Teachers Leaving Jobs During Pandemic Find ‘Fertile’ Ground in New School Models

Microschools and online programs are attracting educators who valued the flexibility they gained during remote learning

By Linda Jacobson | June 12, 2022School closures in Vermont didn’t drag on as long as those in other parts of the country, but that didn’t lessen the strain.

Social distancing, masks and confining students to their classrooms caused an “explosive amount of mental health needs,” from lack of focus to outright aggression, said Heather Long, a former counselor in the Orange East Supervisory Union district.

“I started to watch as more and more restrictions were being placed on kids,” she said. “I felt like I couldn’t reach the needs.”

That feeling of helplessness is one reason Long left her job in December — joining others who’ve stepped away from traditional schools and transitioned to alternative education models during the pandemic. Now she’s running a microschool out of her New Hampshire home as part of Prenda, a network of tuition-free, small-group programs in six states. Teachers making the leap into such programs are finding parents willing to join them.

“For the first time in their lives, they have options,” said Jennifer Carolan, a former teacher in the Chicago area and now a partner with Reach Capital. The investment firm supports online programs and ed tech ventures, such as Outschool, with thousands of online classes, and Paper, a tutoring platform that states and districts have adopted using federal relief funds.

Traditional schools, Carolan said, haven’t kept pace with what teachers want in the workplace, particularly flexible schedules. And after a “hellish two years,” some are gravitating toward positions that personalize learning for students while offering a better work-life balance.

Prior to the pandemic, schools lost about 16% of their teachers each year, according to federal data. This year, multiple surveys point to scores of burned-out teachers who say they are planning to leave the field and anecdotal reports of mid-year departures. Rand Corp. data from last year showed that long hours, child care responsibilities and COVID-related health concerns were the main factors.

Traditionally, about two-thirds of teachers leaving the classroom have moved into other jobs in K-12. Staying at home to care for a child or other family member is the second most common reason. But since the pandemic, many are also finding private sector positions — often related to education.

With no hard national data yet available on teacher departures this year, experts say there’s no evidence of a mass exodus.

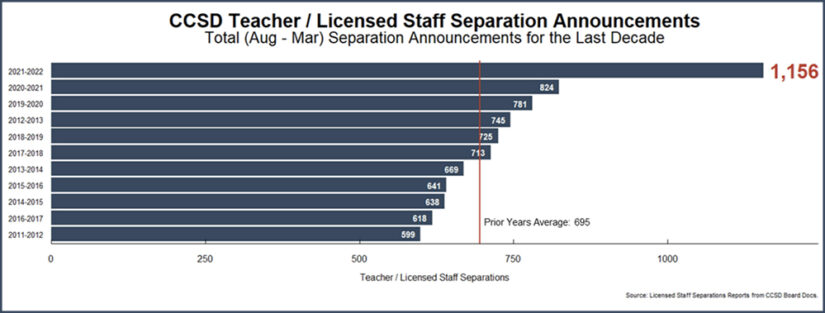

But there are signs in some states and districts that predictions of increased turnover are well-grounded. In Massachusetts, for example, turnover rates were 17% higher in the fall of 2021 than in 2020, and in the Clark County School District in Las Vegas, “separation announcements” of teachers and other licensed staff are well above pre-pandemic levels.

The question is whether microschools and similar models will continue to be a viable alternative for those leaving district schools. Chad Alderman, a policy director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University who follows trends in the teacher workforce, is skeptical they are sustainable.

“If even a few kids age out or move or just opt for a different placement, that would put the microschool at risk,” he said. “Absent some sort of consistent funding stream, they would face economic pressure to either grow into a more traditional school or else cease operations.”

Data last year from Tyton Partners, a consulting organization, showed that many families who left districts for pods and microschools were sticking with the model. At the start of the pandemic, some experts warned that pods and microschools would only worsen inequalities, drawing well-off families who could afford the cost. States such as Arizona and New Hampshire have since provided public funding to increase equity. And some networks focus on diversity, such as SchoolHouse — a platform that matches families with microschool teachers and attracted $8 million from investors last year.

‘A second shot’

Some teachers searching for new options have applied for jobs with Sora Schools, a private, online program now in its third year and serving 150 students, mostly on the East Coast. The school’s founders plan to expand in the fall of 2023 and eventually add in-person sites.

“The ground is fertile,” said Garrett Smiley, the company’s co-founder.

Several of the school’s teachers — called “experts” — joined the program during the pandemic and he gets a few hundred applications for each open position. The application of Angela Anskis, who learned about Sora on LinkedIn last summer, stood out.

She was teaching in a Philadelphia charter school, Boys Latin, when she began weighing a move. The school — and other public schools where she worked — didn’t offer students the choice to study what interested them, she said. After the school reopened, she found herself writing the same lesson plans for history, civics and geography that she always had.

“Once you’re teaching the same thing over and over and over again it’s hard to be passionate,” she said. “I would dread going into school. I thought that was part of being an adult.”

Anskis always wanted to be a teacher. As a kindergartner, she drew pictures of her future classroom. But returning to school after remote learning, she felt boxed in and considered leaving education completely. Sora, she said, gave her a “second shot.”

Sora educators are allowed to either focus full time on curriculum design or work directly with students — one difference that attracts teachers tired of spending nights and weekends on lesson plans, Smiley said. Experts teach six-week “expeditions” — deep dives into topics in multiple subject areas.

A humanities expert, Anskis has taught a unit on fashion history and blended English and current events into an expedition on banned books. Class discussions focused on “And Tango Makes Three,” about two male penguins raising a chick, and “Maus,” a graphic novel on the Holocast that was recently removed from classrooms in a Tennessee district. Students researched why some groups might be opposed to the books and read the banned titles with their parents’ permission.

Class sizes are small — 10 to 12 students — and Anskis said she can take a walk when she wants.

“I have so much more control over my life,” she said.

But not every teacher who has left the classroom during the pandemic set out to pursue new opportunities. Some felt pushed out.

Shatera Weaver was the dean of culture at Metropolitan Expeditionary Learning School, a New York City public school in Queens, where worked as an adviser for middle and high school students.

Originally granted an exemption from the city’s vaccine mandate because she has sickle cell anemia, Weaver learned in October that her accommodation would not be renewed. She was among the 1,400 New York City employees put on leave without pay because they were unvaccinated.

Now she’s designing curriculum for EL Education, a nonprofit that provides English language arts materials and teacher training. She also teaches yoga for a nonprofit, and strangely finds herself leading movement classes for young children in a public school.

“I have been quite unhappy. I miss my purpose-fulfilling job, and feel guilt for leaving — though it was out of my control,” she said. “I do not enjoy working from home. I miss the in-person connection and collaboration.”

Weaver hopes to join those who have launched new schools and wants to design either a public or private program for Black students — “much like an HBCU, but the grade school version.”

Teachers in alternative models said they appreciate the freedom to bring their own interests and personality to instruction. Long, in New Hampshire, took her six students — including her own two children — on a ski trip during the winter. Her program includes outdoor excursions for science and nature writing.

“I feel passionate about the ability to try new things and not be shot down,” she said.

This fall, she’s joining a former middle school science teacher to expand the program to 15 children. And she refers other teachers to informational sessions on Prenda, which the state supports through grants to school districts.

“I don’t want to turn families away,” she said, “and I don’t want to be the Prenda monopoly in town.”

Join The 74 and VELA Education Fund for a virtual conversation about why teachers leave the classroom to launch nontraditional education programs Wednesday, June 15, at 1 p.m. ET. Sign up here.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides funding to the 74 and the VELA Education Fund, which has supported Prenda.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter