Proposed California Ballot Measure Would Give Parents ‘Legal Standing’ to Sue for Better Schools as Right-to-Education Efforts Spread

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Californians could vote next year on whether students should have a constitutional right to a high-quality education, potentially opening the door to litigation from parents dissatisfied with their children’s schools.

The effort to get the measure on the November 2022 ballot is just getting started, but such a statute would give parents “legal standing” before a judge to argue that districts should make better use of education dollars, said initiative spokesman Michael Trujillo, a veteran political strategist.

“Here’s a chance for parents to become effective policymakers on behalf of their children,” said Trujillo, who has long worked for former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, a supporter of the initiative.

The move comes as parents across the country are vocally asserting their rights to influence the education agenda. Parents’ anger over school closures and controversial diversity and equity initiatives was considered a key factor in tipping the Virginia governor’s race in favor of Republican Glenn Youngkin.

The California initiative would be the third effort nationally to enshrine a child’s opportunity to receive a high-quality education in a state constitution. Supporters have launched similar campaigns in Minnesota and New Mexico.

“Having that right in the constitution could be very helpful in addressing long-standing inequities in our educational system and closing opportunity gaps,” said Ted Lempert, president of Children Now, an Oakland-based advocacy organization. He added that “getting more dollars to kids of color and English learners has to be part of the equation.”

The California initiative, however, includes wording that would prohibit courts from issuing remedies that include “new mandates for taxes or spending.”

That restriction could be an obstacle to improving educational quality, said Jessica Levin, a senior attorney at the Education Law Center, based in New Jersey.

“More funding would be the way to address many of the issues that the proponents of this initiative are purporting to want to fix,” she said. The center represented plaintiffs in Abbott v. Burke, a 1998 New Jersey school finance case that led to far-reaching reforms, including universal preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds.

A recent report from the center gives California a C for the level of per-student funding schools receive from state and local sources. But it grades the state a D on how much it spends on education as a percentage of overall economic activity — less than 3 percent.

State constitutions, Levin added, all include some “affirmative obligation” to provide students a public education, but courts have varied in how they interpret what that education should include.

Federal courts in recent years have also been asked to consider whether the U.S. Constitution should entitle children to an education. Last year, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer agreed to a $100 million settlement in a 6th Circuit Court of Appeals case in which seven Detroit students argued their schools had failed to teach them to read.

On Nov. 1, the 1st Circuit Court of Appeals heard oral arguments in a case in which 14 Rhode Island students argue their schools don’t provide civics education, leaving them unprepared to exercise their rights as citizens.

‘There’s no remedy’

In California, David Welch, who waged a lengthy legal battle challenging state laws on teacher tenure and seniority, is behind the ballot initiative. That lawsuit, Vergara v. California, argued such provisions keep poor and minority students from having effective teachers. In 2016, the California Court of Appeals ultimately held that the attorneys for the nine student plaintiffs were unable to prove that state law controlled teacher assignments.

The state’s powerful teachers unions came out on top when the state supreme court declined to review the case. A ballot measure that aims to improve schools by making it easier to fire ineffective teachers would be certain to reopen that fight. Levin said the initiative “on its face” might sound appealing, but could be a way to once again go after teacher tenure and laws that result in new teachers being the first to go when budgets are cut.

Trujillo said the initiative is not just an effort to revive Vergara.

“What Vergara taught us is that there is a right to a free education,” he said, “but if you want to sue because of a reading gap, there’s no remedy.”

Some experts say the measure, which would need roughly a million signatures by June to qualify, is vague and ignores the limitations districts face when the majority of their budgets are spent on salaries. Laura Preston, director of governmental affairs at F3Law, a California firm that handles education cases, said laws that require districts to negotiate budgets with teachers unions can limit flexibility to address students’ needs.

Schools are also facing teacher shortages now and even superintendents are teaching classes — not a time to discuss getting rid of teachers, she said.

The initiative is “so broad that we’re all trying to figure out what it means,” Preston said, calling the proponents “a bunch of people who don’t know how education works trying to reform education.”

‘A battle royale’

The effort to add the constitutional amendment isn’t the only California initiative likely to provoke a fight with the teachers unions. A venture capitalist is behind a measure to eliminate collective bargaining for public sector employees. The proposal argues that unions “protect bad employees.”

A similar effort failed in 2012, but the prolonged school closures could have shifted some voters’ attitudes. Julia Koppich, an independent San Francisco-based researcher, said proponents could play on “unions being blamed for keeping schools closed longer than some parents thought they needed to be.”

Republicans tried to use parent frustration with school closings during the September election to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom, but were unsuccessful.

“I’m not sure if that anti-union, pandemic-specific anger is of the lasting variety,” Koppich said, but even so, “if this initiative is on the ballot, it will be a battle royale and an expensive one.”

Lisa Gardiner, a spokeswoman for the California Teachers Association said members “certainly believe that all students deserve a high-quality public education,” but that the union does “not take positions on — or even consider — ballot measures until they have qualified for the ballot.”

School closures are also fueling efforts to get two private school choice initiatives on the ballot. Now in the signature-gathering phase, both would create education savings accounts, of either $13,000 or $14,000 per year, that families could use for private and religious school tuition.

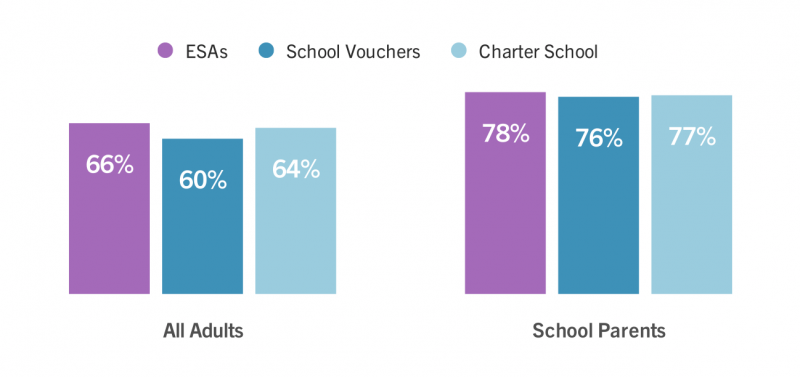

“The pandemic required families to try alternatives,” according to one proposal. “Today more than 60 percent of families are interested in alternative learning options for their students beyond the traditional public school system.”

State officials estimate the cost of the program would range from $4 billion to $7 billion, which “could be paid with reductions to funding for public schools and/or reductions to other programs in the state budget.”

The unions are also likely to oppose efforts to expand school choice in the state. Trujillo said he’s expecting a “well-funded” campaign to defeat the constitutional amendment guaranteeing a high-quality education if it goes before the voters. But he’s hoping that when proponents highlight smaller class sizes and higher pay for qualified teachers as possible results of the amendment, the unions might like what they hear.

“Unions that want to oppose this are going to feel like they’re in upside-down land,” he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)