Schneider: The Strange Case of ‘China’ and Its Top PISA Rankings — How Cherry-Picking Regions to Take Part Skews Its High Scores

The results of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), released by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), are always a big deal, since PISA assesses the reading, math and science literacy of 15-year-old students in almost 80 education systems from around the globe, including all 37 OECD countries. Most news stories, in the U.S. and elsewhere, focus on the average scores and the rankings of countries based on those scores.

There are always some surprises in the rankings — and countries gain a few minutes of fame for doing surprisingly well on PISA. This is often accompanied by a wave of education experts decamping to these high-scoring countries to find the secret sauce the U.S. could learn from. Finland has had its moment, as have Poland, Singapore and Vietnam, as destinations for well-meaning, globetrotting edu-tourists wanting to learn from the successes of these countries.

My bet for the next wave of edu-tourism, based on the 2018 PISA results released Dec. 3: Estonia, the highest-performing European nation. To be sure, Estonia is doing great things using data to improve its education system, and it obviously has found a formula that works for its students. Whether its approach to literacy can scale to different countries is an open question, and those interested in learning more should book their tickets to Estonia. But as they do so, I hope they avoid adding even higher-scoring China to their itinerary.

The temptation to look to China for lessons on effective education is built into the PISA rankings. “B-S-J-Z (China)” appears at the very top of all three — reading, math and science — often by a substantial margin. B-S-J-Z stand for Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang, the four mainland provinces that OECD allows China to “represent” it on PISA. This is in contrast to the norm of countrywide testing.

B-S-J-Z (China)’s performance is amazing; maybe too amazing. For example, B-S-J-Z (China) was 6 points ahead of consistent PISA powerhouse Singapore on reading. The gap in math between the four Chinese provinces and Singapore — again, the second-highest scorer — was 22 points; in science, 39 points. But before we anoint “China” as the world leader in education, and before we descend on China to learn how it does so well, keep in mind that there are many reasons to believe these high scores do not accurately reflect China’s education system.

We can begin with Tom Loveless’s excellent analysis of why Shanghai’s high scores from its first PISA participation in 2012 should be questioned. Loveless shows how the OECD secretariat allowed China to choose its richest province to participate, one in which many students cannot attend high schools because of the notorious hukou household registration system that restricts rural migrants’ access to urban social services, including education. Loveless further shows how the secretariat wanted China in the PISA program so badly that it allowed the selection of only China’s richest province into the program. This elevated OECD’s desire to be a global enterprise over preserving the integrity of the PISA enterprise itself. (Incidentally, OECD’s global ambition is also evident in its desire to include up to 40 more countries in PISA despite questions of the impact of the expansion on PISA.)

Letting a country select only a few provinces to test violates PISA’s own norms, and the biased results can distort global views of what works in education and undermine PISA’s very credibility. Unfortunately, OECD’s preference for global reach over high quality continues to this day, as is evident in China being allowed to continue cherry-picking the provinces included in PISA.

Here’s what U.S. PISA scores might look like if we could report a select subset of our country’s scores as representing the entire nation. In 2015, Massachusetts opted to administer PISA statewide. Not surprisingly, its students did extremely well. As the Massachusetts state department of education proclaimed on its website: “Massachusetts Students Score Among World Leaders on PISA Reading, Science and Math Tests: State’s Reading Scores at Same Level as World’s Top Nations.”

Now consider the affluent New York City suburb of Scarsdale. It, too, contracted with OECD for a special districtwide assessment. In 2017, its board reported that Scarsdale outperformed “the international competition.” While U.S. performance on PISA is at best mediocre, imagine if we substituted Massachusetts, Minnesota, Scarsdale and, say, Evanston, Illinois — we could call it “M-M-S-E (U.S.)” — for the entire country. We would be right up there with B-S-J-Z (China), Singapore and Estonia, with all attendant bragging rights.

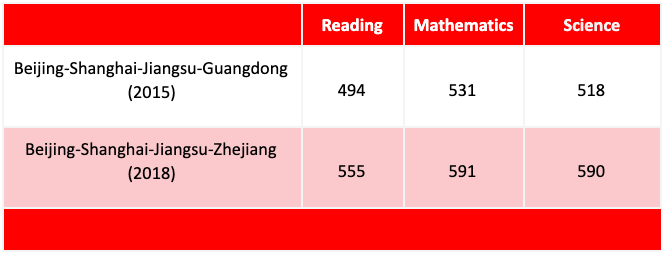

One final wrinkle: In 2015, China was represented by Beijing-Shanghai-Jiangsu-Guangdong. In 2018, Guangdong was replaced by Zhejiang. Substituting B-S-J-Z for B-S-J-G was consequential. Consider the following:

Average Scores

The point is clear: Allowing China to handpick a few of its richest provinces as representing the entire country distorts the very purpose of PISA as a comparative test of national education systems. These four Chinese provinces represent only 13 percent of the population. Further, because of the hukou system, school enrollment in these provinces likely represents even a smaller share of junior and secondary education enrollment in China (9 percent). It is possible that the substitution of one province for another was driven by legitimate reasons known to China and to the OECD secretariat, and that this 60-plus-point jump in PISA scores was purely an innocent coincidence. Detailed data on the individual provinces were not released in 2015, and detailed data from 2018 have not been shared with the U.S. or, as far as we know, other OECD countries.

The OECD secretariat claims to have doubts about how well China could create the nationwide sample of schools necessary to administer PISA. But China is now the world’s second-largest economy, and given the depth of its administrative state, that argument seems specious. The OECD secretariat needs to either expand testing nationwide to bring China in line with overall PISA standards or have China excluded as a PISA participant.

In the meantime, my advice to my edu-tourist friend: Enjoy your trip to Estonia. Stop in Finland and Poland for other lessons. And on your way back home, visit Scarsdale or Massachusetts with the money you save on the long flight to China.

Mark Schneider is director of the Institute of Education Sciences at the United States Department of Education. Before assuming that role, he was a vice president and Institute Fellow at the American Institutes for Research and the president of College Measures. He previously served as the U.S. commissioner of education statistics from 2005 to 2008 and is a distinguished professor emeritus of political science at the State University of New York, Stony Brook.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)