Teachers Join Forces to Understand Dyscalculia, a Math-Related Learning Disorder

With little research or consensus on the topic — unlike its reading counterpart, dyslexia — educators are striving to identify and help kids with it.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A fifth grader who can’t read an analog clock or make change.

A 13-year-old who can’t tell if $20 million is greater than $200,000.

A first grader who doesn’t recognize that the numeral 5 is greater than the numeral 3 if the 3 appears larger in size on their paper.

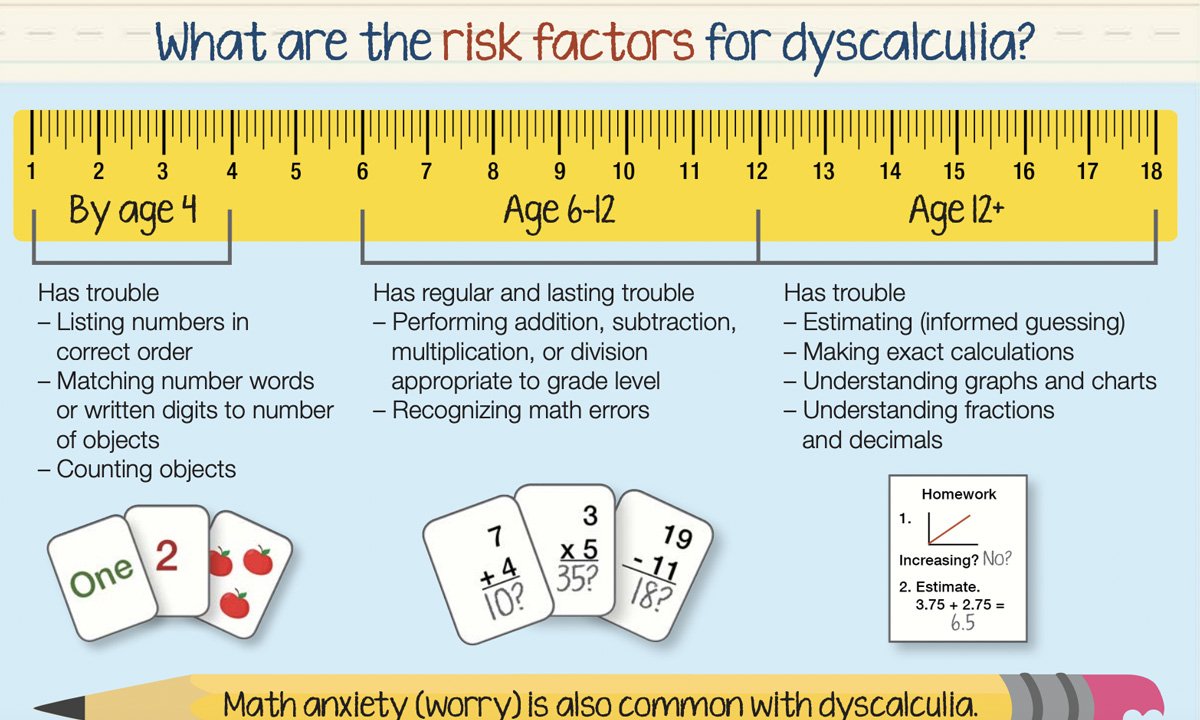

These are among the hallmarks of dyscalculia (pronounced dis-kal-KYOO-lee-uh), a learning disorder that hinders students’ ability in math, as they were observed in the classroom by long-time teachers.

But educators who saw these types of limitations in their students through the years told The 74 they didn’t always know what they were seeing — or how to mitigate it.

Toronto teacher Mufrida Nolan attributed some students’ difficulty with mathematics to a lack of confidence or foundational knowledge gaps. But some showed persistent problems, she said, including difficulty understanding place value — despite multiple explanations — or trouble memorizing basic math facts.

“To support these students, I relied on general strategies like breaking concepts into smaller steps, using visual aids and providing extra practice,” she said. “These interventions were helpful to a degree, but they lacked the specificity needed to address the unique challenges of dyscalculia, which I didn’t understand at the time.”

Just as dyslexia disrupts areas of the brain related to reading, dyscalculia affects the areas of the brain used to understand mathematics. Roughly 4% to 7% of students suffer from the condition, according to the Learning Disabilities Association of America.

Research indicates a link between the two: Children diagnosed with dyslexia are more likely to also have dyscalculia than those without a dyslexia diagnosis.

Teachers say, too, that dyslexia, which affects 20% of the population, is far better understood, leaving them mostly on their own in combating the math disorder that’s evidenced by difficulties with number sense and calculation.

Most of the educators who talked to The 74 said they first heard about dyscalculia in the early 2000s or 2010s, but said it didn’t start gaining traction until roughly three years ago, around the same time that teachers, policymakers and academic experts began to re-evaluate math instruction for all students in the face of COVID-era learning loss.

Nolan and other educators from the United States and Canada have been meeting online since September in a group called “Overthink Tank” to share the latest research and best practices on this lesser-known disorder.

Maureen Stewart, a seven-year Math for America Master Teacher — the nonprofit MfA was founded in 2004 to help retain and nurture outstanding New York City math educators — is grateful for the outlet. But, she said, identifying children as having the disorder is only the first step in helping them.

“The label is really not as important as the strategy,” said Stewart, who works in Brooklyn and has 17 years of teaching experience. “We have to be aware as educators, what am I seeing in this child and what does it really mean? It’s not like a checklist, and if you have everything on this checklist, you therefore have this thing.”

Mathematician John Mighton, the founder of the curriculum JUMP Math, said research in cognitive science suggests the teaching methods that work best for students with dyscalculia also work best for almost all other students. This includes scaffolding concepts into manageable chunks and providing lots of opportunity for practice.

But, he said, he agrees with teachers who say students with dyscalculia sometimes need something extra, adding it varies from one child to the next.

“Most of the students I’ve taught who had dyscalculia just needed to go back to very basic foundational concepts and learn them properly,” he said. “Then they can surprise you in how quickly they progress. Because teachers usually don’t have time to do this work, some think that the missing thing is invariably difficult to find or remediate.”

Mighton said, too, that teachers should introduce concepts with generic or semi-abstract models and representations rather than those that are overly detailed or contextualized, meaning they should steer away from complex word problems and present materials more plainly. He added that the sequence of problems should become incrementally harder.

Of course, dyscalculia is not the only challenge schools face in bolstering student achievement in math. Years of falling test scores have made K-12 learners’ lack of proficiency a full-scale emergency: It could threaten the nation’s global standing as the world moves even more toward technology-focused jobs.

Dawn Pagliaro-Newman, also an MƒA Master Teacher in Brooklyn, learned of dyscalculia through her daughter, Olivia, a fifth grader who loves to cook and who hopes to one day work for NASA.

Olivia attends a state-approved private school for students with learning disabilities where she said her teachers have equipped her with special tools to address dyscalculia.

“It’s like you need certain things to help you get through math,” Olivia said, adding it often takes her extra time to finish assignments. “If there is a test on division, that will take me hours. It’s hard for me.”

Dawn Frank, who also teaches in Toronto, said children with dyscalculia have no flexibility with numbers. Most learners, when they come to understand that 5+5 = 10, will also realize that 5+6 = 5+5 +1, Frank said.

Students with dyscalculia would not.

A sixth grader, when multiplying 21 x 30 would understand that 20 x 30 = 600 and another 30 is 630, she said. But students with dyscalculia would follow a standard set of rules, or algorithm, for solving the problem, “and in doing so would work much harder,” she said.

Some children also struggle with estimates. A second grader subtracts 4 from 20 and gets the answer 6 and does not see that this is not possible, Frank said.

“Anxiety is a common response,” she said. “Students, when they are anxious, will often avoid math. They might try to go to the bathroom a lot. There are students who miss school because their anxiety is so high or they purposefully have some kind of issue in the class before or in recess that causes them to miss math class.”

Children with dyscalculia, she said, also often have difficulty with time management and reading maps.

Further complicating matters, there is no consensus on how many types of dyscalculia there are: some experts say four, others more. And even when a child is diagnosed with the disorder, that doesn’t guarantee they will qualify for services.

The New York State education department notes, for example, that a clinical diagnosis of dyslexia, dysgraphia (a learning disability related to writing), or dyscalculia do not automatically qualify a student for special education programs and services — but that they are conditions that could qualify a student as having a learning disability.

Some families have tremendous difficulty in accessing the help their children need. Maryland-based attorney Nicole Joseph has represented some 800 students and their families in their fight for educational access in the past 20 years. Most suffer some combination of dyslexia, dysgraphia and dyscalculia, she said.

Part of the problem for children who struggle from math-related learning disabilities, Joseph said, is that teachers aren’t properly trained enough to help them — nor do they have sufficient time for the repetition and individual attention required.

While the science of reading has clarified the need for phonics-based instruction for all — and that this is particularly critical for children who, like Joseph’s son, have dyslexia — there is less clarity around mathematics.

Joseph said, too, that schools often fail to properly diagnose learning disabilities in well-behaved children, those who she called “bright, struggling and masking.” Part of her job is to help parents get a diagnosis — often through private psychologists — and to get schools to recognize their disability.

Despite these ongoing challenges, Pagliaro-Newman is hopeful about teachers’ growing understanding of the disorder.

“Because discussions of dyslexia, autism, and other neurodivergence have become more commonplace, I find that parents and educators are now turning their attention to math,” she said.

Increased awareness and the development of better strategies might help some children avoid later pitfalls. While they will struggle with the disorder for life — like dyslexia, dyscalculia doesn’t go away — some can still achieve great heights in the subject with workarounds, teachers in the Overthink Tank group told The 74.

“I am very excited about the conversations that are being had in the education community about how best to support these learners — as well as the questions being asked regarding much-needed research and funding,” Pagliaro-Newman said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)