New Data: Despite K-2 Reading Gains, Students Face a ‘Much Harder Journey’ Ahead

Experts say new curriculum, better instruction and tutoring are making a difference, but fall results from Amplify show recovery is slowing.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Young students have made less progress in reading this year than they did earlier in the post-pandemic period, according to new data.

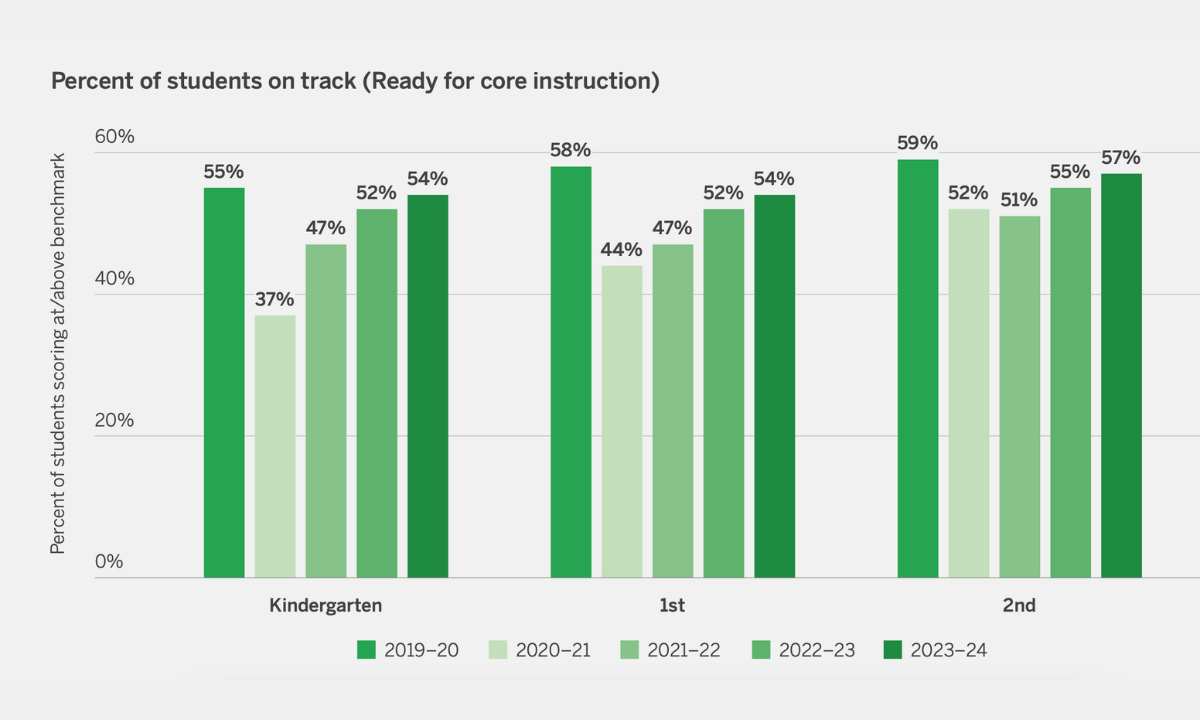

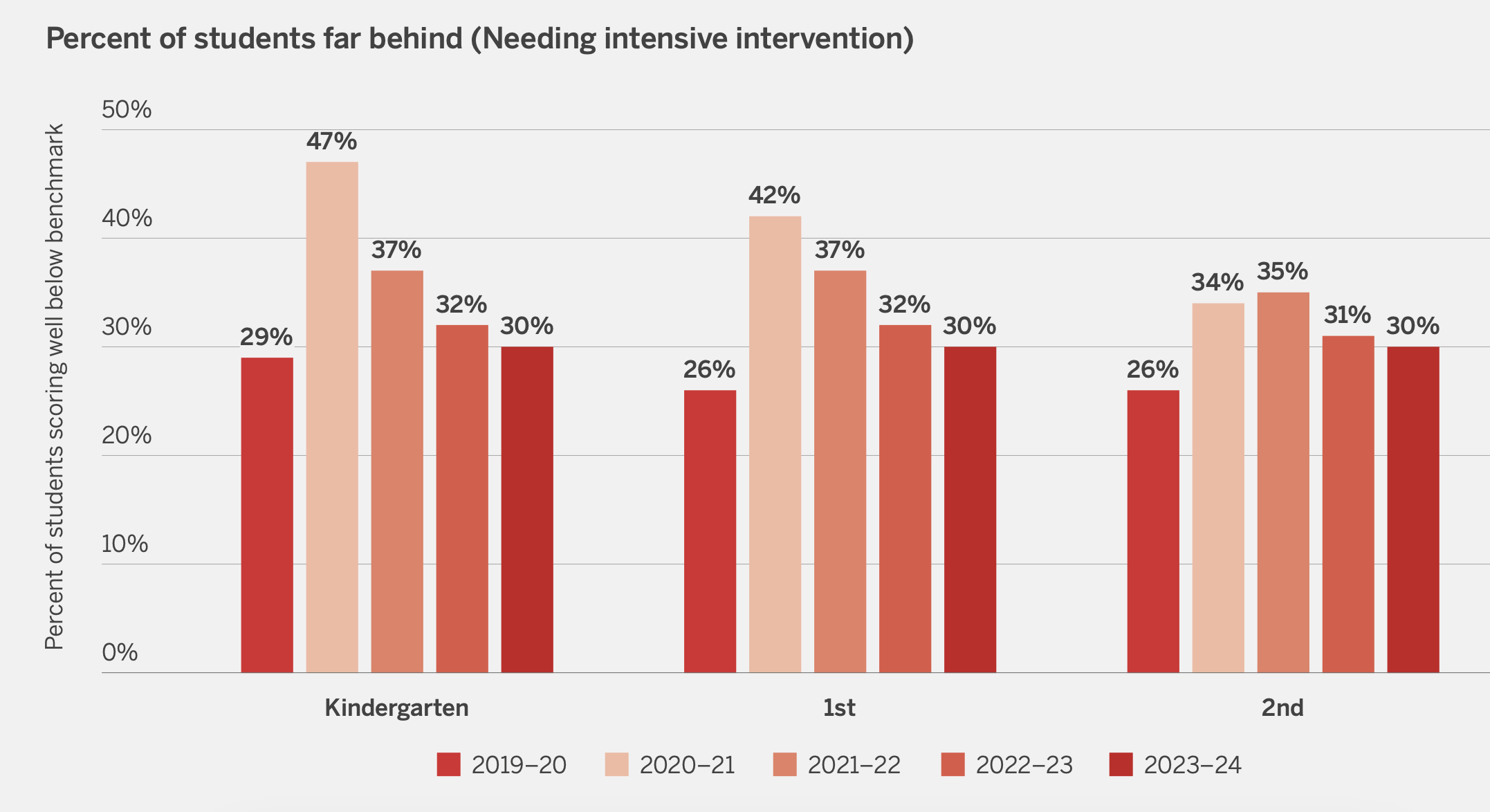

The results from curriculum provider Amplify show that the number of K-2 students on track in literacy increased by 2 percentage points compared to this time last year. The leap between 2021-22 and 2022-23 was more than twice as large — 5 percentage points.

That means students still haven’t reached pre-COVID performance in reading. To Paul Gazzerro, Amplify’s director of data analysis, the latest scores show that while many students have now hit grade-level performance, there’s still tough work ahead to reach those who are severely behind.

“Maybe the lower-hanging fruit has been pulled, and now the much harder journey is there,” he said. “There are a lot of kids who are really struggling and need that intensive support.”

The data from 300,000 students across 43 states is the latest indicator that the billions of dollars spent on stronger curriculum materials, teacher training and tutoring over the past three years has paid off. That’s especially true for Black and Hispanic students, who were disproportionately affected by the pandemic. The results, from a widely used assessment called Dynamic Indicators of Basic Literacy Skills, or DIBELS, show that those students made greater gains than white and Asian students over the past two years.

“That’s exactly what we want to see,” Gazzerro said. But he added, “In this last year, everything slowed down. It’s also slowing down for those subgroups.”

The report recommends schools universally screen students for reading difficulties like dyslexia, assign staff to spend extra time with students who haven’t mastered foundational skills and ensure all teachers get training in research-backed methods.

‘Additional headwinds’

The Amplify results resonate with Todd Collins, a school board member and literacy advocate in Palo Alto, California.

Students who started school after the end of remote instruction clearly made more progress than those who learned to read over Zoom or had to rely on worksheets while schools were closed. But schools now face the “additional headwinds” of chronic absenteeism. And while the Biden administration continues to emphasize tutoring and summer school for students learning well below grade level, those efforts can’t replace strong basic instruction, he said.

“Band-Aids don’t fix bullet holes,” said Collins, who supports legislation that would move the state to a phonics-based approach. The Amplify data, he said, “really underscores why these bills are so important. Supplementing [instruction] is not going to solve the problem.”

Lawmakers have yet to take action on the bill. If it passes, it would bring the state — whose leaders have been reluctant to mandate a single approach to reading instruction — in line with the more than 40 states that have enacted so-called science of reading laws.

The legislation has some strong opponents, including advocates for English learners, who say they worry teachers might eliminate strategies that can still help students learning English, such ase using pictures to understand words. As in other states, the legislation would phase out techniques that encourage students to rely on visual cues to guess words.

The California Teachers Association has not yet taken a position on the bill, but previously opposed universal screening, which uses short assessments to see if students are on track. They said the practice can lead to overidentifying students for special education and takes up too much class time. Even so, the state last year joined 40 others that require it.

A state panel is currently preparing a list of approved screeners. Teachers already trained in the science of reading, however, aren’t waiting, said Leslie Zoroya, a reading and language arts coordinator for the Los Angeles County Office of Education. With a $5 million federal grant, the office has trained over 6,000 teachers from across the state over the past three years.

“In the beginning, sometimes people are like, ‘Now wait, what?’ I’ve been teaching reading for 20 years. Is this a pendulum swing?’ ” she said. “It’s not a pendulum swing. It’s getting the reading research into the hands of the teachers who need it.”

Ronit Glickman, who teaches kindergarten at a charter school in Santa Rosa, California, is among those who have found screening to be a valuable part of her teaching.

“I know exactly what’s going on with any student at any moment in time, and I can tell the parent in great detail,” she said.

Using a screener from Acadience Learning, she asks students at the beginning of the year to name letters and identify the first letter sound in short words like “cat” or “man.” Naming just four or fewer puts them in the “red” range and means they are scoring well below expectations. When students come back from winter break, she screens them again.

“Most students move to the green,” meaning they’re making the right amount of progress, she said. But she always has a few that miss the mark. By using the screener, she said, “I know to keep my eye on those students.”

The Amplify data shows that the percentage of students needing the most help is dropping closer to 2019-20 levels — especially in kindergarten, where it’s just 1 percentage point higher than before the pandemic. But in first and second grade, the percentage needing “intensive intervention” is still 30%, compared to 26% four years ago.

To Karen Vaites, a literacy and curriculum expert, the finding that student progress has tapered off shows that passing a reading law is just the beginning. Most laws emphasize training and screening, but not choosing a strong curriculum, she said. She pointed to Tennessee as a model for training teachers and “getting high-quality curricula into the average district.”

“The real lesson of this moment for the science of reading is that training of teachers alone is not enough,” she said. “You’ve got to give teachers the tools. States have to get all these pillars right if we want to see student outcomes.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)