Post-Pandemic, 2 Out of 3 Students Attend Schools With High Chronic Absenteeism

Analysis of federal data reveals ‘a relaxed attitude’ toward daily attendance, experts said.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

It’s well established that chronic absenteeism has skyrocketed since the pandemic. But a new analysis of federal data shows the problem may be worse than previously understood.

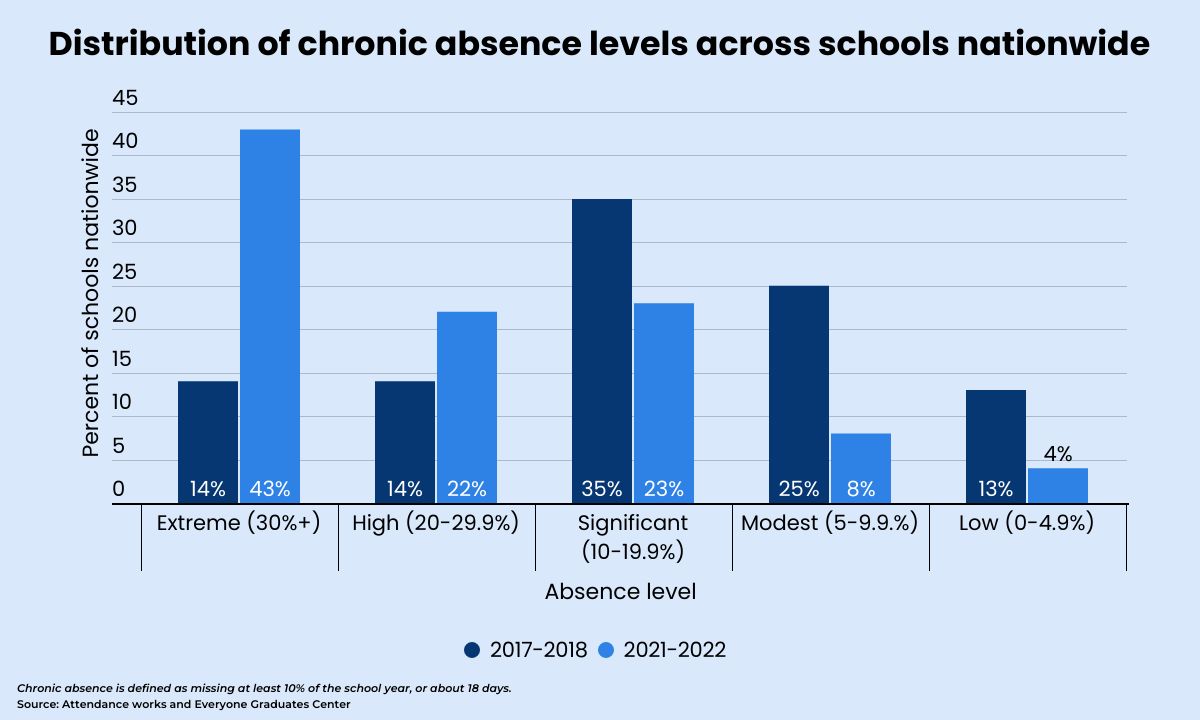

Two out of three students were enrolled in schools with high or extreme rates of chronic absenteeism during the 2021-22 school year — more than double the rate in 2017-18, the report found. Students who miss at least 10% of the school year, or roughly 18 days, are considered chronically absent.

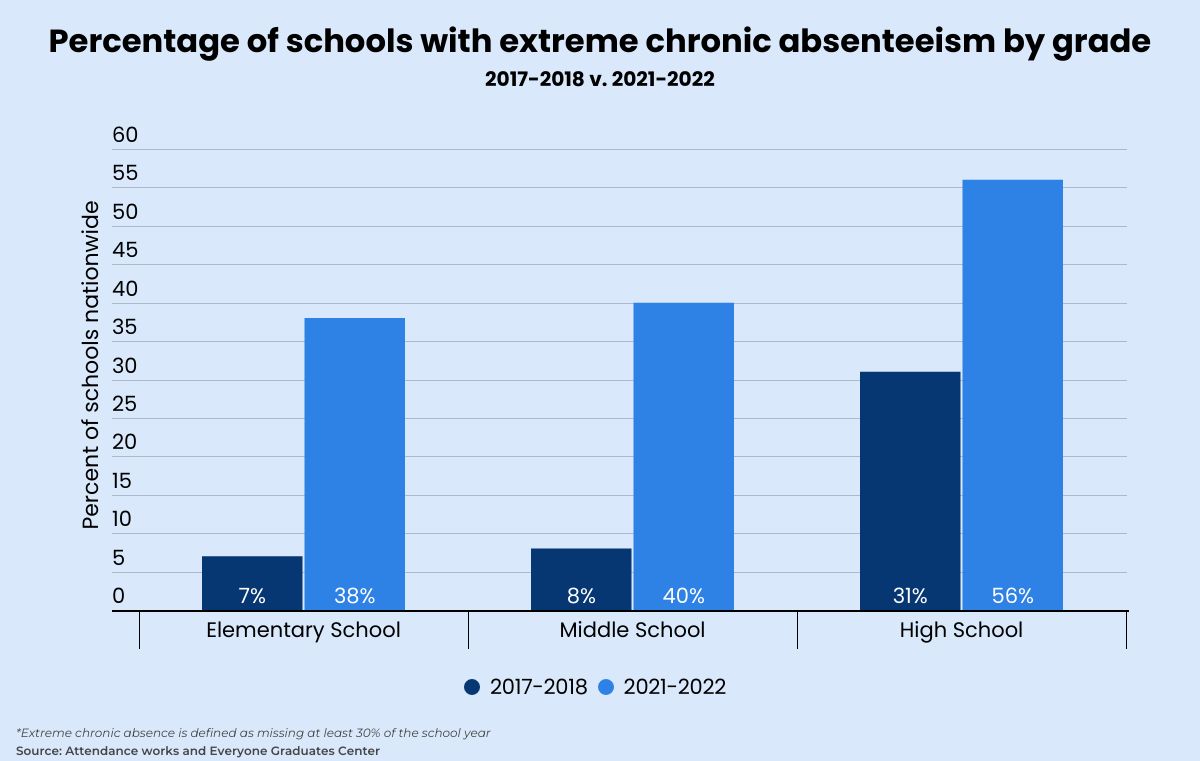

The analysis, from Attendance Works and the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University, shows a fivefold increase in the percentage of elementary and middle schools with extreme rates, where at least 30% of students are chronically absent.

In addition, the researchers released an early look at 2022-23 figures from 11 states. The data shows that overall chronic absenteeism levels remain extremely high at 28% — well above the pre-pandemic level of 16%.

Empty desks have a negative impact on both teachers and students who are still trying to make up for lost learning during the pandemic, said Hedy Chang, founder and executive director of Attendance Works.

“It makes teaching and learning much harder,” she said. She finds the increase at the elementary level especially alarming because absenteeism becomes “habit forming.”

Many students started preschool and kindergarten remotely during the early years of COVID and missed out on a normal transition into school. “When they start off not ever having a routine of attendance, what does that mean for addressing it in middle and high school?” she asked.

The analysis — the first of three researchers plan to release on the federal data — shows that the percentage of high schools with extreme rates increased from 31% to 56% during that time period. A November release will focus on demographic disparities and one in January will examine state-level trends.

Soaring absenteeism rates have contributed to declines in math and reading scores on national tests, the White House said last month. Despite billions available to schools to address learning loss, students can’t take advantage of extra help if they’re not in school. Districts are tackling the problem by dedicating staff to attendance, offering home visits with families and targeting voicemail messages to alert parents that their children’s absences are piling up. Experts say it takes multiple strategies to make a dent in what might seem an insurmountable challenge.

“If we aren’t careful, the problem can feel overwhelming,” said Terri Clark, literacy director at Read On Arizona. The nonprofit began efforts to improve attendance seven years ago when research showed that reading performance declined as chronic absenteeism increased. But when schools tailor their strategies to students’ needs, they can make progress, Clark said.

“Often the focus is on awareness and getting the word out,” she said. “But you can’t stop there. What if a family can’t get [to school] everyday?”

Her organization is working with about 60 districts across the state to better identify the barriers that keep students from attending school regularly. One is the Tanque Verde Unified School District, near Tucson, where chronic absenteeism has more than doubled to 27% since 2018. Superintendent Scott Hagerman pointed to a practice that he hopes will bring the rate back down.

When students are absent, teachers are required to make sure they get their assignments. He knows from experience how important that connection can be to a student.

“When I was a kid, I had a chronic health issue, and the back and forth, in and out of school, without any idea of what was happening when I was gone made coming back harder,” he said. “We are trying to deal with that issue — absences causing more absences.”

Health- and transportation-related issues contributed to high absenteeism before the pandemic, Chang said. But now a school bus driver shortage has further complicated daily commutes. And in focus groups, she’s heard from kindergarten parents who are confused about when they can send children back to school after a fever or illness.

“These are lingering effects of COVID protocols that aren’t helpful,” she said. She stressed the need for frequent, two-way communication between parents and school staff and the importance of reversing a “more-relaxed attitude” about attendance that has permeated school culture.

The risk of ‘wasting precious time’

Sometimes a robocall from an NFL player emphasizing the importance of daily attendance is the added boost a student needs. That’s one of the methods an Ohio district used as part of the Cleveland Browns Foundation’s Stay in the Game initiative.

“If you want to make your dreams become a reality, whether that’s getting into college, getting a good job or even becoming a champion on the playing field, it all starts with hard work,” said cornerback Greg Newsome II, one of three players to record the same message.

The East Cleveland City Schools found that the player’s messages caused a 1.6% decrease in absenteeism among students who had missed school within the previous two weeks. That’s on top of a 6.3% reduction in absences after families received an automated message from a district staff member.

The experiment was part of a Harvard University effort to help schools find the right combination of strategies to address absenteeism.

“How do we layer in the right supports, at the right intensity, for the right students, at the right time?” asked Amber Humm Patnode, interim director of Proving Ground, a project of Harvard’s Center for Education Policy Research. The team works with districts to test solutions before scaling them districtwide. Without gathering evidence on what works, Patnode said, “we risk wasting precious time, resources and energy on things that may not result in actual reduced absences.”

The Euclid City School District has also participated in Stay in the Game. One kindergartner last year received three tickets to a Browns game after making significant progress in attendance. Six-year-old Mekhi Bridges had a speech delay, which made his mother Tasia Letlow extra cautious about getting him to school everyday.

“I wasn’t comfortable with him riding the bus because of not being able to necessarily communicate everything,” Letlow said. But she also had car trouble, and it wasn’t long before Mekhi amassed over 20 absences. The district sent a letter alerting her to the problem.

Targeted letters are just one way the district has addressed a chronic absence rate that reached 73% in 2021. This fall, Jerimie Acree, attendance and residency coordinator for the district, is trying a different approach for middle and high school students who miss class — a deterrent he calls “working lunch.” Students who cut three times have to spend lunch in the media center away from their friends and without their phones.

“It is totally in place to inconvenience them,” Acree said.

The district’s attendance clerks — staff members who are supposed to focus on improving attendance — now report to him. Previously, they reported to principals, where they frequently got sidetracked with other duties.

“[Administrators] would pull that person to do supervision of field trips” among other things, he said. “Attendance work wasn’t being done everyday.”

To respond to the absenteeism crisis, districts and nonprofits across the country have tapped federal relief funds for dedicated positions or to pay educators stipends for home visits. With the deadline to use those funds coming up next year, the ability of districts to sustain those efforts has become “a huge question,” Chang said.

Gina Martinez-Keddy, executive director of Parent Teacher Home Visits — which began in Sacramento 25 years ago — said she’s talking to districts about how to use other sources of federal funding, like Title I, to support the efforts. Research shows the model can have what she called “spillover effects” on chronic absenteeism even if the original intention was to build trust with families.

“Relationship-building works,” Chang said. “That was proven before the pandemic. One-on-one engagement is really essential.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)