs work best for ELs and English-dominant children alike. And, of course, the program’s popularity with the privileged can make it difficult to find a balance.

To get a clearer view of the situation, our new report analyzes more than 1,600 dual language schools enrolling more than 1 million students across 13 states and the District of Columbia. It explores the different ways that cities and school districts are navigating that tension in their dual language programs.

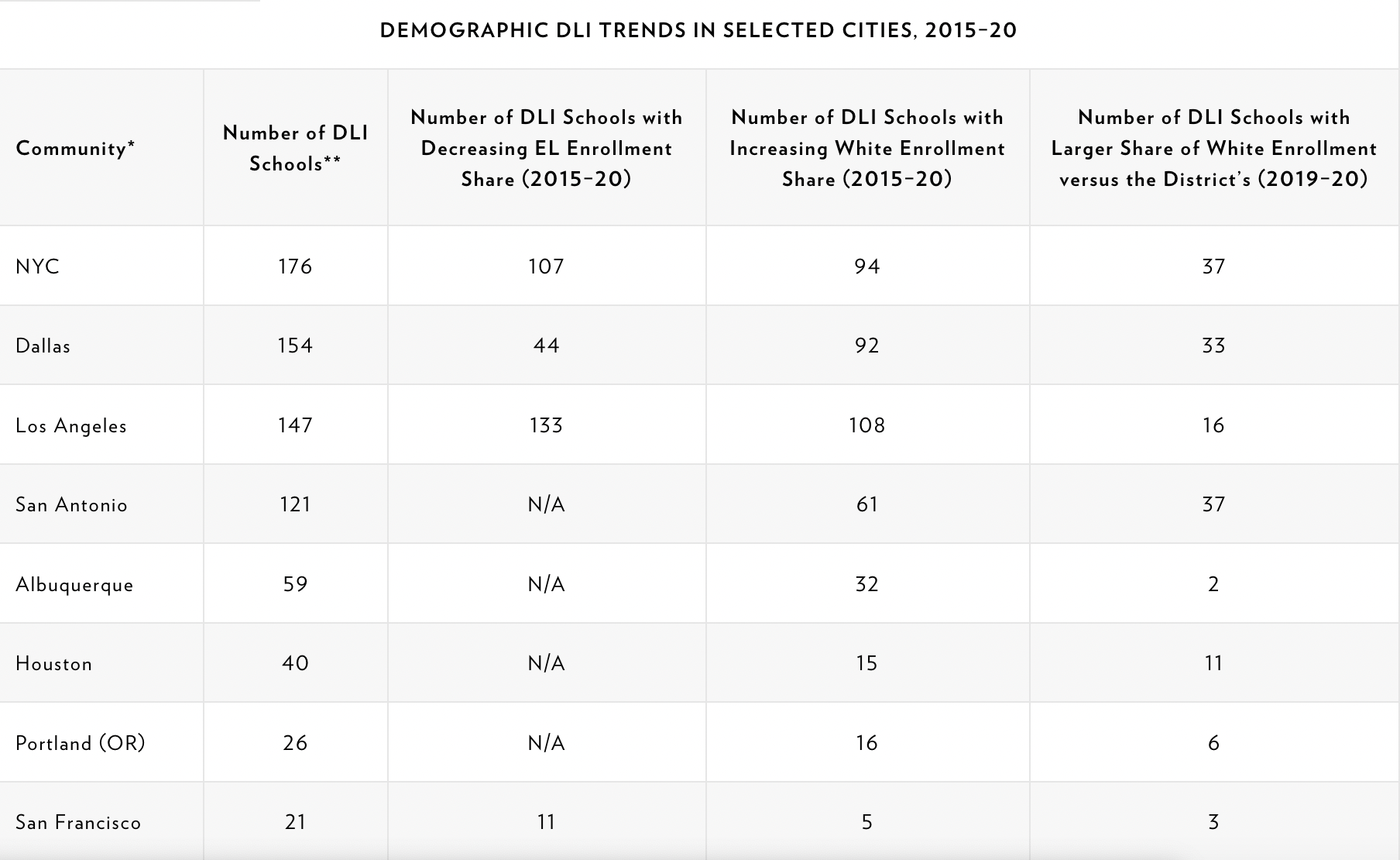

Given the tension between prioritizing English learners’ access and maintaining diverse dual-language campuses, it can be difficult to define and measure what counts as fair access. For instance, we found that a majority of dual-language schools in Dallas, New York City, Los Angeles, Albuquerque, Oakland, San Francisco, Houston, and Portland enrolled a lower share of white students compared to their share of the district population in 2020.

But we also found that access to these schools is changing over time. ELs’ share of dual-language enrollment shrank between 2015 and 2020 in a majority of these schools in New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, and San José. Meanwhile, white enrollment shares grew in a majority of dual-language schools in New York City, Dallas, Los Angeles, Albuquerque, Portland, and Washington, D.C.

These patterns are particularly striking in the context of shifting American public school demographics, where the share of white students has been shrinking — and the share of English learners has been growing.

Up to a point, enrolling more English-dominant students (of any race or ethnicity) can make dual-language schools work better for all students — including ELs. Indeed, while 92 of Dallas’s 154 dual-language programs got whiter since 2015, just 33 were whiter than the district in 2020. This is mostly because Dallas enrolls relatively few white, English-dominant students. A majority of the district’s students are current or former English learners and most come from Spanish-dominant homes. As a result, most of Dallas’s programs are “one-way” dual-language models, serving classrooms of only Spanish-dominant children. The upshot: the district might benefit from finding ways to increase English-dominant enrollment in these schools. Notably, San Antonio is pursuing this strategy in some of its dual-language programs.

The challenge, however, is to ensure that privileged, English-dominant families don’t fully colonize these schools and push ELs out. Fortunately, there are relatively straightforward ways for policymakers to protect English learners’ access. For instance, in rapidly gentrifying Washington, D.C., 13 out of 17 dual-language schools had student populations whiter than the district in 2020. But in San Francisco, another gentrification epicenter, just 3 out of 21 dual language schools were whiter than the district.

Demand for dual language is high in both places. Thousands of children wind up on D.C. dual language schools’ waitlists each year. In San Francisco, in one program, there were two applicants for each seat reserved for native Japanese-speakers and 15 applicants for each seat available to non-native Japanese speakers — and similar patterns in other dual language programs.

Notably, district leaders in San Francisco are much more aggressive about reserving seats for native speakers of the non-English partner language (e.g. Spanish, Cantonese, Mandarin, Japanese, Korean, etc.). The data suggest the reserved seats are perhaps the key difference — without them, demand from San Francisco’s English-dominant families would rapidly shift programs away from English learners who are native speakers of the program’s non-English languages. Our research suggests that more schools should consider similar policies to ensure that ELs have fair access to the dual-language classrooms that serve them best.

Finally, as we note in the report, “nothing exacerbates educational unfairness like scarcity.” The tension between prioritizing English learners’ access and enrolling diverse dual language classrooms would dissolve if there were enough programs to meet family demand. Local, state and federal policymakers should increase public investments in growing these programs. Above all, this means committing resources to train and license more of the bilingual teachers necessary to expand dual language instruction.

Without reforms like these, the country’s growing number of dual language programs could fall well short of their potential for ELs and English-dominant students alike. Dual language schools full of privileged, English-dominant children will be less effective at producing bilingual graduates. Dual language schools that segregate Spanish-dominant (or Arabic-dominant, Vietnamese-dominant, etc.) English learners away from their English-dominant peers risk reinforcing social separation between families of different backgrounds. Given the popularity and effectiveness of dual language programs with children from linguistically, racially, socioeconomically, ethnically and politically diverse communities, that would be a failure indeed.

Century Foundation senior fellow and 74 contributor Dr. Conor P. Williams; Children’s Equity Project executive director Dr. Shantel Meek; Century Foundation fellow Dr. Maggie Marcus and Century Foundation senior policy associate Jonathan Zabala are the co-authors of “Ensuring Equitable Access to Dual-Language Immersion Programs.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)