Looking for Mental Health Care and Falling Into an ‘Internet Wormhole’

By Marianna McMurdock | September 7, 2021

58% of young New Yorkers didn’t get the help they needed during the pandemic. Here’s what they faced

For five months during her freshman year, Tuli Hannan called New York City mental health providers in her mother’s insurance network after outreach to her school guidance counselor fell flat. In 2016, most therapists she contacted near her Queens home looked to put her on a six-month or longer wait list.

Hannan, who grappled with the will to live at that time, ultimately found a therapist she felt comfortable with at the end of her sophomore year, more than two years after she identified a need for support. Though her search began long before the traumas associated with COVID-19, large numbers of young New Yorkers are facing the same difficulty in accessing mental health support at a time when demand is intensifying.

“You don’t know where to narrow it down, you feel so lost,” Hannan said. “Being the person that’s struggling, you have to keep a stable mind and the patience to look for these services.”

The process led her to become an advocate for expanded mental health support in NYC, where a plethora of services — from community-based organizations, hotlines, in-school clinics and private professionals — left her spiraling and continues to confound her peers, who will return to classrooms next week.

A February 2021 survey of about 1,300 New York City youth, aged 14-24, found that only 42 percent who sought mental health support received it. Across the city, 35 percent of young people surveyed expressed a want or need for services; in the Bronx, half of youth surveyed wanted access.

“People my age, my friends, they normalize the fact that we won’t get the help that we need,” said Hannan, who worked with the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York on the “Voicing Our Future” survey while she was a student at Information Technology High School.

New York’s School Response Clinicians, a group of 85 social workers helping students in crisis to lessen 911 and emergency room outreach, supported 3,591 unique students from October through December 2020, up from 242 students from July through September.

The data from NYC mirror mental health stories across age groups nationally — from elementary schoolers withdrawing from class activities in Los Angeles to a 51 percent spike in emergency room visits among teen girls after suspected suicide attempts. That the pandemic is exacerbating a pre-existing youth mental health crisis is by now well documented.

At least 28 states have pledged to bolster social-emotional and mental health support with pandemic relief funding. Oklahoma, for instance, dedicated $35 million for a School Counselor Corps of licensed mental health professionals. And since 2020, seven more states now allow mental health days as excused absences from school.

To help support the 26 New York City neighborhoods most deeply affected by the pandemic, the city’s Department of Education partnered with NYC Health + Hospitals to establish more mental health clinics in schools.

The DOE has hired at least 500 more social workers as a part of its $635 million academic recovery plan. In the city’s 2022 budget, about $165 million has been earmarked for mental health recovery. No line items reference youth mental health specifically. This could be a red flag in an already-murky support area — many providers fit under the same umbrella of “mental health services,” though not all provide services to adolescents.

Jennifer March is executive director of Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York, the nonprofit advocacy group which specializes in research and conducted the February youth mental health survey. March has led campaigns to improve young New Yorkers’ well-being and is among those closely watching how pandemic stimulus funding will be allocated.

“While the recent New York City FY22 approved budget takes tremendous steps in New York’s recovery, the level of suffering and trauma the city’s children and families have experienced requires further action to address. The lack of specificity on how the city will ensure access to critical behavioral health supports and how public dollars will be spent to address long-standing racial disparities in access to child mental health care is deeply concerning,” March wrote in an email to The 74.

Looking for help and finding the internet wormhole

For students and families looking for mental health support, the first question becomes: Where do I start? In the internet age, they’re likely to find four sites in a quick search: the DOE’s school mental health page, the Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health site for accessing supports at home, the Department of Health’s hub for child and adolescent services and NYC Well, the confidential 24/7 text, chat and call hotline.

The sites link to each other frequently — the first section of the DOE’s page, for example, lists how to contact NYC Well for immediate assistance, and the Office of Community Mental Health site refers anyone looking to support a young person to the DOE. Yet the relationship between the agencies, and which mental health professional might exist at yours or your child’s school, are unclear without spending hours of research or calling a school directly.

The stigma and fear associated with reaching out for mental health support may prevent someone from turning to a school administrator. One Brooklyn student shared in the write-in portion of the mental health survey that they believe support outside of school should be made free to increase accessibility.

“I feel like people are afraid to talk to people in school in fear that someone will tell their parents what they say. Even if it’s just giving special access through an app like BetterHelp or offering phone calls for 30 minute sessions with therapists who will just let people vent about problems. I’m not sure who would organize that or even if this is already a thing. If it is, it should be better promoted.”

Through the end of July, individuals seeking help were likely to encounter at least some broken links, such as those on an education department Q&A page directing to a tool on how to start a conversation over mental health concerns with their child’s school, or one at the Mayor’s Office for Community Mental Health that offered resources for teens experiencing abuse. Now, both the DOE and mayor’s office resources have been fixed.

Given that each school’s need varies, mental health support systems range from community schools, which offer wraparound health services; to clinics, health centers, specialists and prevention/intervention programs.

For a parent urgently looking through the DOE’s site for the best person to call at their child’s school, the differences between these iterations and the linked sheet listing what program each school has, without contact information, is not exactly user friendly.

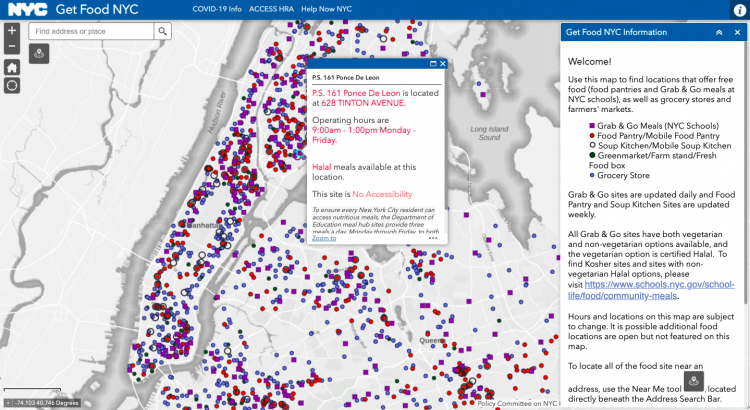

The city’s Office of Emergency Management operates an interactive map for free food resources. The 74 could not find a comparable online resource for mental health that lists drop-in youth centers, community-based mental health organizations, and/or school-based mental health services. The closest resource city-wide is ‘Hite,’ a health and social services directory, though it does not include school-based resources.

The Community Mental Health office does provide a map of programs on its data dashboard, but that platform is primarily meant to track reach and impact of city services. A parent or student seeking support cannot use it to find location sites, contact information or learn more. For some youth-specific services, map markers do not populate.

Some students or families opt for the NYC Well hotline to streamline understanding of their options and connect with care providers. Of the people who called on someone else’s behalf in 2019, nearly half called for their child. NYC Well’s average answering speed or wait time was 33 seconds from July 2020 through June 2021, according to the Office of Community Mental Health.

In the Citizens’ Committee survey, a number of youth acknowledged that accessing support could be easier if the process and resources were made transparent in school, where they spend so much of their day. Specifically, one Queens student recommended having therapists accessible in schools and dedicating days or weeks to mental health awareness and establishing healthy habits.

In-school mental health supports inconsistent

A number of schools adopted new mental health initiatives because of and during the pandemic to meet student needs. Now 19 and recently graduated, Tuli Hannan was able to see her school partner with a community-based organization to provide more mental health services.

Students at Information Technology High School in Queens can now access on-call therapists during the school day and take online courses related to mental health, including mindfulness, reflective writing and meditation. Having access to those resources when she searched in 2016 could have made all the difference, she said.

“Now it’s easier for us to reach out to our guidance counselors because they email us, letting us know that this is what’s out here, this is what’s accessible to you, and don’t be afraid to reach out to us,” Hannan said. “I wish that that was passed on to all public schools because I know it’s different at each school.”

The New York Foundling, a centuries-old institution providing care for families and children, is one of many community organizations operating in-school mental health services. Through satellite clinics and staffing school support teams, they assist a student population of about 4,000 at 11 K-12 schools in the Bronx, Manhattan and Queens.

The Foundling is also contracted to provide clinical support in school response teams, a mix of providers and school staff that address students in crisis — a group not tethered to a specific school location.

With an end-goal to break the stigma around mental health and sustain a young person’s well-being, they involve the whole school. In practice, that means year-round support is available for students, as are workshops, training or professional development with any of the adults a young person encounters: guidance counselors, teachers, school leadership and their own families.

“We don’t only focus on the students. We believe that in order for mental health services to be sustainable and effective in school, we have to address the entire school as our client, as a community that we’re working with,” said Reïna Batrony, vice president of services for community- and school-based programs.

To get the word out about their services and full-time clinical staff, Batrony’s teams show up. At PTA meetings, afterschool events or summer school launches, staff share contact information and talk about their work, with the added bonus of normalizing the topic of mental health with parents. Students can also self-refer to their services, they don’t require a staff person or parent to make the call.

“I think everyone tends to be hesitant about mental health support. [It] varies based on culture, based on the type of trauma they may have experienced,” Batrony said. “[It] may also vary based on prior providers they may have experienced.”

The Foundling doesn’t maintain a waitlist; at the schools they partner with, a full-time clinician responds to each referral and request, connecting students or families with their services or community-based resources. For therapy sessions, they meet with youth in a confidential school space, in their homes or at one of their borough offices.

Their services and approach to involving everyone in a young person’s orbit in their mental health could have been impactful for a student like Tuli Hannan, who struggled to find support outside of school. The Foundling partners with just a sliver of the DOE’s 1,866 schools and the decision about which ones get that level of support is made by its Office of School Health after assessing a school’s need for services, according to Batrony.

The result is inconsistent access to professional mental health support for students. For schools without full-time clinical staff or mental health centers, the baseline is a referral system and access to as-needed crisis response teams.

Guidance counselors, teachers and administrators receive training on how to refer or respond in a crisis — according to the DOE, over 75,000 school-based staff were trained in Trauma Responsive Educational Practices since last year — but are not qualified to provide counseling, psychotherapy or act as social workers.

Ife Damon has been teaching New Yorkers for seven years, and says she proactively addresses mental health in the classroom to help students handle emotions and become self-aware. Since the pandemic began, she’s witnessed her English students at Curtis High School express “feelings of anxiety, stress, even depression.”

Damon makes it known to her classes that there is an in-house mental health center, and if they’re interested, they can connect with her, a guidance counselor, social worker or with the center directly. Young people, she says, typically talk openly about their mental health only “when teachers provide opportunities for students to do so.”

Located on Staten Island’s north shore, Curtis High serves predominantly Black and Latino students, who make up about 77 percent of the student body, and is one of the city’s 267 community schools. Their school-based health center provides vision, medical, dental and mental health care, coordinated by community-based organizations.

Damon serves on the community school advisory board, which hosts an annual forum open to students, parents and community members to assess community need and potential expansion. The forums also solicit feedback for the model, as Damon explains, “How can we better support you as a parent? How can we collaborate with you as a stakeholder in order to strengthen our school and help to make sure our students are getting what they need?”

The RAND Corporation’s 2020 assessment of community schools found that the model boosted high school graduation rates, decreased chronic absenteeism and resulted in fewer disciplinary incidents for elementary and middle schoolers.

Community schools make up about 14 percent of NYC public schools. For students in the 267 schools, the model expands access to having many of their basic needs met; though citywide, 74 percent of students experience poverty. The DOE has plans to add 130 more community schools to support pandemic healing.

“We know that students cannot fully engage in learning unless their social-emotional and mental health needs are being met. Our expansion of successful programs in 2019 established a common approach to supporting students through teacher training, resources, and direct clinical help,” DOE deputy press secretary Nathaniel Styer told The 74 in an email.

The department’s growing investments in clinical partnerships are “to ensure every student has a caring adult to go to when in crisis.”

More money, a new mayor and a critical moment

While the push to expand affordable mental health support to New Yorkers has been ongoing, unprecedented federal stimulus money fosters a moment in which the city may turn its focus to youth and families.

Licensed master social worker Melissa Koppenhafer works with unhoused young people accessing mental health, housing and workforce support in CORE’s Lighthouse transitional living centers for 16- to 24-year-olds. She said that expanding school and community-based services is critical for the next mayor, but the cost must be subsidized to prevent further financial strain on young people. As CORE’s senior program director of youth and family services, Koppenhafer works with young people who are mostly covered by Medicaid or are uninsured.

“Programs that are available to them that accept Medicaid and are completely free, without a copay, are really going to be what’s successful,” she said. “Twenty dollars is a lot to them. If they’re working minimum wage, that’s more than their one-hour right there.”

In order to foster sustained mental health care for young people, Koppenhafer is also calling for the city to recruit and retain more mental health practitioners of color.

“As someone in the field, I find that people in general tend to like to have providers that they feel they can connect to via race, culture, history — any one of those things can help them connect to someone,” she said.

Though the DOE has hired hundreds of social workers for this school year, it’s unclear whether any efforts are being made to recruit social workers to better match a student population that is 40 percent Hispanic/Latino, 25 percent Black, 16 percent Asian and 15 percent white. Advocates say that while it’s a welcome expansion, meeting the recommended 250:1 ratio for students to social workers would require hiring more than 2,200.

Eric Adams, Brooklyn borough president, former city police captain and the Democratic mayoral candidate poised to win November’s general election, has said little on the specifics of expanding mental health support for young New Yorkers. On the campaign trail, he argued against removing any of the 5,300 police safety agents in schools.

Police interventions for students in emotional distress rose from 2016 to 2020, according to a recent analysis by Advocates for Children of New York. Looking into 12,000 incidents where children were transported to hospitals for psychological evaluations, data shows that Black students and students with disabilities were disproportionately affected and handcuffed.

An April 2021 youth survey found that NYC students vastly preferred more guidance and mental health support over police, and more than two-thirds of those surveyed agreed police should be removed completely.

Advocates contend that NYC’s particular context — on the eve of a mayoral shift, with families’ demand for accessible care mounting along with an influx of federal pandemic relief funds — positions city leaders to make lasting change for youth facing mental health challenges.

“There is a critical opportunity in the year ahead,” said the Citizens’ Committee’s Jennifer March, “to invest in place-based preventive and clinical interventions in pediatric settings, child care and pre-K, schools and communities as our children and adolescents are in crisis and their behavioral health needs have skyrocketed.”

Lead image: At I.S. 584 in the Bronx, sisters Melody and Delany received in-school mental health care from the New York Foundling. (Ryan Lash / New York Foundling)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter