Schools Have Lost $16B in Capital Funds Since the Great Recession. Those Buildings Are in Trouble — & That Means Problems for Students

The aging school buildings of Arizona’s Glendale Elementary School District were no match for the late summer monsoons of 2016. With foundations made brittle after years of prolonged water damage, flooding seeped in. A structural engineer feared that walls would give way.

School leaders scrambled to find new spaces for nearly 1,500 students until outside contractors could remediate waterlogged walls and floors and reinforce foundations in two buildings. Some students were shuttled to another school in the district; others were sent to a neighboring town.

Superintendent Cindy Segotta-Jones didn’t want to make the students relocate. But with aging buildings desperately needing repair after years of underfunding, she had no choice. “You can’t tell me that it doesn’t impact their learning when they’re in a different environment,” she said. “These disruptions are not fair to children.”

America’s schools, many built in the late 1960s and early 1970s, are due for a major overhaul after decades of inadequate funding made worse by the 2008 recession. These old buildings are only getting older — in Glendale, where some schools date to the 1940s, drainage problems make them vulnerable during the rainy season and aging air conditioners frequently conk out as temperatures soar to 115 degrees.

Infrastructure needs are so intense, particularly in rural and urban areas without strong local tax bases that can compensate for the lack of state funding, that advocates describe the situation as a national crisis. “There’s a storm coming, and everybody knows it,” said Danny Adelman, executive director of the Arizona Center for Law in the Public Interest, which is suing the state on behalf of several districts, including Glendale, for more capital funding.

After the recession in 2008, states made major cuts in all areas, including school spending. In Arizona, school officials estimate that the state has slashed capital funding by $2 billion since 2009. Yet as the economy has improved and states have reinvigorated their budgets, spending on school construction has not bounced back, according to a recent report and analysis from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington, D.C., think tank that analyzes federal and state government budget policies.

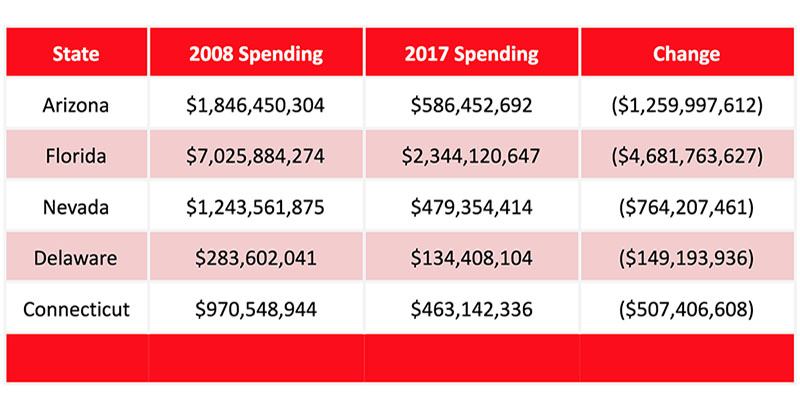

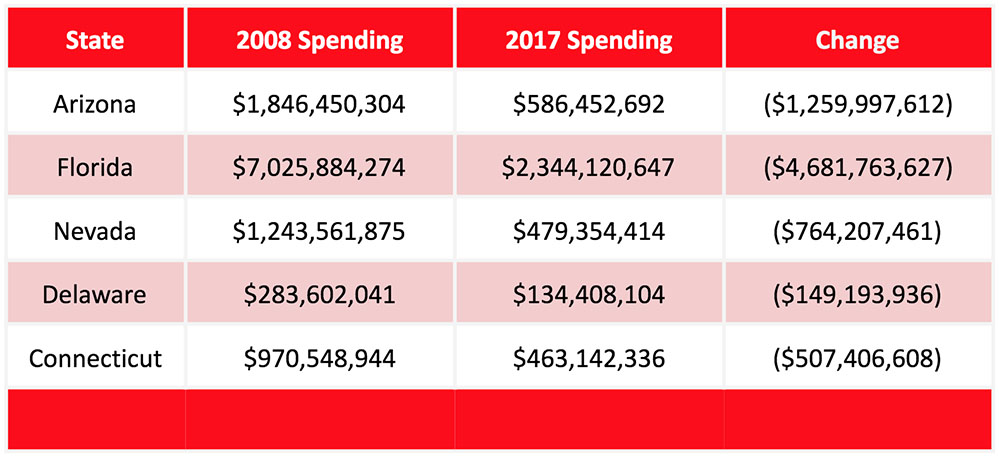

Drawing on census data on state and local capital spending, the center’s senior director, Michael Leachman, said expenditures for schools nationwide declined 20 percent between 2008 and 2017 — the equivalent of a $16 billion cut, when adjusted for inflation.

He said the cuts were especially severe in five states. Schools in Connecticut lost 52 percent of their capital funding between 2008 and 2017, when adjusted for inflation; Delaware lost 53 percent; and Nevada lost 61 percent. Schools in Florida and Arizona, which he called the two hardest-hit states, lost 67 and 68 percent, respectively.

With an estimated $145 billion per year needed for maintenance, repairs and new construction, American public schools are facing a $46 billion budget gap, according to a 2016 report from the 21st Century School Fund, the National Council on School Facilities and the U.S. Green Building Council.

Nearly 50 million kids and 6 million teachers and other adults visit public school buildings every school day, according to a June 2017 report from the Center for Green Schools. “Every day,” the report says, “millions of children in the U.S. attend public school in unhealthy, unsafe, educationally inadequate, environmentally unsustainable, and financially inefficient facilities.”

More than half of the public schools in the country needed to spend money on repairs, renovations and modernization to put them in good overall condition, according to a 2014 report from the National Center for Education Statistics. Problems range from leaky roofs to faulty heating and ventilation systems to antiquated plumbing, lighting, electrical and communications systems.

Research shows that academic achievement is linked to building conditions. Harvard researchers last year found that poorly cooled classrooms have a significant impact on student learning. Yet the connection between the ability to learn — particularly for low-income students — and the condition of the learning environment is sometimes lost on the public. Liz Beardsley, senior counsel for the U.S Green Building Council, said recent research showed that only 39 percent of Americans see the connection between buildings and green spaces and their own well-being.

A dire need, from coast to coast

In Philadelphia, the teachers union estimated in March that it would cost $170 million for asbestos abatement and to remedy other health risks. Then, at the beginning of this school year, 1,000 students at Benjamin Franklin High School and Leadership Academy were relocated to two other schools, as their school was closed indefinitely for asbestos removal.

This past August, teachers in Baltimore asked the community to donate fans to cool their classrooms — but district leaders feared that the electrical load would tax the schools’ aging wiring. Then, in September, 50 district schools sent students home early because they lacked air-conditioning as temperatures reached the upper 90s. This in a city where, two winters ago, students had to wear coats and blankets in class for weeks because there was no heat. The Baltimore Sun reported that the city’s schools, which educate 85,000 students, have a $3 billion maintenance backlog from decades of underfunding.

In Hawaii, 20 percent of the school buildings are more than 100 years old; the average age is 61. Besides not having enough air conditioners in classrooms, the state’s public schools, which educate 185,000 students, need $7 billion to catch up on overdue repairs and maintenance and create new classrooms in overcrowded areas, the Hawaii Department of Education estimated. With current capital funding from the state, Honolulu Civil Beat reported, it will take 23 years to complete all those high-priority jobs.

In Florida, one-third of the school buildings in Duval County, which includes Jacksonville and surrounding areas, are in poor or very poor condition, the Florida Times-Union reported. Maintaining or replacing the district’s 159 school buildings, which serve 129,000 students, will cost more than $1 billion; whereas the district received $103 million a year from the state for capital needs a decade ago, it now gets $22 million. In Palm Beach County, meanwhile, students have had to work in the hallways because their classrooms were too hot. The Palm Beach Post wrote that “district administrators admit to skimping on repairs and replacements when tax revenue fell during and after the Great Recession, setting the stage for many of today’s problems.”

In Boston, classrooms are freezing cold during the winter, conditions “you would never see … in a modern office place,” said Phoebe Beierle, a manager at the Center for Green Schools. In Richmond, Virginia, students and teachers must contend with vermin, mold, leaky roofs, falling ceiling tiles, windows that don’t open and restrooms that don’t have stall doors.

Problems may be even greater than these reports in the local press, said Mary Filardo, executive director of the 21st Century School Fund, since superintendents are often hesitant to expose their districts’ problems to the public.

“When the average age of a building is 44 years, things start to fail,” she said.

In addition to emergencies like lead and asbestos abatement, deferred maintenance and repairs of everything from plumbing to roofs, many buildings need ramps and elevators installed to comply with the Americans With Disabilities Act. Then there’s retrofitting to conform to modern security recommendations set in place after Sandy Hook and other school shootings, said Jeff Vincent, director of the Center for Cities and Schools at the University of California, Berkeley. This includes installing classroom doors that lock from the inside, better security cameras and single points of entry into school buildings.

Even basic security measures, such as a functioning intercom system, are a challenge in some districts, like Glendale. “I need to be able to communicate to all staff at all times. And I can’t necessarily do that when my intercom systems aren’t working,” Segotta-Jones said.

Schools also use capital budgets for improving outdoor spaces, like playgrounds, parking lots and retaining walls, as well as for purchasing computers and textbooks. Because of funding shortfalls, some of the science and government textbooks in Glendale’s classrooms are more than 10 years old, Segotta-Jones said. Teachers try to compensate by getting creative — giving students online materials to supplement out-of-date textbooks and working with Verizon to provide iPads in several schools. But these solutions are often temporary.

A desert case study

After the 2008 recession, the Arizona state legislature turned off the two major funding streams for school capital expenditures, Adelman said. As a result, he estimated, local school districts have lost more than $5.5 billion from the state. “Some districts lost 80 to 90 percent of their state funding for school facilities and other capital items like technology, school buses and textbooks,” he said. Arizona’s schools, which educate 1.1 million students, now must rely almost entirely on local tax bonds to maintain their buildings and buy new equipment. But many districts cannot support bond measures.

While Arizona’s economy has bounced back, state legislators chose to give taxpayers a rebate this year rather than spend money on schools, said David Lujan, director of The Arizona Center for Economic Progress. “Republicans are reducing revenues to the point that we have a very limited state government,” he said. “When you’ve gone this long with underfunding, it has a real impact on learning and academic success.”

To pressure to the state to restore capital funding, Adelman is representing four school districts, the Arizona School Board Association, the Arizona Education Association, Arizona School Administrators and a local taxpayer in a lawsuit, Glendale Elementary School District v. the State of Arizona. They say the current system, which relies on asking local taxpayers to cover school capital expenses, creates inequities because districts with expensive homes and larger commercial zones can raise more funds than districts without those resources. Low-property-wealth school districts have fewer computers, older air conditioners and less-safe buildings than richer areas — an unconstitutional, unequal system, Adelman said. Although the state has added more funds for schools — $80 million in this budget year for building repairs and upgrades, up from $26.7 million in 2015 — this is insufficient to meet the needs in the state, according to Adelman and the plaintiffs in his case.

“It creates huge disparities,” he said. “When you can’t pass local bonds and overrides, you are left behind.”

For example, the Laveen Elementary School District, near Glendale, has lost about $20 million in state funding over 10 years, but Superintendent Bill Johnson raised $69 million through local tax bonds to build four new school buildings to accommodate a booming population. “These cuts were devastating for many school districts in Arizona. We were able to get through those times through voter-approved and -funded bonds, but most school districts really felt that hit,” Johnson said.

In contrast, the Glendale school district lost at least $38 million from the state but raised just $35 million from the local community last November for repairs, new facilities and security improvements. District leaders say they will need another $55 million over the next 10 years for everything from structural repairs to textbooks, which will be very difficult without help from the state.

To address inequities like these, Filardo said, the federal government should target more money to the highest-needs schools or incentivize state action. “Schools help our economy work. They are a really important part of the well-being of our overall country. Funding schools should be a federal, state and local responsibility,” she said.

“Public schools are the nation’s second-largest public infrastructure expenditure, beyond roads and highways,” Beierle said. “But the federal government only provides a fraction of funding for school buildings.”

Federal legislation for $100 billion in school infrastructure spending — the Rebuild America’s School Act — was first introduced in Congress in 2017 but has yet to come to a vote.

Although Leachman’s data show a slight increase in state and local spending nationwide since its low in 2014, many experts said change isn’t happening fast enough. New investment in school infrastructure is needed immediately to keep children safe and learning appropriately, Leachman said — and that urgency is what pushed the Glendale District to join the lawsuit that’s challenging the state.

“I think we owe that to our students,” Segotta-Jones said. “That’s our responsibility. They deserve to be in the best learning environment possible.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)