National Study of 1.8 Million Charter Students Shows Charter Pupils Outperform Peers at Traditional Public Schools

Gains amount to 16 additional days of English and 6 of math a year. But CREDO finds that sector lags in special education and virtual instruction

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Charter school students make more average progress in math and English than their counterparts in traditional public schools, including months of additional learning in some states, according to a new national overview. The authors of the study find that campuses grouped within larger charter management organizations are particularly effective at accelerating student achievement.

The report, released Tuesday morning by Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes, provides perhaps the most thorough perspective available of the landscape of charter schooling, which has grown significantly in recent years.

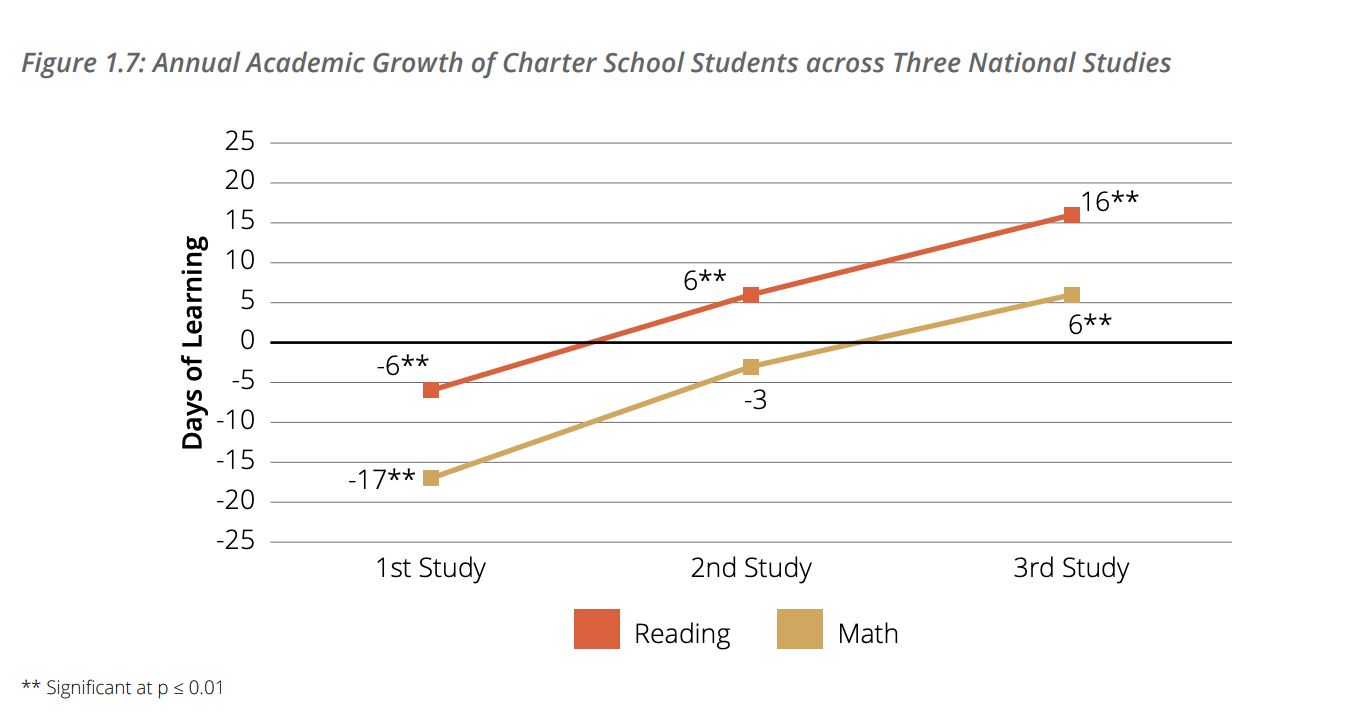

Macke Raymond, CREDO’s founder and director, said that the report sketched a picture of continuous improvement for the charter sector over the last 15 years. The center’s first national analysis, issued in 2009, showed charters under-performing traditional schools in both core subjects; in a 2013 follow-up, they slightly bested traditional schools in English while still lagging in math. That movement represents a modest silver lining for American education, she said, after a prolonged period during which learning — as measured by standardized tests like the National Assessment of Educational Progress — largely stagnated even before the pandemic.

“When you compare [our findings with] the results of NAEP — which, over an equivalent period, have completely flatlined — what you’re looking at is really the only story in U.S. education policy where we’ve been able to create a set of conditions such that schools actually do get better,” Raymond argued.

The new study focuses on charter school performance in 29 states, as well as Washington, D.C., and New York City, incorporating standardized test scores between 2015 and 2019. All told, over 80 percent of tested public school students were included in CREDO’s data set. More than 1.8 million charter students were each paired with a “virtual twin” (i.e., a nearby pupil possessing similar demographic traits and prior test scores) enrolled at the district school that the charter student otherwise would have attended.

The research team calculated that charter school students gained the equivalent of an additional 16 days of learning (based on a traditional 180-day school calendar) in English compared with similar kids at district schools. Their six-day edge in math was smaller, though still considered statistically significant.

But even those averages, comprising millions of student measurements across the country, contain significant variation. Black students attending charter schools gained 35 days of growth in reading and 29 days in math — as if they’d attended school for an extra 1.5 months over a single school year. Hispanics enjoyed 30 extra days of reading and 19 in math. By comparison, white and multiracial students lost the equivalent 24 days of annual math learning in charter schools.

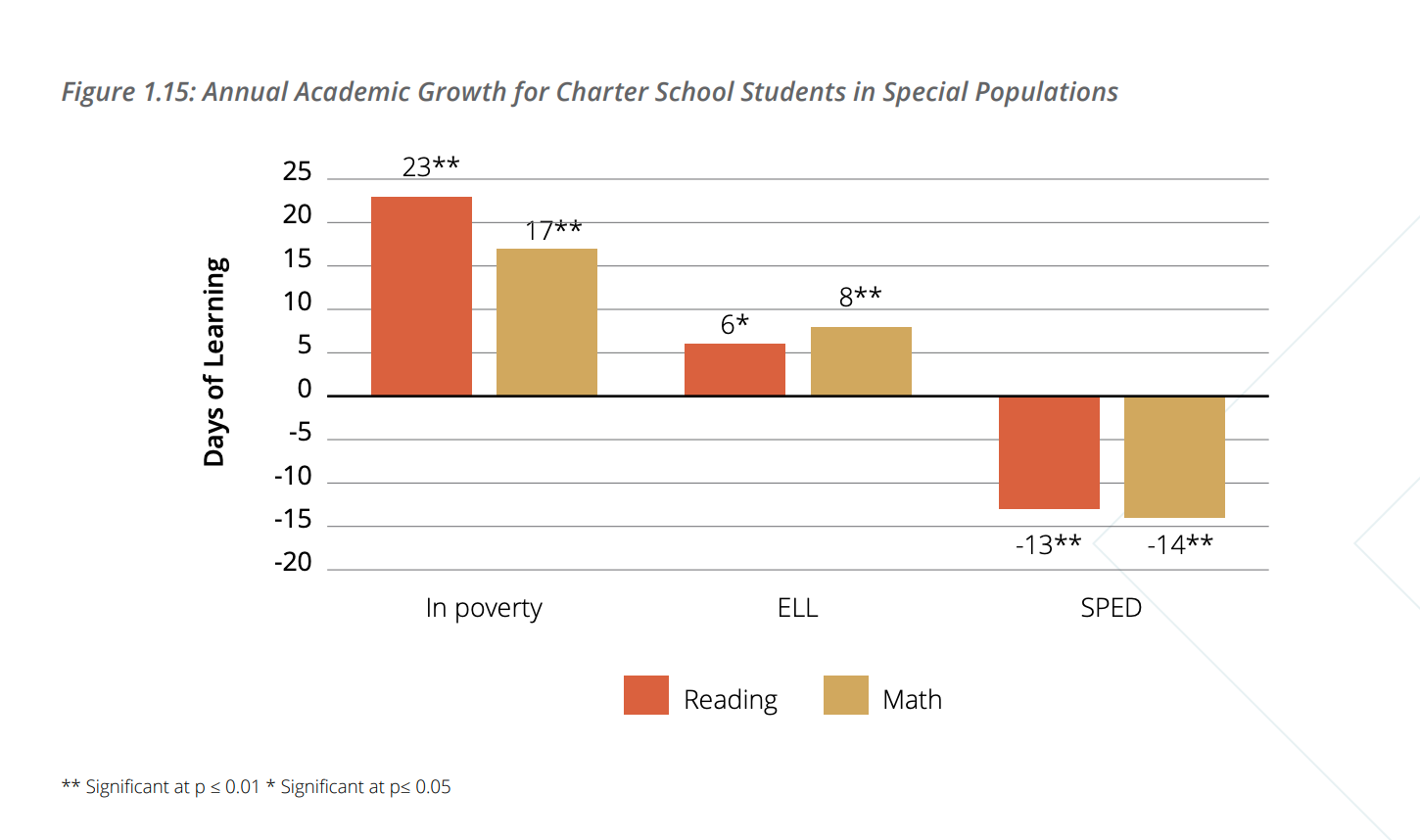

Smaller sub-groups experienced similar divergences. Poor students saw much higher gains in charters than in traditional public schools (23 extra days of reading growth, 17 extra days in math), as did English learners (six extra days of reading, eight in math); students with overlapping designations (such as both African American and low-income, or both Hispanic and English learner), also made considerable strides

By contrast, special education students were seriously stymied, losing 13 days of reading growth and 14 days of math at charter schools relative to kids receiving special education outside of charters. Raymond called that inequity one of the few sore spots revealed by the study, adding that charter schools should be “taken to task” for the collective failure.

“With the exception of very few charter schools that specialize in particular kinds of special education, the sector has basically thrown up their hands and said, ‘This isn’t our job,’” she said.

Even among charters, some types tend to yield better results than others. Specifically, those grouped within a charter management organization (CMO) — a network, either non- or for-profit, that operates multiple schools, such as the well-known KIPP or Success Academy organizations — provide 27 extra days of instruction in reading, and 23 extra days in math, than traditional schools. Stand-alone charters, which encompass roughly two-thirds of all charter schools, generate 10 extra days of reading growth and negative-three days of growth in math.

Douglas Harris, an economics professor at Tulane University who has previously studied the impact of charter schools on surrounding public school districts, said that the results of the CREDO report largely dovetailed with those of his own research on school choice in New Orleans and elsewhere. He also said that the especially impressive findings from CMO-affiliated schools were somewhat predictable given that many cities and states only consider top-performing charter schools as candidates for replication.

“Some of this is kind of mechanical — not in a bad way, it’s just how the sector operates. If you’re a stand-alone, and you do well, you can open another school,” Harris said. “Then you become a CMO, and they’re better because they were selected to build on their own success. That’s a positive aspect of the charter model.”

Even more distinctive was the dividing line between what might be deemed “traditional” charters and those offering instruction virtually, which had already earned an ugly reputation for low academic quality even before the pandemic began. The popularity of the virtual charter sector has grown substantially since the emergence of COVID — one analysis by the Network for Public Education found that fully or mostly online programs enrolled 13 percent of all charter students during the 2020–21 school year — even as they delivered a staggering 124 fewer days of math growth than traditional public schools, along with 58 fewer days of growth in English.

If virtual initiatives were excluded from the national sample, the average charter school advantage would jump from 16 extra days of reading instruction to 21, and from 6 extra days of math instruction to 14.

Martin West, the academic dean at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, called the report “easily the most comprehensive analysis of charter school performance to date” and echoed concerns about the performance of virtual charter schools.

“The results continue to raise questions about the regulatory environment for virtual charter schools, whose results drag down the overall performance of the broader sector,” West said. “These schools may provide an essential option for students for whom in-person learning truly isn’t possible, but state policymakers should look carefully at who is attending these schools and how well they are being served.”

An additional state-by-state analysis showed that individual jurisdictions have built particularly effective charter school sectors. Across New York State, charter students receive the equivalent of 75 extra days of growth in reading, and 73 extra days in math, compared with demographically similar students at district schools. Massachusetts (41 extra days in both subjects), Maryland (37 extra days in both subjects), Tennessee (34 extra days of reading and 39 in math), and Rhode Island (90 extra days of reading and 88 in math) offered similarly impressive statewide results. Charter school students only experienced significantly weaker reading growth in one state, Oregon.

An additional lesson came with respect to new charter entrants versus existing options. New schools opened by existing CMOs tended to outpace their district competitors, but also to be out-performed themselves by older schools within their own CMO.

“The new schools that have come in since the second study are strong, but they’re not as strong,” Raymond observed. “So it’s not that new schools are coming in and kicking butt and dragging the sector along with them. It’s that, over this period, individual schools around the country are making incremental changes that lead to this trajectory of upward performance.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)