Senators Tell Schools Chiefs They Plan to Act on School Safety With More Money for Counselors, Better Security, No Mention of Guns

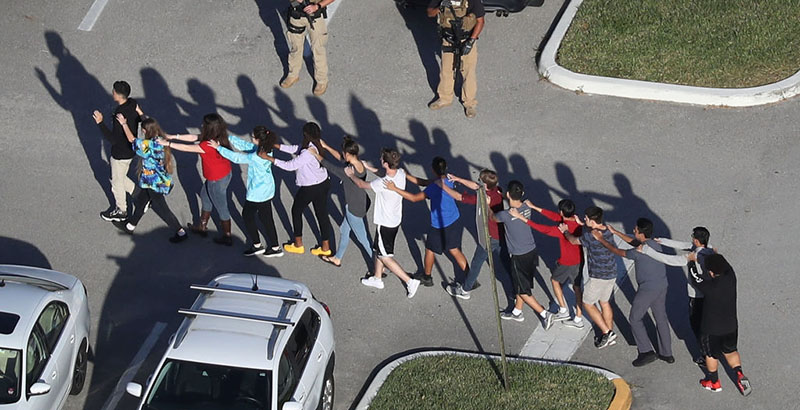

Though much of the attention in the wake of the Parkland, Florida, school shooting has been focused on President Donald Trump’s controversial calls to arm teachers and end gun-free school zones, smaller, less contentious efforts to improve school safety are taking shape in Congress.

Those measures, congressional leaders said this week, will focus largely on federal grants for mental health programs and school safety.

Sen. Lamar Alexander told a meeting of the Council of Chief State School Officers Tuesday morning that he’ll introduce a bill that would expand the allowable use of existing federal funds for more school counselors, violence prevention and mental health programs, plus infrastructure upgrades like alarms or security systems.

House Republican Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, meanwhile, announced Tuesday that his chamber would vote next week on a bill to reauthorize a grant program given through the Justice Department that helps districts purchase metal detectors, locks, and other security upgrades for schools. A similar bill has been introduced in the Senate; each has backers from both parties.

Alexander’s bill would allow new uses of grants under ESSA’s Title II, which pays for teacher training and salaries, to hire and fund professional development for school counselors, and Title IV, a catchall provision for other school services, to pay for infrastructure upgrades. Grants under both titles could be used for violence prevention and anti-bullying programs.

Besides broadening the allowable uses of existing dollars — Title II is currently funded at about $2 billion, and Title IV at $400 million — Congress might authorize additional funding, Alexander said.

“There might be additional money under Title II and Title IV under the areas I described, but at least we can start by broadening the authority,” he added, without specifying how much more might be expected.

The Trump administration has proposed eliminating Title II funding, an idea House Republicans approved in their fiscal 2018 Education Department funding bill. Senators kept the funding in their initial draft. Lawmakers have yet to write a full funding bill for fiscal 2018, which is close to halfway over, though they agreed to raise caps on overall spending for the next two years, which should make doing so easier.

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos — whose budget proposal, released before the Parkland shooting, proposed cutting school safety grants — said Monday she would back calls for more federal dollars if needed.

“Where there is a need for more resources at the federal level, we will certainly be advocating for those, in support of the state and local communities,” she told education reporters Monday after meeting with state education chiefs. CCSSO has started a school safety working group.

Alexander, too, was clear that his long-standing belief that K-12 education is a state and local responsibility applies to school safety, too.

“I wish there were some edict that I or someone in Washington could issue and suddenly make 100,000 public schools safer, but that’s not true,” he said.

Gun control advocates would argue there are measures the federal government could take, such as universal background checks or banning semi-automatic weapons like the one used in the Florida shooting. Those issues, though, would be outside of Alexander’s purview on the Education Committee.

A bipartisan measure to require universal background checks failed to pass the Senate after the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting that left 20 children and six adult staff members dead. The smaller-scale proposals discussed in Congress are unlikely to satisfy the Parkland students who have become the faces of gun control advocacy, or their peers who are planning national rallies and walkouts, including one on March 14.

Alexander’s bill would also reauthorize an expired public health law that allows an arm of the Department of Health and Human Services to help state and local communities create a plan to support children struggling with violence. Newtown used the program successfully to help students after the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary, he said.

Kentucky Commissioner Stephen Pruitt — whose state was the site of a high school shooting in January — urged Alexander to think about what happens after a shooting.

“My eyes were opened to [the aftermath], you also have to pay attention to what happens after,” he said.

Vermont Education Secretary Rebecca Holcombe, while praising an emphasis on tending to students’ needs after such tragedies, said Alexander and his colleagues also shouldn’t lose focus on preventing attacks.

“I worry that we are going to be complacent and just accept that we have to just respond after they happen, rather than doing the work we need to do up front to make it less likely to happen in the first place,” she said, without specifying what that would be.

Alexander’s bill also would create an inter-agency task force with representatives from several federal agencies to make recommendations, but not mandates, on school safety.

He plans to introduce the bill this week, staff said.

Other lawmakers encouraged looking into the broader issue of school discipline and law enforcement on campus.

Rep. Bobby Scott, the ranking Democrat on the House Education and the Workforce Committee, urged state officials to “use measured and deliberate initiatives and base your policies on evidence and research, not on slogans and sound bites.”

An increase in police officers in recent years hasn’t quelled violence and has led to more arrests for minor behavioral infractions, pushing more students into the school-to-prison pipeline, he told CCSSO officials Tuesday.

Sen. Marco Rubio, Republican of Florida, meanwhile, wrote to DeVos and Attorney General Jeff Sessions Monday asking them to revise 2014 guidance that encouraged districts to report students to police less often. The guidance “may have contributed to a systemic failure” to report the alleged gunman to law enforcement, he said in the letter.

The alleged shooter was ultimately expelled from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School for “disciplinary reasons.” He was the subject of “dozens” of 911 calls, calls to children’s services, and at least two tips to the FBI, NPR reported. FBI officials will be on Capitol Hill next week to face lawmakers’ questions about their lack of response to those warnings.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)