NAEP Science Scores Down for Fourth-Graders, Flat for Older Students; Are Reading Challenges to Blame?

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

Today’s announcement of science scores from the 2019 round of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) provides more evidence for two ugly trends in the test often referred to as the nation’s report card.

As with other results from the past few years — including assessments in social studies last year and the core subjects of math and English in 2019 — scores for all age groups are either flat or down from 2015, the last time the test was given. And declines in performance are largely driven by students achieving at the lowest levels.

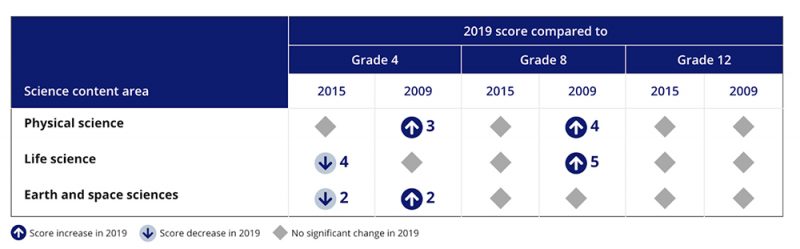

On the 2015 exam, younger students posted general improvements in physical sciences, life sciences, and earth and space sciences. Erika Shugart, executive director of the National Science Teaching Association, told The 74 in an interview that “things looked like they were headed in a positive direction” at that time.

“What we see now is either a leveling off or a decline,” Shugart added. “I can’t speak to what’s going on there, other than it’s not in a good place.”

All told, eighth- and 12th-graders both achieved the same average scores as similarly aged students did in 2015. Fourth-graders saw a three-point drop in average scores, from 154 in 2015 to 151 in 2019. The performance of both fourth- and eighth-graders this year was slightly higher than that of the same age groups in 2009, but high school seniors’ scores stayed the same.

But those averages conceal much wider ranges of variation. In virtually every combination of the three age groups and three science domains, students at the lowest performance levels (i.e., those scoring at the 10th and 25th percentiles) experienced more pronounced downturns. This was particularly true for test takers in the fourth grade: While those scoring in the 50th percentile or above generally held their ground compared with fourth-graders in 2015 — and often performed significantly better than fourth-graders in 2009 — those falling below that benchmark saw decreases of as much as six and eight points compared with 2015.

Officials from the National Center for Education Statistics, the federal agency charged with administering NAEP, said on a call Monday with reporters that the diverging results among children at different performance levels mirrored trends seen both on recent NAEP releases and other assessments, such as the international PISA exam.

While cautioning that the phenomenon was under ongoing study, and offering no empirical argument, NCES Commissioner James Woodworth remarked that success on such tests generally hinges on reading comprehension, and that pervasive literacy struggles among lower-performing students could lie at the root of the stagnant scores.

“Reading is a critical skill that’s needed to improve on all subjects across the board,” Woodworth said. “That is a critical part of this that could be — we’re working on ideas here, but could be — part of the cause of this split we’re seeing across all these subjects and all these different assessments.”

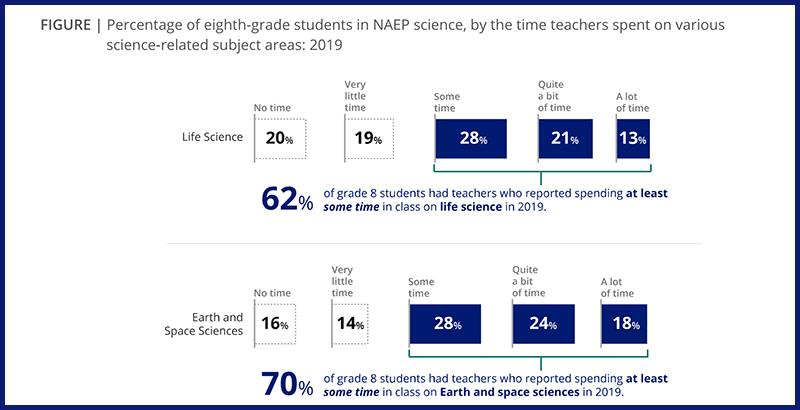

Data gleaned from survey responses provided more fodder for inquiry, as students and teachers gave relatively detailed descriptions of how much class time was devoted to science. In particular, nearly 80 percent of fourth-grade teachers reported that they spent four hours or less on science instruction per week. Thirty-nine percent of eighth-grade teachers said they spent “no time” or “very little time” on life science, while 30 percent said the same for earth and space sciences. Among 12th-graders, 43 percent said they were not presently enrolled in a science course (the same percentage as in 2015, and less than the 47 percent who said the same in 2009).

Recent research has shown that the amount of class time devoted to instruction may play a significant role in how science is taught. A study published last year by University of Vermont professor Tammy Kolbe found that teachers who spent five hours or more each week on science were dramatically more likely to incorporate forms of inquiry-based learning, a pedagogical method that encourages hands-on and collaborative approaches like group activities and discussions of engineering problems. Inquiry-based learning is recommended as a best practice by the Next Generation Science Standards, which were conceived and adopted by dozens of states over the last decade as a way of improving K-12 instruction.

Shugart said her organization advises districts to teach at least five hours of science each week, and that they use approaches like inquiry-based learning. Such practices are necessary to provide “a firm grounding” for students in the elementary grades, she argued.

“A lot of students are not being taught science in that manner. If we aren’t teaching students [for] enough time, and we’re not teaching students in the ways that we know are the best ways for them to learn science, how do we expect these scores to change?” she asked.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)