Desperate to Advance a Cure for a Deadly Virus, U.S. Schools Played Critical Role In 1950s Polio Vaccine Trials

By Harry McCracken | April 6, 2021

When the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorized the use of Pfizer and Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccines last December — a year after the coronavirus was first identified in Wuhan, China — it was a dramatic piece of good news after one of the most disruptive years the country has ever experienced.

Now consider the thrill people felt in April 1955 when Dr. Jonas Salk’s new polio vaccine was officially declared to be “safe, effective, and potent.” That came more than 60 years after the first known polio outbreak in the U.S., which took place in rural Rutland County, Vermont in 1894. It killed 18 — mostly children below the age of 12 – and left 123 permanently paralyzed.

From there, polio became an enduring, mysterious scourge. In 1916, it hit New York City, killing 2,343 out of a total of 6,000 nationwide that year. In the 1940s and early 1950s, the number of incidents in the U.S. grew eightfold, reaching 37 per 100,000 population by 1952. The fact that children were most susceptible to the disease made it only more terrifying.

The Salk vaccine was approved only after going through the largest clinical trial in history. Rather than being a government project, this test was overseen and paid for by a nonprofit organization founded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1938: The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, better known as the March of Dimes. (Roosevelt himself had contracted polio at the unusually advanced age of 39.) More than 1.3 million children participated; some got either the vaccine, which required three shots over a five-week period, or a placebo, while others underwent observation for polio.

The only logical way to reach so many children was through schools. The result was an unprecedented national effort built atop public-education infrastructure. In the spring of 1954, school boards, principals, teachers, school nurses, and even PTAs all joined the cause, along with volunteers such as “classroom mothers.”

Of course, schools had long played a role in the U.S. health system, including administering vaccines for illnesses such as smallpox and diphtheria. But nothing prepared them for the polio trial, which involved not a vaccine already known to be safe and effective but one still in the process of being validated. David M. Oshinsky, author of Polio: An American Story, quoted the March of Dimes’s Melvin Glasser as saying that the organization concluded that the undertaking required the cooperation of 14,000 principals and 50,000 teachers.

This highly coordinated undertaking was a wildly successful, critical step in the war against polio. Today, with news that a study has shown Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine to be 100 percent effective for kids 12 to 15 — and evidence that a meaningful minority of parents are still hesitant about allowing their children to be vaccinated — it’s worth revisiting what went so right 67 years ago.

For the March of Dimes and others involved in launching the polio vaccine trial, step one was securing the approval of the local officials who oversaw the schools whose students would take part. Such educators tended to see participation as an act of patriotism as much as a medical experiment. In pledging its support, for instance, Lincoln, Nebraska’s Board of Education and school administration called the trial “a unique educational opportunity” and declared that it would “bring to our children not only greater understanding of the nation’s fight against this disease, but will add to their sense of personal pride and accomplishment. In this respect, it can be a very real factor in the development of good citizenship.”

In Akron, Ohio, the school board voted 6-0 to proceed as part of the trial. The Akron Beacon Journal reported that only one board member, Willard Seiberling, expressed any caution — and that was over the fact that some students would receive a placebo: “Why can’t all the youngsters get the real thing instead of half getting worthless salt water?”

The next task — securing permission from parents for their children to take part in the trial — was equally important and far more fraught. Here too, existing educational infrastructure was essential. Local PTAs held meetings at which school nurses and other medical professionals explained the vaccine and testing process to parents, sometimes with the aid of movies or film strips.

Along with these official materials and meetings, newspapers were filled with what we’d now call FAQs. How many shots would a child get? Haven’t there been some medical experts who have said that this vaccine isn’t ready for testing? Should parents have their child tested for polio immunity before allowing them to volunteer for the program? In answering these questions, the goal was to knock down fears and myths that might stand in the way of the trial.

As April arrived, schools sent consent forms home with students for their parents to sign. They didn’t have much time to think it over. In Pittsburgh, the forms were distributed on a Monday and were to be returned by the following Wednesday, allowing for two nights of consideration. As Oshinsky notes, the form had parents “request” that their child participate in the trial rather than “give permission”— a meaningful word choice intended to make it sound like an honor that should be sought.

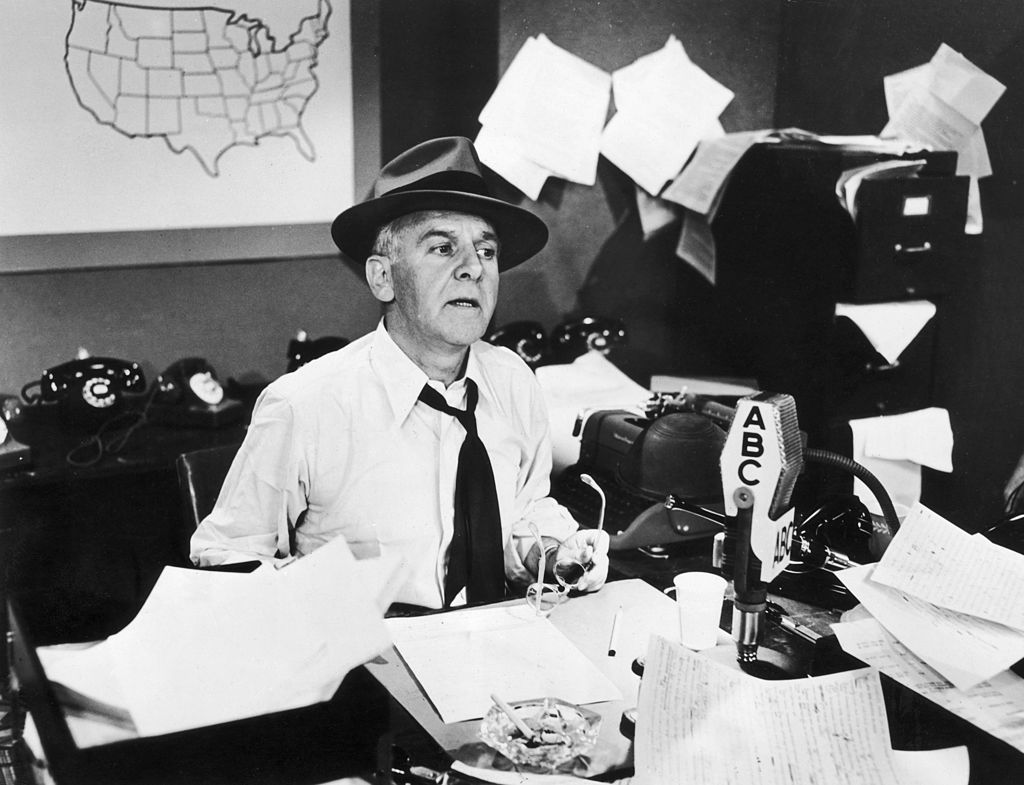

Despite the exhilaration over the possibility that an end to polio might be imminent, the nation was jittery. And on April 4, Walter Winchell sent some people into outright panic. On his Sunday night radio show, the famed columnist and broadcaster questioned the safety of the trial, saying that the vaccine had killed monkeys in tests and “may be a killer.”

Winchell spoke just as schools were distributing consent forms, and spooked many parents. As a result, one estimate said, 150,000 children dropped out of the trial. Health experts quickly defended the safety of the vaccine; Jonas Salk himself accused Winchell of playing “armchair scientist” and “sidewalk superintendent.” The pushback may have helped calm nerves: A week after Winchell’s broadcast, Utah’s Ogden Standard-Examiner reported that most of the parents who had withdrawn their permission then reinstated it.

Even without Winchell’s last-minute disruption, the effort to convince parents to sign the consent forms would have been only partially successful. An American Journal of Public Health report on the trial surveyed mothers whose children were enrolled in five schools in a single Virginia county. Of 175 mothers surveyed, 42 percent declined to grant permission for their kids to participate in the trial. More than 80 percent of those who refused said that they harbored doubts about the vaccine’s safety.

Nonetheless, the trial went on. On April 26, 1954, at Franklin Sherman Elementary School’s gymnasium in McLean, Virginia, a meaningful moment in the history of public health occurred when 6-year-old Randall Kerr became the first person to get injected with Salk’s vaccine as part of the trial — not by happenstance, his second-grade teacher emphasized, but because he was eager to be at the front of the line. Randall expressed concern that the vaccine could somehow bring back his poison ivy. But once Dr. Richard Mulvaney stuck the needle in his arm, he said it hurt less than his penicillin shot had. He was rewarded with a lollipop, and that was that.

A photograph documenting the event appeared on the front pages of newspapers across the country. In the weeks to come, the photos of additional schoolchildren kept coming: Mark Knudsen of Salt Lake City, Gerry Midkiff of Oklahoma City, Nancy McIntyre of Kansas City, Missouri, Gary Caudle and Sandra Smith of Rochester New York, and countless others.

Sometimes, these students were depicted calmly getting shots at school. Once they had gone through the entire three-shot process, they were often shown smiling and brandishing “Polio Pioneer” pins and certificates, making their role in the trial official. It was an achievement many of them would never forget.

By the end of the school year, the process of injecting students with the vaccine or placebo was complete and analysis of the resulting data began. That was a painstaking process, and the doctor who supervised the trial, Thomas Francis of the University of Michigan, didn’t rush his work.

While local medical officials awaited the results, they began making provisional plans for a massive vaccine program, again relying on school systems as the primary means of distribution. As one local paper explained, “If [the vaccine] is licensed by the Govt — and national health officials seem certain it will be — the three shots will immediately be offered to all first and second graders in the U.S., Alaska, and Hawaii.”

On April 12, 1955, Francis told the world that the trial had been a success. The news was received with excitement, joy, and relief — and schools across the country got to work, including ones in areas that hadn’t participated in the trial. For instance, The Morning Call of Allentown Pennsylvania reported that 92 percent of local first- and second-graders had been signed up for free inoculations, which began on April 27.

One more development kept the vaccine at the top of the news — and it was a tragic one. As children were being vaccinated at schools, doctors found that some of them who’d received their shots went on to contract polio anyhow, then spread it to family members and neighbors. After these cases were traced to vaccines produced by Cutter Laboratories of Berkeley, California, an investigation revealed that the company had accidentally released doses containing dangerous live viruses. Tens of thousands of people were sickened, 200 were paralyzed, and 10 died. Most were schoolchildren.

The so-called “Cutter incident” briefly halted the vaccine program and shook parents’ confidence. But then it started up again, regained the public’s trust, and went on. Over the next few years, thanks to the Salk vaccine, incidents of polio were dramatically reduced, falling to fewer than 100 in 1960.

After decades of front-page stories about polio, culminating in the drama of the Salk vaccine’s development, testing, and distribution, the disease largely left headlines. Instead, it showed up mostly in brief items such as this 1958 announcement in a Minnesota paper:

The last Salk polio vaccine of the school year will be Wednesday at the St. Joseph school in St. Joseph. Time is 9 a.m.

School children and pre-school children needing first, second, or third shots are invited to attend. Any youngster who had his second polio inoculation seven months ago can receive his third and final shot at this time,

St. John the Baptist school children also have been invited to this clinic. A local physician will administer the shot.

That polio was no longer a major topic of news was a triumph for humanity. The trial played an enormous role in making that possible. The students who took part may have gotten the Polio Pioneer pins, but heroes throughout the U.S. education system made it all possible — and their heavy lifting should be remembered and cherished.

Likewise, the current rollout of the Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccines is a triumph of medical science. Unlike polio, COVID-19 has mostly spared children, so they weren’t initially prioritized in the trials. But now that the Pfizer vaccine has been shown to be remarkably effective on older children, and with Dr. Fauci predicting that younger children will be eligible early next year, once again, millions of kids will line up for shots — echoing the moment in the 1950s that made such a difference.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter