Photo Tour: In Rural Virginia, Unearthing the Forgotten Stories — and Heroes — Behind Brown v. Board

Farmville, Virginia

Dozens gathered Saturday at the Robert Russa Moton Museum, the building that once held the all-black segregated high school by the same name in Farmville, Virginia, to partake in a panel discussion featuring former plaintiffs in the 1954 landmark case Oliver Brown, et al. v. the Board of Education of Topeka (KS), et al., which declared “separate but equal” unconstitutional.

Cheryl Brown Henderson, speaking above, helped organize the event in Farmville as part of a national tour commemorating the 65th anniversary of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling, highlighting the untold stories of the hundreds of plaintiffs whose narratives were lost behind the “et al.” of Brown, et al. Henderson is the younger daughter of the named plaintiff in the case, Oliver Brown, and the founding president of the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence, and Research.

Also on the panel (from left to right behind Brown Henderson) were Cainan Townsend, director of education and public programs for the Moton Museum; Joy Cabarrus Speakes, a Moton High student striker and Brown v. Board plaintiff; Joan Johns Cobbs, a Brown v. Board plaintiff and younger sister of Moton High student strike leader Barbara Rose Johns; and John Stokes, a Moton High School student strike co-leader and Brown v. Board plaintiff.

Brown v. Board as heard by the Supreme Court was a consolidation of five cases — Kansas’s Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Virginia’s Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Delaware’s Belton (Bulah) v. Gebhart, South Carolina’s Briggs v. Elliott and Washington, D.C.’s Bolling v. Sharpe.

Virginia’s Davis v. County School Board was the only one of the five Brown cases that was student-led. But little of that history makes it into textbooks, Brown Henderson said during the panel Saturday.

“We’ll get a student from Virginia wanting to know all about Topeka, and my response is, ‘What about your case?’ And they won’t know that Virginia was a part of Brown v. Board, so it’s supremely frustrating for us,” she said. “We’re doing our students a disservice by not teaching what actually happened.”

Ahead of the event, The 74 interviewed the former student plaintiffs in their Farmville homes and visited key sites with them in largely rural Prince Edward County, some 70 miles west of Richmond in southern Virginia.

Joan Johns Cobbs was 13 on April 23, 1951, the day that her older sister Barbara called a surprise assembly at Moton High School. Fed up with inequitable schooling conditions, Barbara implored her more than 450 classmates to protest for a new school building that had the same resources that the town’s all-white schools had.

The Johns’ home burned to the ground in the 1950s, during a weekend that the family was in Washington, D.C., visiting relatives. While there was no evidence nor conclusion regarding the cause of the fire, the family suspected that it was arson — retaliation from the white community as a response to Barbara’s activism. Shortly before Barbara’s death in 1991, she rallied her siblings to build a new house on the same land. She passed before construction completed. Joan Johns Cobbs and her husband now live in the reconstructed house, pictured above.

Moton High was intended to house 180 students, but its student body grew to more than 450 by 1951. Students who didn’t fit in the main building took lessons in tar paper shacks heated by potbelly stoves, and the school lacked textbooks and facilities like an infirmary and teachers’ restrooms. The school’s auditorium also served as its gymnasium and cafeteria as well as overflow classroom space.

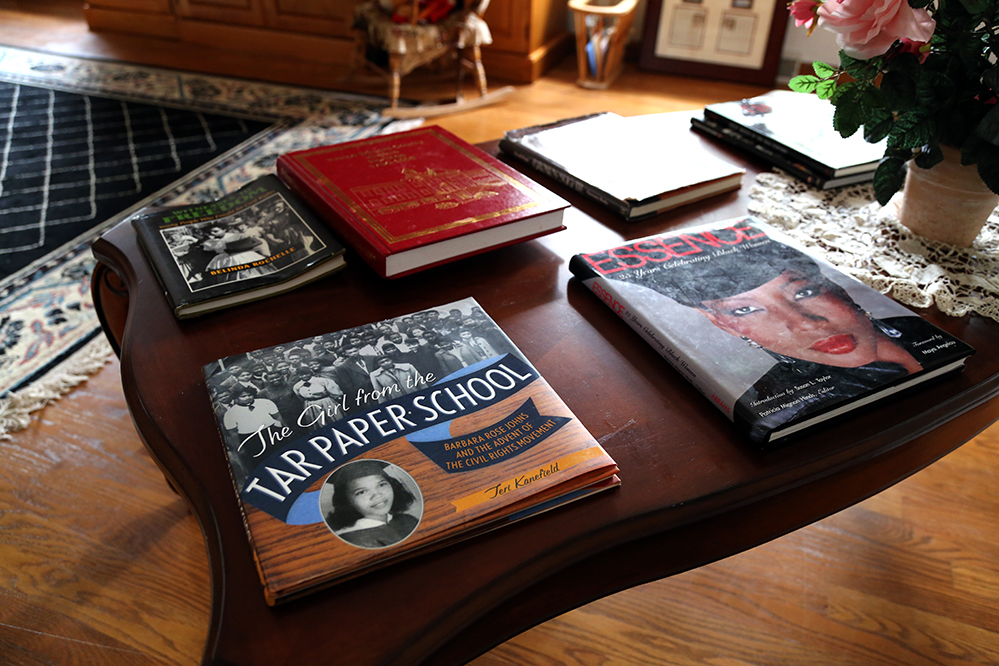

To this day, Joan Johns Cobbs keeps reminders of her sister Barbara’s activism in her living room.

Earlier this year Cobbs wrote about her sister’s activism. Read her reflection here.

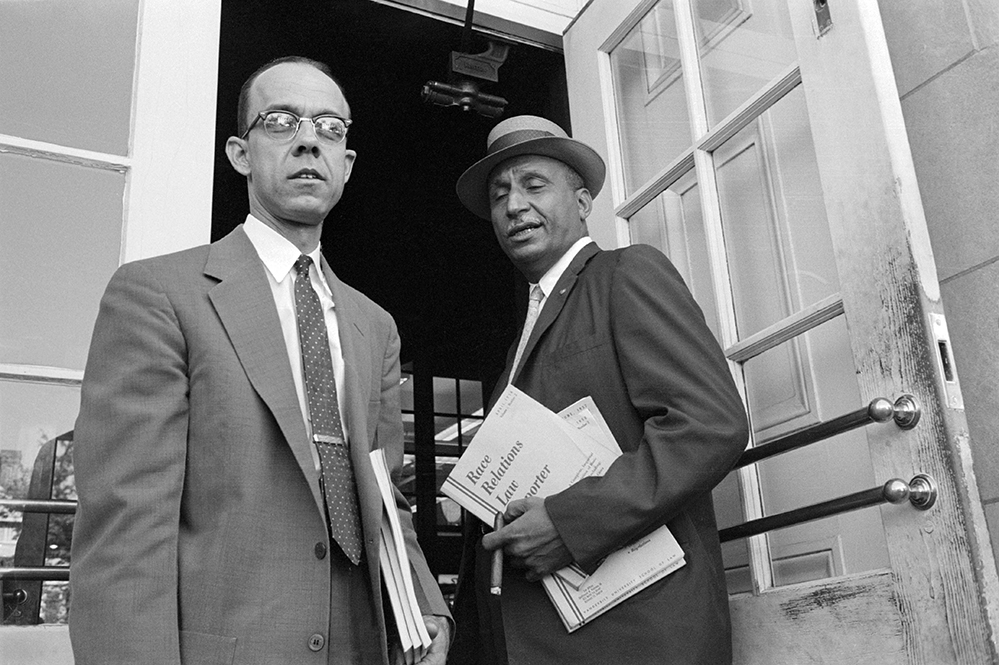

Barbara’s impassioned speech on that April day motivated the student body to stage a walkout that lasted two weeks. That strike led NAACP attorneys Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill (respectively pictured below in 1958) to file Davis v. County School Board on behalf of the students a month later.

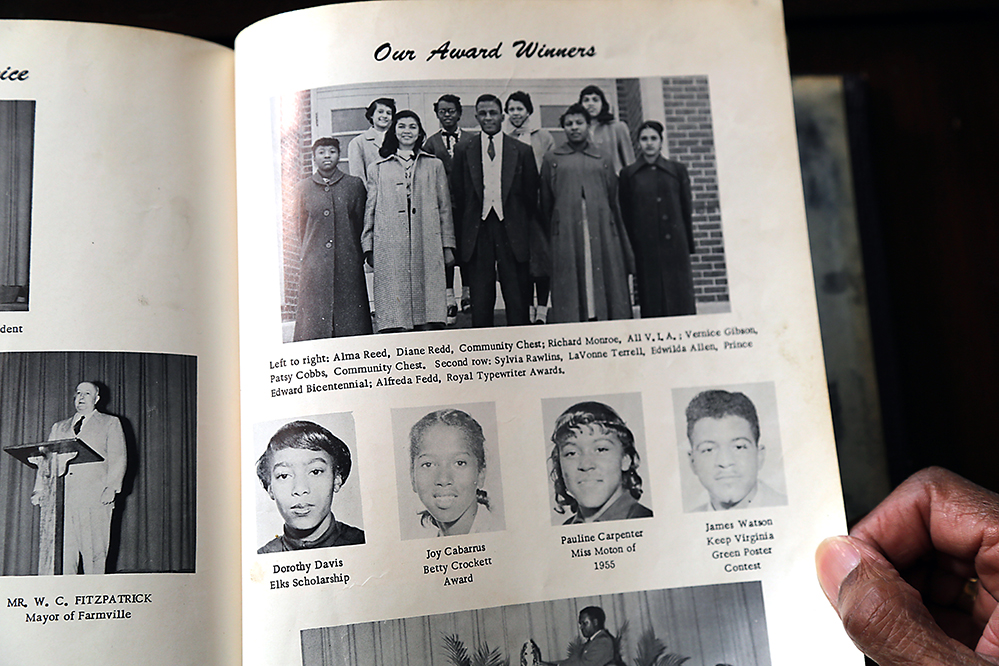

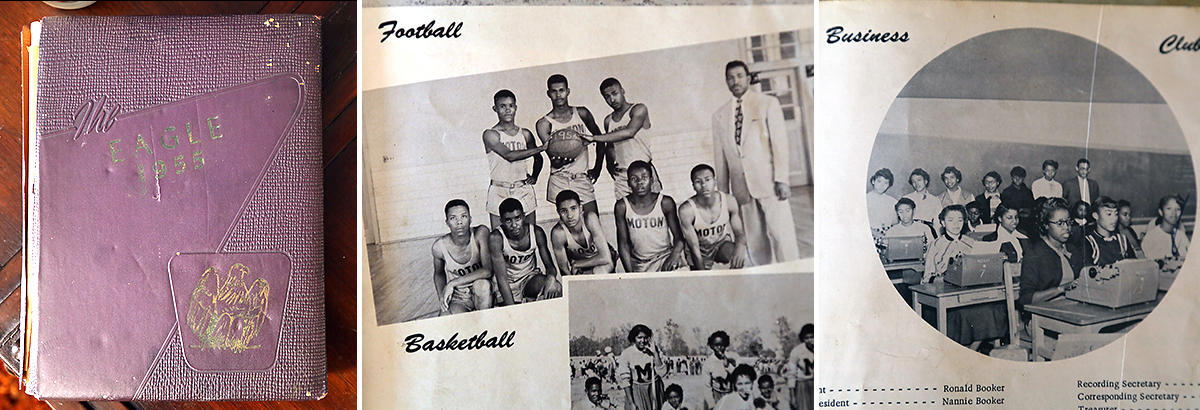

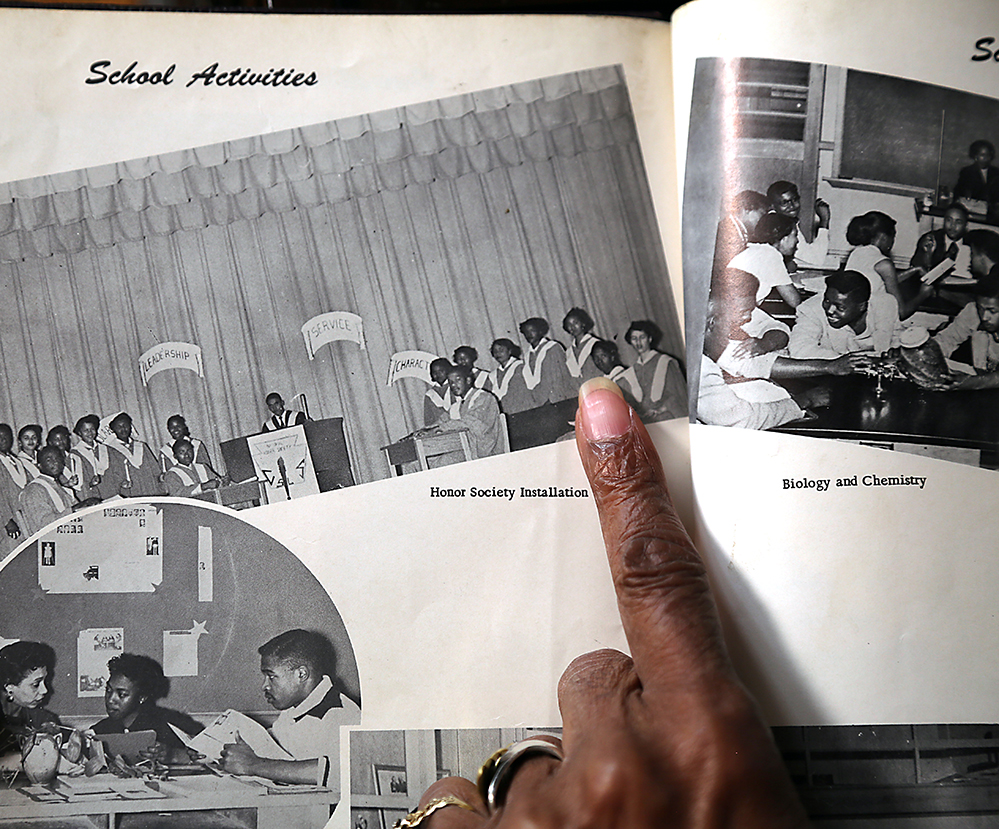

Joy Cabarrus Speakes was one of the hundreds of students who protested and one of the student plaintiffs in Davis v. County School Board — later Brown v. Board. Above, she looks at a Moton yearbook from 1955 (top) and is pictured here on the porch of her current home (bottom) in Farmville, Virginia.

Cabarrus Speakes won the school’s Betty Crocker Award that year for demonstrating excellence in culinary skills. The yearbook mistakenly identifies Betty Crocker as Betty Crockett.

All photos by Emmeline Zhao for The 74 unless otherwise indicated.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)