New Report: School Cops Double Student Arrest Rates and Race, Gender Key Factors

Government watchdog reveals students twice as likely to be arrested when officers are present and their race, gender and disability play pivotal role.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Arrests were two times greater in schools with a regular police presence than at similar campuses without one and race, gender and disability were huge factors in which students were detained, according to a new government watchdog report.

The Government Accountability Office report found that when “race, gender and disability statuses overlap” — a concept often known as intersectionality — students “can experience even greater adverse consequences.”

“Race, gender and disability all figure prominently when it comes to arrests, but they matter differently for different groups of students,” report author Jacqueline Nowicki, the GAO’s director of education, workforce and income security, told The 74.

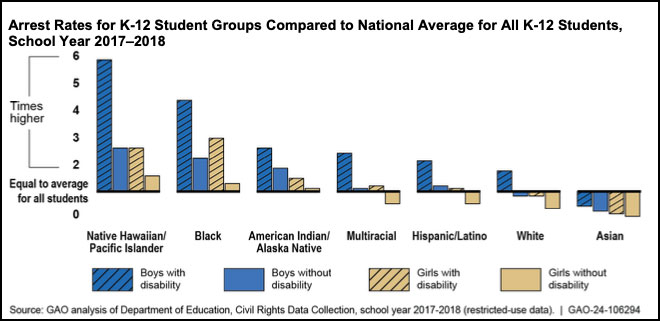

The GAO’s analysis of federal student arrest data found that Black and indigenous students faced school-based arrests at rates two to three times higher than those of their white counterparts. Among demographic groups, the report found, the arrest rate was particularly stark for boys with disabilities.

Students with disabilities are arrested at higher rates than students of the same gender who did not receive special education services, researchers found, however, Black girls without disabilities are arrested at a greater rate than white girls with disabilities.

The GAO report adds the latest insight into the ongoing debate over whether police make schools safer or whether their presence feeds the school-to-prison pipeline, particularly for students of color and those with disabilities. After a Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd in 2020, some school districts cut ties with their local police agencies in the face of student and community protests. But many of them brought cops back after students returned post-pandemic with heightened mental health and behavioral issues.

The report, which was mandated by Congress, found that student arrests were particularly high in schools where police officers engaged in routine student discipline — something that education and law enforcement leaders say is outside the scope of how school-based police should function.

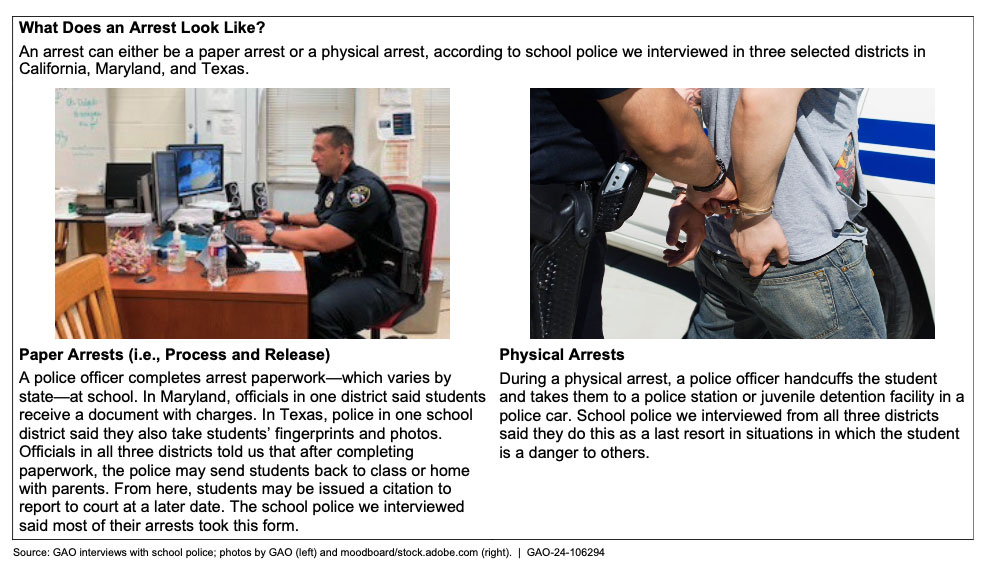

To reach its conclusions, the federal watchdog analyzed recent, pre-pandemic data on student arrests nationally collected by the U.S. Education Department and conducted site visits at three unidentified school districts in California, Maryland and Texas. It was on the site visits that researchers “got a flavor for what it looks like to have police in schools,” Nowicki said. On paper, the officers were not supposed to participate in routine student discipline, like acting out in class, she said, but researchers found that school officials often lacked a clear understanding “of what it means to involve police appropriately.”

“There were districts that explicitly were not supposed to have police involved in discipline but the police were telling us that teachers and administrators were calling them for discipline issues,” she said. “There’s not necessarily a common or a clear understanding all the time about the roles and responsibilities of police in schools, even in districts that have police.”

Mo Canady, executive director of the nonprofit National Association of School Resource Officers, said that while school policing models differ in districts across the country, they’re generally trained to refrain from getting involved in student disciplinary incidents. However, he noted that there are no national rules that specify how officers are trained or selected.

“There are national best practices or recommendations, but there are no required national standards,” said Canady, whose group provides training to school-based officers. “I think this speaks more loudly to the lack of national standards than anything else.”

Research has for years called attention to longstanding racial disparities in student suspensions, expulsions and arrests. In one recent report, researchers found that officers perceived students as more threatening in schools where students of color made up the largest share of enrollment compared to officers who worked at campuses where students were predominantly white.

Among academic researchers, officers’ role in preventing campus crime and violence is an ongoing question. Another paper found that placing school resource officers on campuses led to a marginal decline in some forms of school violence including fights, and a stark uptick in student disciplinary actions, especially among Black students and those with disabilities.

In Chicago, the removal of police officers in some of the city’s high schools beginning in 2020 has shown promising results, according to new University of Chicago research, which found that taking school cops out of the equation “was significantly related to having fewer high-level discipline infractions.”

To the GAO’s Nowicki, the gap in arrest rates is unlikely explained by “the idea that police are just responding to significant behavioral incidents more” often in schools with a regular police presence compared to those without one.

“I am not convinced,” she said, “that the answer is, ‘Well, there’s just more crime in schools with police.’ ”

This is our biweekly briefing on the latest school safety news, vetted by Mark Keierleber. Sign up below.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)