Mark Schneider: PISA Is a Unique Resource for Testing Educational Attainment of 15-Year-Olds in 78 Countries. Adding 40 More Would Be a Mistake

In a recent commentary in Ed Week, I discussed two emerging problems in PISA, the Program for International Student Assessment, administered by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. I identified OECD’s insufficient attention to research and development (driven in part by its pursuit of “innovative” topics) and the too-short three-year testing cycle (which is outdated by new assessment technologies). Here I want to focus on yet another emerging problem: OECD’s global ambitions for PISA.

OECD serves as a forum in which the governments of 36 advanced democracies with market-based economies plus the European Union work together to address common problems and identify best practices. Since 1961, it has been a source of market-friendly, evidence-based research and policy advice.

As OECD has has expanded its membership from its original 20 countries, the number of nations administering PISA has grown even faster, from 32 in the year 2000 to 78 last year (including some Chinese provinces and other subnational entities). With that growth, the composition of the countries participating in PISA has changed dramatically. Member nations represented almost 90 percent of PISA participants in 2000 but less than half in 2018. By 2030, OECD wants to add some 40 more countries to PISA, further diluting the representation of its members.

PISA is a unique international resource, so it is not surprising that many countries want to participate in the assessment, something encouraged by OECD’s secretariat. But the logistical challenge of the undertaking is already formidable. In 2018, PISA assessed nearly 1 million 15-year-olds across the globe, accommodating 131 languages in communities ranging from rural impoverished to urban affluent. Adding 40 more countries will amplify these challenges.

Although such growth may seem like it would strengthen PISA, it does just the opposite, by increasing the burden on the overall program, undermining the meaningfulness of comparative statistics based on the assessment, and limiting the potential of innovative digital assessment content.

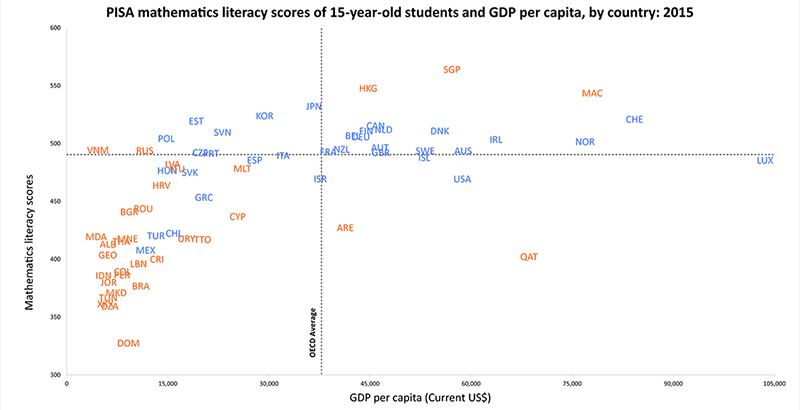

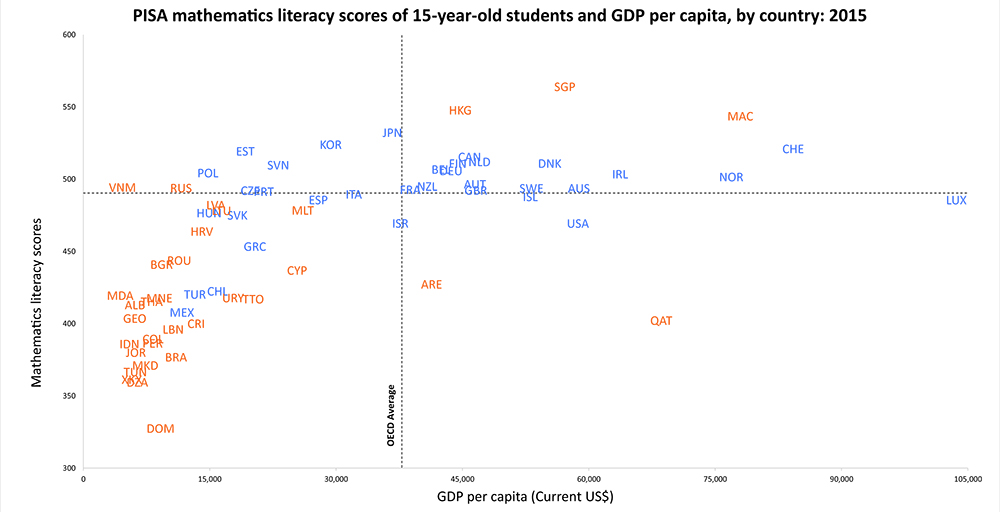

The burden on the program is not just logistics and linguistics; it is also the growing challenge of keeping PISA a one-size assessment for all. Overall, non-member countries represent wildly different levels of student achievement and equally wide differences in educational and societal conditions that exceed the differences found across member nations.

To be clear: It is technically possible to report PISA scores for all these countries on a common scale. Doing so, however, runs the risk of undermining the meaningfulness of a program that, at its core, seeks to provide sound policy advice based on comparable data. Even now, OECD admits that PISA’s measures of economic, social, and cultural status do not adequately capture the conditions found in low-income countries.

The tension between the need for comparable data and the growing heterogeneity of PISA countries becomes clear when considering out-of-school rates for the 15-year-olds PISA is designed to assess. In many non-member PISA countries, out-of-school rates are far higher than within member countries and many 15-year-olds are enrolled in grades below those that are eligible for PISA. In PISA 2015, about half the 15-year-olds in Vietnam and about one-third in Brazil, Costa Rica, and Beijing-Shanghai-Jiangsu-Guangdong, China, were excluded or not enrolled in school. Such differences call into question the validity of PISA’s comparisons of the skills of the 15-year-old population —a problem that will grow worse as OECD pursues its global ambition of having about 100 non-member countries take part.

To increase such participation, OECD has launched the PISA for Development (PISA-D) initiative to assess students in even more low-income, non-member countries. Currently, Cambodia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay, Senegal, and Zambia are included in PISA-D. However, 15-year-olds in many of these PISA-D countries perform even lower than students in the current pool of non-member countries. The lowest-performing country averages 258 on a 1,000-point scale — some 70 points lower than the lowest-performing current participant in the main PISA (the Dominican Republic), around 180 points less than the lowest-scoring member country, and more than 230 points lower than the member average.

Given the heterogeneity in student performance and social/economic conditions across nations, a single global assessment for even more countries is problematic. A great amount of time and resources have been invested so that PISA assessments can give an accurate picture of the skills of youth in the first set of developing countries to join PISA. However, such work becomes exponentially more complex and costly to do successfully as the range of skills continues to widen.

Technical issues also arise from the differential ability of countries to administer PISA. All member countries have made the transition from paper-based to digitally based testing, but the limited technical capacities of many non-member countries make it necessary to retain a paper-based version. This adds complexity to the testing and, as more and more low-income countries join PISA, the question of how paper- versus computer-based tests affects the performance of different populations becomes increasingly important and difficult to answer. The need to preserve comparability between computer- and paper-based testing also acts as a brake on developing creative ways to test old content, not to mention new content that can be tested only with a fully digitally based assessment.

The addition of so many non-member countries also creates problems with governance and finance. Decisions about PISA are made by the PISA Governing Board, which has several membership tiers. OECD members are automatically invited to participate on the board, and all currently do. Non-member countries can be associate members, with full voting rights. Right now, only Brazil and Thailand are associates, but seven other nations, including China, India, and Russia, hold invitations dating to 2013. Other countries are classified as participants, which can join in board discussions but not vote. The growing number of participants makes these deliberations increasingly unwieldy.

Increasing the number of countries also taxes PISA’s finances. Countries with participant status pay for the marginal costs of implementing PISA to the PISA Consortium, plus additional monies to cover the administrative costs of the secretariat. This amount is significantly less than the floor contribution paid by member countries and associates because it excludes some assessment development costs, such as those for new domains, the digital platform, validation studies, and translation validation studies. Worse, the costs involved with the psychometric work required to fit such different levels of performance on the same scale to preserve comparability increase not only with the number of countries but also with the increased number of languages and heterogeneity of the social, economic, and educational environment of participating countries.

If the expansion of PISA to 40 more non-member countries is realized, these governance and financial issues will be magnified.

In its 2013 Global Relations Strategy, the governing board articulated a set of criteria that should guide the process by which nations could participate in PISA’s work. Specifically, they cautioned that before new countries join PISA, the board should consider “the extent to which the number of participants is manageable in view of secretariat resources and the implications for its working methods and those of the PISA Governing Board.”

It is time for OECD to examine whether continued global expansion is consistent with this articulated guidance. Fortunately, at its next meeting in April, the PISA Governing Board is expected to discuss the operational implications of increased participation in PISA within the context of updating its 2013 Global Relations Strategy. In the view of the United States, a pause in PISA’s expansion would provide time for further development of testing methodology and governance structures to ensure that the benefits of the expansion are ultimately realized — for member and non-member countries alike.

Mark Schneider is director of the Institute of Education Sciences at the United States Department of Education.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)