Skeptical Supreme Court Asks: Do Race-Conscious Admissions Have an Endpoint?

But the Biden administration argued that removing race as a factor in admissions would have “destabilizing ramifications” across society

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The conservative-dominated U.S. Supreme Court seemed skeptical of whether universities should be able to continue the practice of considering race in admissions, and in arguments Monday, several justices openly questioned whether racial diversity offered any educational benefit.

If the tenor of the sometimes pointed exchanges are any indication, the outcome may hinge on how long universities expect to employ race-conscious admissions before such practices are no longer needed.

In arguments that lasted close to five hours, the court heard a pair of high-profile cases brought by a pro-Asian organization against Harvard and the University of North Carolina.

During the UNC case, which was heard first, attorneys representing the university argued that students are not admitted based on checking a racial box; rather, they look “holistically” at multiple factors, said Ryan Park, solicitor general of North Carolina, who insisted that race plays a “minimal” role in UNC’s decisions.

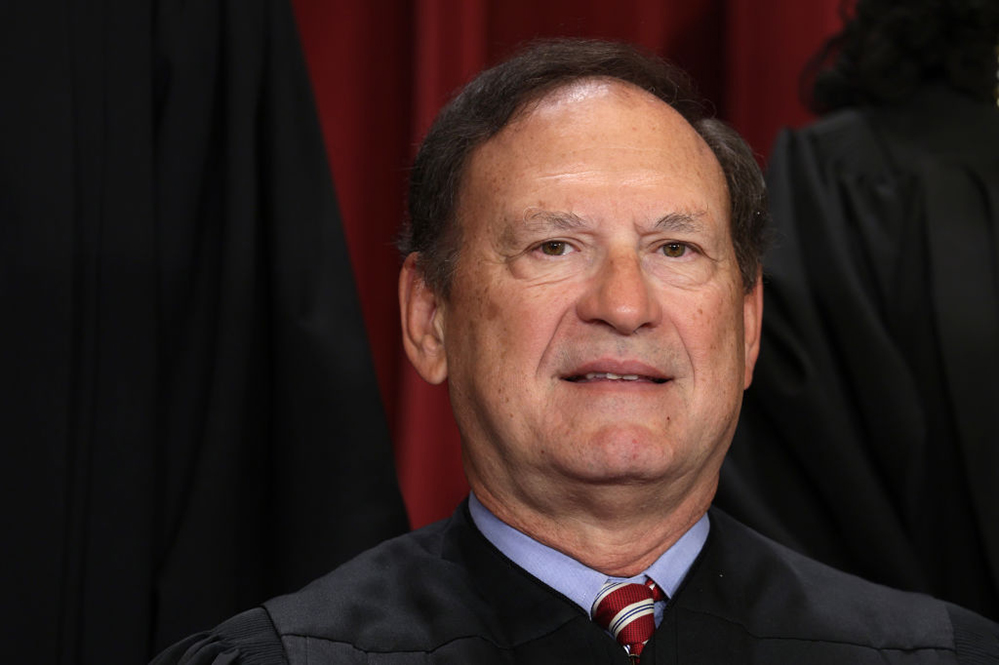

“If it’s irrelevant, then you shouldn’t care whether it’s ruled out,” Justice Samuel Alito said.

But Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who was only on the bench for the UNC arguments, repeatedly homed in on the notion that the universities only employed race as one criteria among many.

“The university is not requiring anybody to give their race. When you give your race, you’re not getting any special points. It’s being treated just on par with other factors in the system,” Jackson said. “No one’s automatically getting in.”

At a time when racial issues are at the forefront of educational debates and school politics, the historic cases reflect how polarizing attempts to address past discrimination have become. The court’s lengthy gauntlet Monday is also an indication of the far-reaching implications of its decisions in the two cases, which are expected in June.

Advocates for affirmative action argue it’s important for colleges and universities to consider race as one factor in their efforts to create a diverse student body, especially since K-12 schools remain segregated for Black and Hispanic students. But the plaintiffs, Students for Fair Admissions — with strong backing from Republicans and conservative organizations — say such policies are a form of illegal racial discrimination that put Asian students at a disadvantage.

The student group wants the court to overturn Grutter v. Bollinger, a 2003 ruling that upheld race-based admissions at the University of Michigan Law School. They argue that allowing such policies to continue violates Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which applies to any institution receiving federal funds, and the Constitution’s 14th Amendment, which applies to UNC as a public university.

“Grutter assumed that race would only be a plus. But race is a minus for Asians, a group that continues to face immense racial discrimination in this country,” said Cam Norris, representing the group in its lawsuit against Harvard. Asian students, he said, “should be getting into Harvard more than whites, but they don’t because Harvard gives them significantly lower personal ratings.”

He said that Harvard is not socioeconomically diverse and that removing race-conscious admissions would actually increase opportunities for Black students. But Seth Waxman, representing Harvard, disagreed with Norris’s statement that 80% of students at the university come from wealthier families. The university, he said, has increased financial aid as a way to reduce its reliance on racial preferences.

In the Harvard arguments, the conservative justices focused on a preliminary “personal rating” the university’s 40 admissions counselors apply to applicants as a form of “triage” to help sift through over 60,000 applications for just 1,600 spots at the elite university. Waxman showed the justices a chart that he said proves the role of race was so small, it was almost zero.

“So there is only a little racial discrimination,” Chief Justice John Roberts quipped.

In the Grutter decision, former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor suggested that 25 years in the future — 2028 — the use of racial preferences would no longer be necessary. The conservative justices repeatedly pressed the Harvard and UNC attorneys to give an “endpoint.”

Representing the Biden administration, Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar said the “arc of progress” has been slower than O’Connor envisioned and that universities should be diligent in using alternatives to race in their admission decisions.

Reacting to Monday’s arguments, Joshua Dunn, a political science professor at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, called the responses to the justices’ questions on this issue disappointing.

The lack of an endpoint “will allow the conservatives to say that schools have no intention of ever ending it, in violation of Grutter,” he said.

Both Waxman for Harvard and Park for UNC said that race-neutral alternatives have been insufficient in creating a diverse student body. Removing the option to consider race would reduce the percentage of Black students admitted to Harvard from 14% to 10%, Waxman said.

The justices — even conservatives Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett — raised the possibility of using race only in the context of a student’s life experiences.

“What if an applicant wrote an essay about how integral their racial identity was to them as a source of pride and the cultural attributes of their racial heritage were very important?” Barrett asked. “Would that be OK?”

But Thomas expressed some skepticism that diversity offered a value in and of itself. “I’ve heard the word diversity quite a few times, and I don’t have a clue what it means,” he said.

‘The bigger question’

This line of questioning suggests the court might not be as quick to end all racial preferences in admissions as many assumed, said Art Coleman, managing partner of EducationCounsel, a consulting firm.

“There is a majority of the court that is uncomfortable at some level with the notion of the consideration of race in admissions,” he said. “But I think the bigger question is what they do about that.”

While some observers have questioned whether the court would ultimately end even race-neutral, voluntary integration programs in K-12, Coleman said he doesn’t see the justices leaning that way. Instead, the legal question for the court is whether a student gets some “material benefit,” like admission or a scholarship, because of their race. That, he said, could have implications for “college counselors who are guiding students to and through the admissions process.”

The liberal justices pushed attorneys for the plaintiffs to explain whether eliminating racial preferences in college admissions would result in a lack of racial diversity across society as a whole. Prelogar, representing the U.S. government, said during the UNC hearing that it is “critically important” to have diversity in the military, and then added during the Harvard arguments that removing race-conscious measures would have “destabilizing ramifications in just about every important industry in America.”

The two hearings offered a history lesson on the nation’s unfinished work to redress its racist past. Speaking on behalf of UNC, David Hinojosa, director of the Educational Opportunities Project at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights, said Black students can be discouraged from applying to the university when they see Confederate statues on campus or witness demonstrations by white supremacy groups.

The plaintiffs argued that the court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, ending desegregation in K-12, should have applied to race-conscious admissions in college. That prompted a strong response from Prelogar.

“There is a world of difference between the situation this court confronted in Brown, the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine that was designed to exclude African Americans based on notions of racial inferiority,” she said. The court recognized, she said, that such discrimination affected children’s “hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)