Pre-K, School Choice Provisions Almost Derailed Final ESSA Deal, Authors Reveal on Law’s Fourth Anniversary

Washington, D.C.

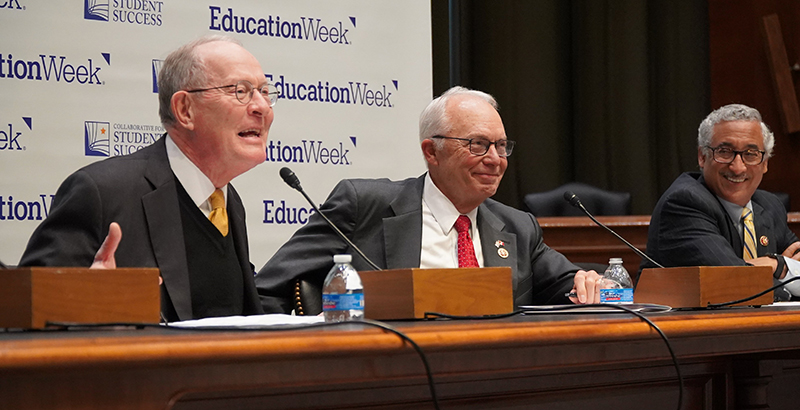

Though widely sought as a vehicle to reform federal K-12 policy, the bill that became the Every Student Succeeds Act was nearly derailed by concerns over preschool, the law’s chief authors said Tuesday.

Sen. Patty Murray, a former pre-K teacher and longtime advocate for early learning, wanted to include new federal preschool programs in the bill. That was anathema to Republicans, long skeptical of adding new federal programs for young children — but Democratic support was needed to pass the bill out of the Senate.

“We just came to a halt over that issue,” Sen. Lamar Alexander, chairman of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, said at the event celebrating the law’s four-year anniversary.

Other panels at the afternoon-long event, sponsored by the Collaborative for Student Success and Education Week, focused on school improvement, testing, military-connected students and new per-pupil spending disclosure requirements. Much of the conversation focused on the long-standing inherent tension in the law, between state control over education and civil rights guardrails meant to protect long-marginalized students; civil rights advocates say the uneven implementation has meant inadequate efforts in some states.

Former representative John Kline, then chairman of the House Education and the Workforce Committee, recalled he was under instructions from then-Speaker Paul Ryan to craft a bill that could win “the majority of the majority” — that is, most Republicans.

More money for pre-K was doable, but a new program within the Department of Education, itself a longtime punching bag for many conservatives, wasn’t, he said.

Ultimately, Murray and Sen. Johnny Isakson, Republican of Georgia, worked out a deal to authorize Preschool Development Grants designed to help states create or expand pre-K programs. That program, like Head Start, Child Care and Development Block Grants and other federal early learning efforts, is run through the Department of Health and Human Services.

Murray, who spoke later in the afternoon, touted the inclusion of early learning programs in federal K-12 policy for the first time as among the bill’s biggest successes.

“I knew we couldn’t pass a bill to fix No Child Left Behind without truly prioritizing early education, which is critical to the long-term success of students. For me, that was a non-starter,” Murray said through a spokesperson Wednesday.

There were other moments of potential implosion, too, Alexander said.

When Alexander’s HELP Committee marked up the bill in April 2015, then-Sen. Al Franken, Democrat of Minnesota, wanted to offer an amendment to ban discrimination in education on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity, while Alexander wanted to add a voucher program that would allow low-income children to use their share of federal funds at public or private schools of their families’ choosing.

Both probably would’ve had the votes to pass in committee, but likely would have doomed the bill on the Senate floor, Alexander said. So he and Franken waited to offer their amendments to the full chamber. Ultimately, neither was adopted.

“It was that kind of cooperation that I think created the Senate consensus,” Alexander said.

And for Democrats, there were several concerns with House Republicans’ first draft of the bill in early 2015, said Rep. Bobby Scott, then the ranking Democrat on the House Education committee and now its chairman.

Specifically, Democrats worried about weak accountability provisions and the inclusion of Title I portability, an idea that would let federal dollars follow low-income students, thus effectively breaking up districts’ ability to concentrate those funds at their neediest schools. In some versions of the proposal, the money could have been used at private schools as well.

“We maintained a working relationship during that partisan battle, because when it got to conference, we were able to negotiate a much better bill,” Scott said.

Though the law expires this year, there’s little chance the law will be reauthorized quickly during an election season, the congressmen predicted.

Current fraught politics aside, there’s no reason to do it: It isn’t needed, and, in contrast to the atmosphere when Congress wrote the bill to replace No Child Left Behind, there isn’t widespread public pressure for a change, Kline said.

“My own prediction will be you won’t see a reauthorization for years. You just won’t push it,” he said.

And because implementation has taken some time, there’s still relatively little known about whether the law is working and if updates are needed.

“The idea that we can know what needs to be changed right now would be a little optimistic,” Scott said.

Disclosure: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Carnegie Corporation of New York provide financial support to Education Week, the Collaborative for Student Success and The 74.

Bloomberg Philanthropies and Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation provide financial support to the Collaborative for Student Success and The 74.

The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, Walton Family Foundation, and William E. Simon Foundation provide financial support to Education Week and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)