In Search of Equity, a Divided Georgia District Taps COVID Funds for Reading Overhaul

Officials in metro-Atlanta area Fulton County hope a $90 million bet on the “science of reading” pays off

By Linda Jacobson | April 27, 2023College Park, Georgia

As an elementary school teacher in Fulton County, Amy Long was used to scarcity. When she prepared reading lessons, she often found herself scrounging through a closet for workbooks only to find there weren’t enough for every student. She compiled websites where she and her colleagues could download free phonics “readers” because the school lacked a complete curriculum.

“It’s really frustrating when you have something, but you don’t have all of it,” said Long, who taught for eight years at Renaissance Elementary — a predominantly Black, high-poverty school at the south end of the Atlanta-area district. Long, now a literacy coach at another South Fulton school, kept snacks on hand for students who hadn’t eaten breakfast and saw her class roster change regularly as families moved from one rental home to another.

Schools in largely white, well-off North Fulton offered a stark contrast.

Backed by active PTAs and strong community support, many schools stocked full sets of chapter books and computer programs that provided students with extra practice on early literacy skills.

“It was 100% inequitable,” said Long, who has worked in the Fulton County Schools for 12 years. Students didn’t get “the same learning experience as their peers in a more affluent area, simply due to the location of their school.”

Now, officials in Georgia’s fourth-largest district are hoping an infusion of federal relief funds will change all that. Fulton has allocated roughly a third of its $262 million in pandemic aid to replace a patchy and uneven approach to reading with a solid, phonics-based curriculum. The initiative, which includes training teachers and administrators in how children learn to read and adding K-2 literacy coaches in all 60 elementary schools, is an attempt to give students an equal shot at staying on grade level, regardless of where they live.

“The equity issue will always be there,” said Franchesca Warren, a school board member who represents 16 schools in South Fulton. In 2016, she helped launch an advocacy group to better educate parents about the district and pushed for a stronger emphasis on literacy at her own children’s school. “This is literally a marathon. We are changing the opinions and viewpoints of South Fulton schools one parent at a time.”

‘Ask’ instead of ‘aks’

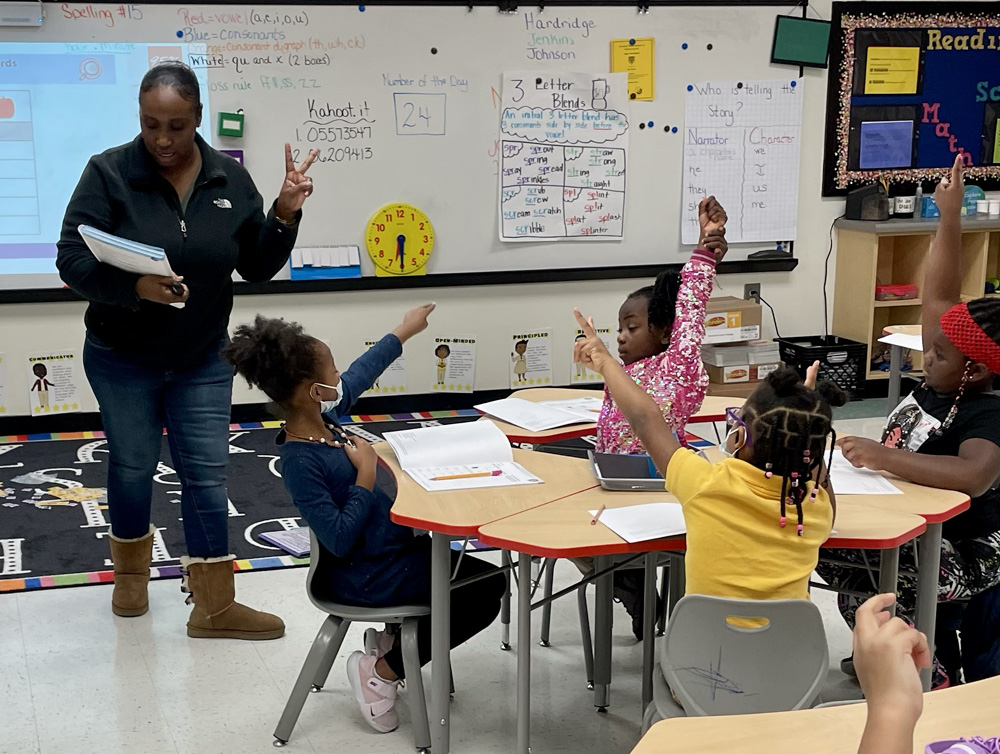

On a rainy Monday, first-grade teacher Sheila Brown read from a lesson handbook as she looked over her students’ shoulders at Stonewall Tell Elementary in College Park. They sorted words with short and long vowel sounds into columns in their workbooks. Shifting their attention to the white board at the front of the room, they pointed two fingers toward the vowels in “make.”

“Remember when you see the silent ‘e’ what happens with the vowel,” Brown reminded them. She asked the name for a word with a short vowel sound that ends with a consonant, like “can” or “mad.”

“Closed syllable!” they responded enthusiastically.

Brown, a former middle school teacher in the Atlanta district, said she’s never taught this way. Before the new program, she wanted to get students reading, but didn’t spend as much time on “the phonetic part of it,” she said. Now she understands, “Just knowing sight words is not teaching our kids.”

Since last year, the 90,000-student district has spent more than $3.5 million on two contracts with Lexia Learning to deliver its intensive “science of reading” training to more than 3,000 teachers, principals and central office administrators. In addition to the new program, each school’s “governance council” — comprised of teachers, parents and community members — has a say in how it spends a pot of money on extra materials, as long as the purchases support the district’s major objectives, like literacy.

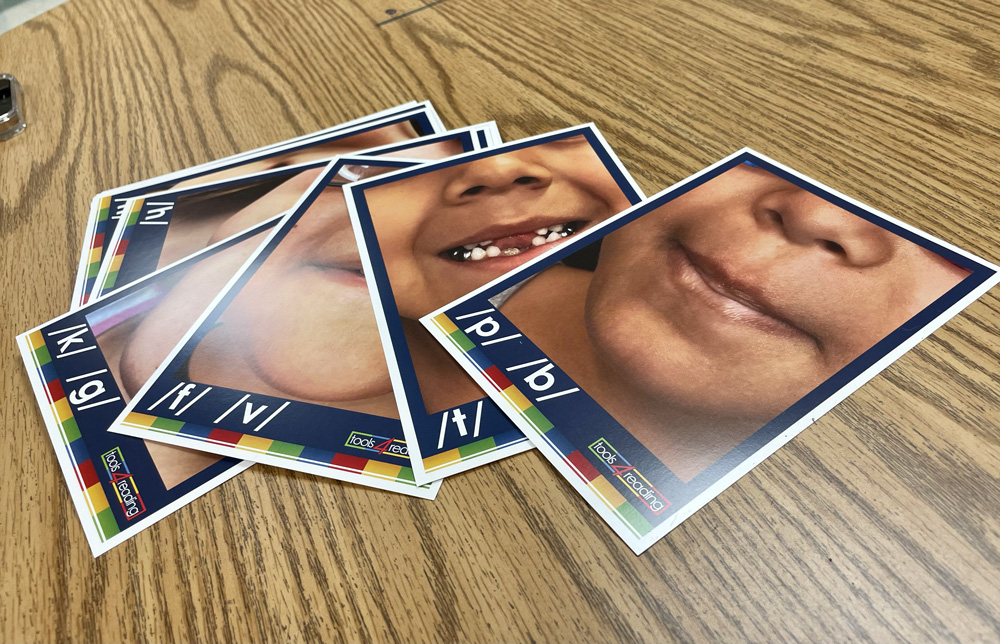

At Stonewall Tell, some of that $46,000 was spent on plastic “phonics phones” that amplify students’ voices so they can hear how they’re sounding out words and “Kids Lips” cards that show how the mouth should look when making those sounds.

A small triumph: Brown said she now hears more students saying “ask” instead of “aks.”

Reforming the district’s reading program began by weeding out less-effective, “whole language” materials in many classrooms. Some schools had been using the Units of Study series from Columbia University’s Lucy Calkins. Reading experts say the program lacks a strong emphasis on phonics.

Over time, literacy instruction in the district had grown to be “a bit of a Wild West,” said Ken Zeff, who served as interim superintendent from 2015 to 2016 and now leads an education nonprofit in the metro region. How a student learned to read and write depended on what schools could afford and was left to local discretion. Long said teachers struggled to share ideas with colleagues across the county because everyone used different materials.

Some parents are beginning to notice a shift — and adjusting their expectations. Courtney Martin said her daughter, a kindergartner at Mountain Park Elementary in the North Fulton city of Roswell, doesn’t recognize as many common words as she thought she would. But she understands that the goal isn’t memorization. The teacher is “building new foundational skills rather than rushing through everything,” she said.

Martin serves on her school’s governance council and helps the literacy coach create classroom “sound walls,” which display the letter sounds in words. The coach, she said, is “taking more off teachers’ plates so they don’t have to worry about that.”

North and south

District leaders are counting on the investment to pay off for years to come. But in a county with one of the largest wealth gaps in the nation, the temporary windfall can only go so far.

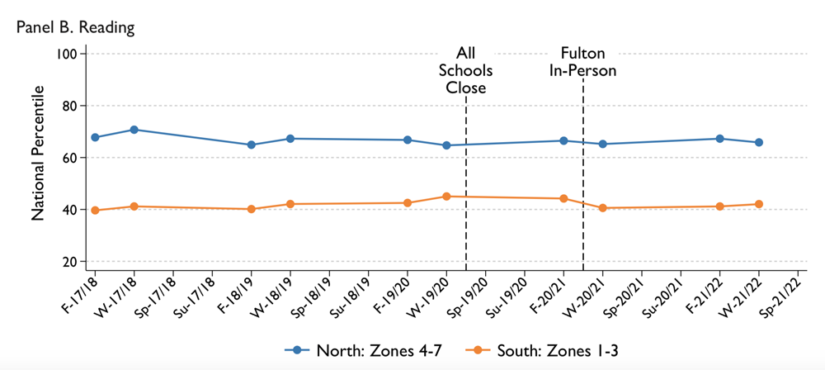

Fulton is geographically split — with the urban Atlanta system sandwiched in between. During the pandemic, long-standing achievement gaps between north and south schools only grew wider.

Last year’s English language arts scores offered a sobering reminder of that gulf.

At one end of the spectrum, just 15% of students scored proficient or higher at Heritage Elementary in College Park, which sits off a main road in the shadow of America’s busiest airport — an area marked by low-income housing, fast food joints and discount stores.

Over 40 miles away at Crabapple Crossing Elementary in Milton, a North Fulton town where two-acre spreads border horse farms and country clubs, the proficiency rate was five times higher.

Research from Georgia State University showed that South Fulton students experienced more learning loss and took longer to bounce back than their peers in the north. The decline leveled off during the 2021-22 school year as the district implemented recovery efforts such as high-dosage tutoring and summer school.

Ericka Thompson, a Black South Fulton mom, understands those disparate realities. In the 1990s, she bussed to a North Fulton high school under a “minority-to-majority” program, which the district phased out about a decade ago. Her two sons attend Westlake High School on the southside, where over 90% of the students are Black and some parents work 70-hour weeks.

The district, she said, did its best to diagnose students’ needs after schools reopened, but “it’s almost like who needs stitches and who needs a Band-Aid,” she said.

Grace Love sees the district’s use of relief funds in her dual roles as parent and district employee. Two years ago, she moved her second-grade daughter from a private school into Stonewall Tell and watched “test scores skyrocket.”

But as a behavior specialist for the district in South Fulton, Love wishes the budget had included more support for grandparents raising children and parents who work two jobs and struggle to help their kids with school. District data shows graduation rates are sometimes 10 percentage points lower than in North Fulton while suspension rates are roughly four to five times higher. Earlier this year, community leaders held a town hall on curbing youth gun violence.

“The dynamics between the north and south are very different when it comes to parental support,” Love said. “There needs to be more attention to the neediest areas if we want to make it equitable.”

But such efforts are complicated by demographic shifts over the past 30 years. The region’s Hispanic population has more than doubled, and many Black residents have migrated from the city limits to the suburbs. That means some of the district’s highest-need schools are in neighborhoods once viewed as more well-off.

“We have parents that live in million dollar houses, and we have children that are homeless,” said Irene Schweiger, executive director of Sandy Springs Education Force, a nonprofit in one of the most diverse cities in the nation. The organization runs afterschool and mentoring programs, and stocks school “mini libraries” with books students can borrow or keep.

Similarly, Warren’s district in South Fulton includes schools where a 100% of students live in poverty as well as subdivisions of stately brick mansions. The route from Atlanta to those neighborhoods takes commuters past Tyler Perry Studios, named for the once-homeless filmmaker turned megastar — a reminder of this Black mecca’s growth into a movie industry hub.

The challenge for leaders has been how to spend the relief money in a way that touches all schools teaching students to read while still targeting those communities with the lowest-performing schools and most complex needs.

Early in the pandemic, the district paid $800,000 to nonprofit Vision to Learn to offer vision screenings and glasses in Title I schools. At Holcomb Bridge School in Alpharetta, for example, over 200 of the school’s 1,000 students needed glasses.

“If a child can’t see, they can’t read,” said Gyimah Whitaker, the district’s deputy chief academic officer, recently tapped to become superintendent in neighboring Decatur. “It’s going to be difficult for them to be able to distinguish a B from a D if it’s blurry.”

They’re also spending about $13.1 million on dropout prevention efforts, which includes the costs of running three student and family engagement centers — two in South Fulton and one in Sandy Springs. The centers offer families free groceries, donated clothes and hygiene items, counseling and referrals to housing assistance.

And the district opened in-school “academies” at the five South Fulton high schools. The smaller, more-sheltered environment — which combines online classes with in-person instruction and counseling — has put graduation back within reach for students thrown far off track by the pandemic.

“I didn’t pass a single math class in all of high school,” said Darryn Williams, who attends Creekside High. “My 10th grade year, we went virtual. That messed me up, completely.”

He spent more time that year helping his five younger siblings get through remote learning than on his own schoolwork. By December of this school year, however, he had earned enough credits in the academy to be a senior and will graduate on time next month.

When the academy opened last fall, teachers began posting small certificates on a bulletin board each time a student passed a course. They soon ran out of space. Now, a dozen rows of the celebratory signs plaster the hallway.

But the district’s biggest bet is on improving literacy, a growing concern as federal money dries up next year. With some educators on staff now certified to offer the course, the district will continue to train future teachers in the science of reading. Whether elementary schools will be able to keep their literacy coaches remains undecided.

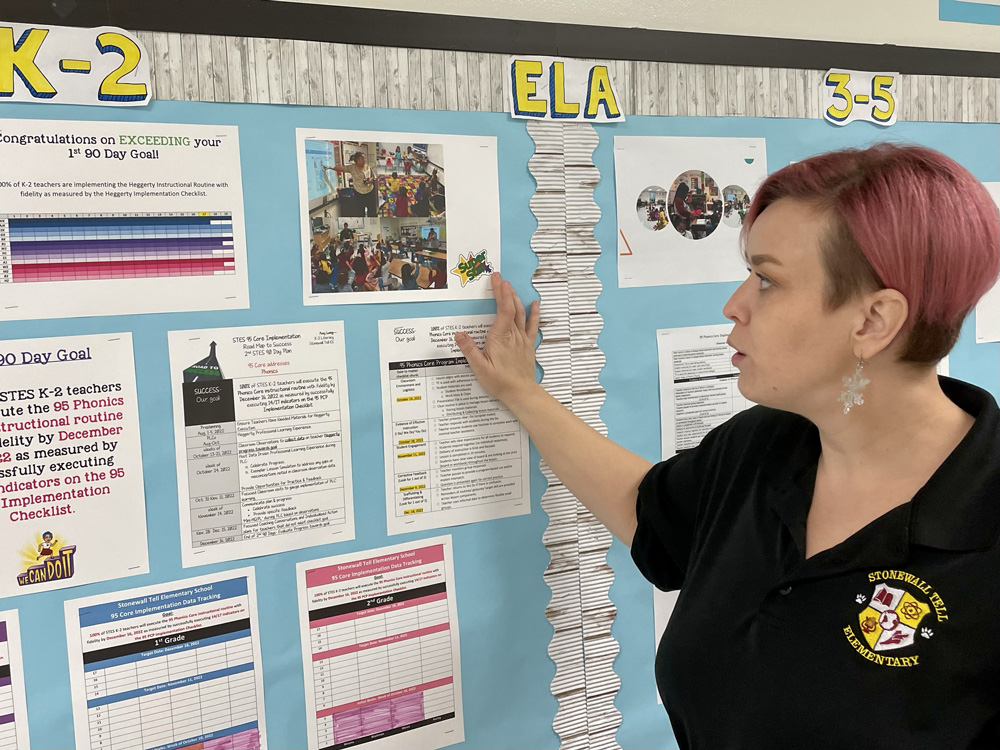

Long, one of those coaches, spends part of her days at Stonewall Tell helping teachers connect the scientific theory they absorbed through hours of training to their more immediate push to get 5-, 6- and 7-year-olds to master phonics and spelling.

She also works directly with small groups of students who were “super, super affected” by the pandemic. Last fall, some second graders, she said, were still learning how to form letters.

South Fulton students who transfer to schools in the north often struggle to keep up with new classmates who are further ahead, Long said. She hopes the new reading program will keep them from getting lost.

“We know better now, so we can do better,” she said. “We need equity for all students, no matter what side of the county they’re on.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter